Sentences

of

Earth & Stone

Sentences

of

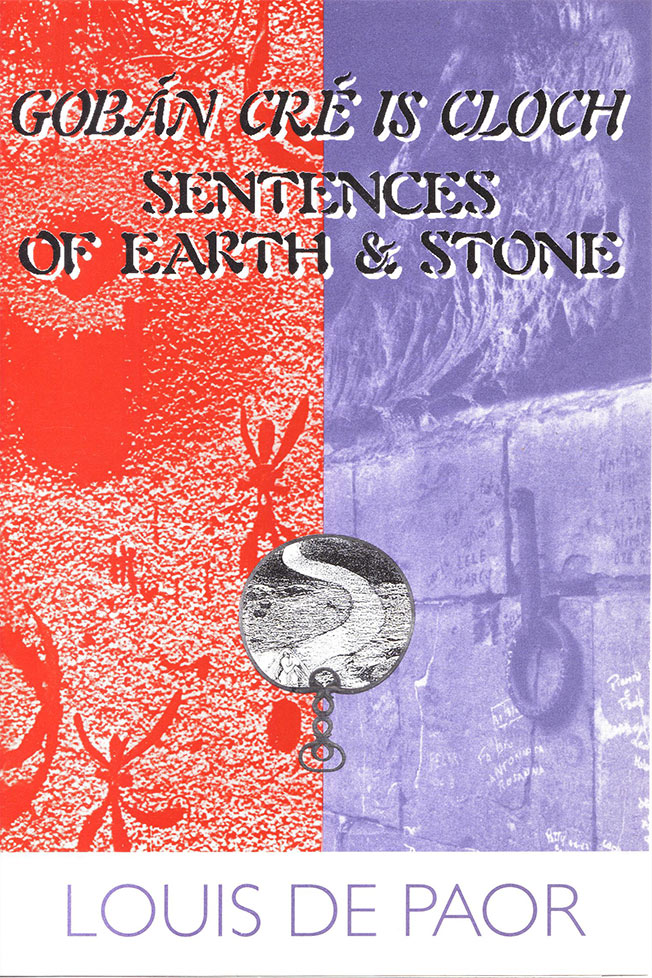

Earth & StoneGobán Cré is Cloth Louise de Paor This is exquisite poetry Robert Verdon, Muse the music of de Paor’s ‘everyday wordbrawl’ continues to exhilarate Lyn McCredden, Arena |

Book Description

Gobán

Cré is Cloth/Sentences of Earth

& Stone is Louis de Paor’s second

collection of

his Irish poetry accompanied by his English translations. These poems

of love, history and memory have been critically acclaimed and are now

reprinted for the first time. This collection was nominated for The Irish Times

Literary Award in

1997.

The terror of distance from family or language invades the everyday. Individual moments are suddenly alert with protest, loss or larger possibility. In our times of the fashionably cool, he writes poems of cruelly informed warmth.

The terror of distance from family or language invades the everyday. Individual moments are suddenly alert with protest, loss or larger possibility. In our times of the fashionably cool, he writes poems of cruelly informed warmth.

Love

poems of such a passionate

tenderness as to take one's breath away.

Tim Thorne

His

sense of the special in the

ordinary... his capacity to tap beneath consciousness, allows an

energetic compassion that strikes deeper than sympathy.

Lynette Kirby

Louis

de Paor can make a genuine

claim on greatness.

Pete Hay

ISBN 1876044063

First published 1996, reprinted 1997

91 pgs

Sentences of Earth & Stone book sample

Back to top

FABLE

THE ISLE OF THE DEAD

DIDJERIDU

ASSIMILATION

MANNERS

GOODNIGHT

AN CAISIDEACH BÁN

THE NOVICE IN THE TAVERN

PISEOGA

SPECTACLES

BELIEVING

SLIABH LUACHRA

VISITORS

THE CREATOR

THE BED ROOM

DAUGHTER

TREASURE

CHANGELING

FROSTBITE

TELLING TALES

THE CORN FIELD

THE GENEALOGY OF EYES

HOMEWORK

APPLES AND PEARS

HEART BEAT

THE LUCKY CAUL

REGROWTH

SCRIBBLING

FABHALSCÉAL

OILEÁN NA MARBH

DIDJERIDU

AN DUBH INA GHEAL

BÉASA

OÍCHE MHAITH

AN CAISIDEACH BÁN

AN NÓIBHÍSEACH SA TIGH TÁBHAIRNE

PISEOGA

GLOINÍ

CREIDEAMH

SLIABH LUACHRA

CUARTEOIRÍ

AN CRUTHAITHEOIR

AN SEOMRA CODLATA

INCHEAN

CNUAS

IARLAIS

AN GOMH DEARG

FINSCÉALTA

AN GORT ARBHAIR

GINEALACH NA SÚL

FOGHLAIMEOIRÍ

AONACH NA dTORTHAÍ

CROÍBHUALADH

CAIPÍN AN tSONAIS

ÉIRIC

SEOLADH

Back to top

At the Margins’ Margins

Gobán Cré Is Cloch/Sentences of Earth & Stone

Simon Caterson

Metre (Ireland) 2001

The Necessity of True Speaking

Alison Croggon

Quadrant November 1997

Gaelic Breath

Lyn McCredden (academic and essayist)

Arena, April-May 1997

‘The Cornfield, Part 4’

Back to top

Books

Robert Verdon (author of The Well-Scrubbed Desert)

Muse, February 1997

Naughty boys, all of them Irish: ‘pointless to pray / for the souls of animals.’

‘The Corn Field’ had me almost in tears; it looks back at a childhood trauma through a prism sharper than mere nostalgia. With his talent for understatement, de Paor is a master of the elegy, the cold-eyed, warm-hearted poem that catches you up when you least expect it.

All these poems arc alive with joy or heartache; the emotions they engender can be scarifying, but all are liberating (and in two languages at that). For once I can truly agree with the blurb on the back: de Paor, as Philip Cleary states, is a ‘rare and radical talent’.

Back to top

First published 1996, reprinted 1997

91 pgs

Sentences of Earth & Stone book sample

Back to top

FABLE

THE ISLE OF THE DEAD

DIDJERIDU

ASSIMILATION

MANNERS

GOODNIGHT

AN CAISIDEACH BÁN

THE NOVICE IN THE TAVERN

PISEOGA

SPECTACLES

BELIEVING

SLIABH LUACHRA

VISITORS

THE CREATOR

THE BED ROOM

DAUGHTER

TREASURE

CHANGELING

FROSTBITE

TELLING TALES

THE CORN FIELD

THE GENEALOGY OF EYES

HOMEWORK

APPLES AND PEARS

HEART BEAT

THE LUCKY CAUL

REGROWTH

SCRIBBLING

Clár

FABHALSCÉAL

OILEÁN NA MARBH

DIDJERIDU

AN DUBH INA GHEAL

BÉASA

OÍCHE MHAITH

AN CAISIDEACH BÁN

AN NÓIBHÍSEACH SA TIGH TÁBHAIRNE

PISEOGA

GLOINÍ

CREIDEAMH

SLIABH LUACHRA

CUARTEOIRÍ

AN CRUTHAITHEOIR

AN SEOMRA CODLATA

INCHEAN

CNUAS

IARLAIS

AN GOMH DEARG

FINSCÉALTA

AN GORT ARBHAIR

GINEALACH NA SÚL

FOGHLAIMEOIRÍ

AONACH NA dTORTHAÍ

CROÍBHUALADH

CAIPÍN AN tSONAIS

ÉIRIC

SEOLADH

Back to top

Reviews

At the Margins’ Margins

Gobán Cré Is Cloch/Sentences of Earth & Stone

Simon Caterson

Metre (Ireland) 2001

The reason why people

abroad tend to

think there are more Australians

than there are is because so many of them are at any given time out of

the country. It is therefore refreshing to find a poet of Louis de

Paor’s calibre travelling in the opposite direction. If not

geographically then linguistically Louis de Paor is as isolated an

exile as perhaps a poet can be nowadays. de Paor refuses to allow the

English translations of his work, or ‘forgeries’ as

he prefers to call

them, anywhere near Ireland. Like his previous bilingual collection,

the new poems, at least in the English, celebrate the newfound

landscape and in particular its big weather, but de Paor also begins to

explore an Irish childhood. His thoughts, it seems, heliotrope towards

home, though he also has some powerful things to say about indigenous

Australians, with whom he as an indigenous Irishman feels an affinity.

It is here that a rich seam is waiting to be worked.

Back to top

A Terrible Beauty Is Born

Poetry and Community in the work of W.B. Yeats, Seamus Heaney, Vincent Buckley and others

John McLaren

Tirra Lirra, Vol. 9, No. 4, Winter 1999

Appropriately, an Irish-born and Gaelic-speaking poet, Louis de Paor, has been able to suggest the link between the oppression of the Irish, the convict system in Australia, and the dispossession of the Aborigines. His long poem on Port Arthur, ‘The Isle of the Dead’, describes first the graves of the English, their headstones facing home to England as the tourist guide justifies their deeds with ‘mouldering eyes’. The poet then describes the graves of the Irish where they

The spare lines allow no sentimentality as they move from the physical details of incarceration by way of the explicatory and condemnatory phrase, ‘devout technology’, summing up the twinned aspiration and process of imperialism, to the ironic message. The gaol that holds the image of God also denies it, but by confining the prisoners together creates for them a community that survives in the chronicle of names on headstones with which the poem concludes. Even those whose names are not recorded constitute a ‘rollcall unopened’, to be known only in the future, but with the power in the present to bow the poet’s head and inflexible knee in supplication to the earth.

This rollcall of the unknown refers not only to the convicts, but to all the anonymous labourers whose work has built the settler society. In the following poem, ‘Didjeridu’, the poet turns to the song of the dispossessed, which, rather than setting rebel hearts to dance, calls up the sounds of the land and its creatures, and

For those able to listen ‘for a minute or two/ hundred years’ these songs ‘bleed from punctured lung’, while our gentle ancestors can only ‘beat the skin of the earth’, feeling nothing. In this admission of an inability penetrate to the meaning of the song, while still being prepared to listen to it, and to the voices of the convicts, lies the possibility of community that, by acknowledging responsibility for its past, will learn to be at home with the land. Louis de Paor, speaking as a latecomer this land, as well as a speaker of the language of the oppressed of the old world, is able express a community that will transcend both the suffering and oppression of the past and the divisions they breed even as we try redress them.

Back to top

Back to top

A Terrible Beauty Is Born

Poetry and Community in the work of W.B. Yeats, Seamus Heaney, Vincent Buckley and others

John McLaren

Tirra Lirra, Vol. 9, No. 4, Winter 1999

Appropriately, an Irish-born and Gaelic-speaking poet, Louis de Paor, has been able to suggest the link between the oppression of the Irish, the convict system in Australia, and the dispossession of the Aborigines. His long poem on Port Arthur, ‘The Isle of the Dead’, describes first the graves of the English, their headstones facing home to England as the tourist guide justifies their deeds with ‘mouldering eyes’. The poet then describes the graves of the Irish where they

Lie as

they did in life on edge

in cramped beds that hurled

them against walls or knocked

them to the floor if they

moved in their sleep,

a devout technology

to teach the thing the body is a jail

to be rent asunder

releasing God’s image

imprisoned within,

they did in life on edge

in cramped beds that hurled

them against walls or knocked

them to the floor if they

moved in their sleep,

a devout technology

to teach the thing the body is a jail

to be rent asunder

releasing God’s image

imprisoned within,

The spare lines allow no sentimentality as they move from the physical details of incarceration by way of the explicatory and condemnatory phrase, ‘devout technology’, summing up the twinned aspiration and process of imperialism, to the ironic message. The gaol that holds the image of God also denies it, but by confining the prisoners together creates for them a community that survives in the chronicle of names on headstones with which the poem concludes. Even those whose names are not recorded constitute a ‘rollcall unopened’, to be known only in the future, but with the power in the present to bow the poet’s head and inflexible knee in supplication to the earth.

This rollcall of the unknown refers not only to the convicts, but to all the anonymous labourers whose work has built the settler society. In the following poem, ‘Didjeridu’, the poet turns to the song of the dispossessed, which, rather than setting rebel hearts to dance, calls up the sounds of the land and its creatures, and

Ancient tribes of the air

Speaking a language vour wild

Colonial heart cannot comprehend.

Speaking a language vour wild

Colonial heart cannot comprehend.

For those able to listen ‘for a minute or two/ hundred years’ these songs ‘bleed from punctured lung’, while our gentle ancestors can only ‘beat the skin of the earth’, feeling nothing. In this admission of an inability penetrate to the meaning of the song, while still being prepared to listen to it, and to the voices of the convicts, lies the possibility of community that, by acknowledging responsibility for its past, will learn to be at home with the land. Louis de Paor, speaking as a latecomer this land, as well as a speaker of the language of the oppressed of the old world, is able express a community that will transcend both the suffering and oppression of the past and the divisions they breed even as we try redress them.

Back to top

The Necessity of True Speaking

Alison Croggon

Quadrant November 1997

Only truthful hands can

write

true poetry, said Paul Celan. Celan, the exiled German Jew who perhaps

more than any other twentieth-century poet attempted to make of the

quicksand of language a place where truth could exist, stands as a

beacon of rigour. His standards are harsh, exacting, extreme. He is a

wound in the side of poetry, an admonition, an exhortation to

attention, a conscience. With Osip Mandelstam, another child of

political and social extremity, he has been called a martyr and a

saint. But it would be more respectful and more accurate to say of them

both, as Rene Char said of Rimbaud, that they were poets, and that is

enough.

Such voices are discomforting. They do not protect themselves, they do not apologise, and despite their disconcerting humility they will not budge from an insistence that the heart must be ‘a place made fast’, that poetry is ‘a unique instance of language’ that matters uniquely. They write from the far reaches of existence, uncertain whether their poems will ever wash up ‘on the shoreline of a heart’. And yet they speak, across the vastness of their silences, in the face of everything that demonstrates such speaking is impossible, that such speaking has no value.

Such voices are discomforting. They do not protect themselves, they do not apologise, and despite their disconcerting humility they will not budge from an insistence that the heart must be ‘a place made fast’, that poetry is ‘a unique instance of language’ that matters uniquely. They write from the far reaches of existence, uncertain whether their poems will ever wash up ‘on the shoreline of a heart’. And yet they speak, across the vastness of their silences, in the face of everything that demonstrates such speaking is impossible, that such speaking has no value.

That’s the

high standard.

No historical age has been hospitable to poets. Poetry is always, as Celan and Mandelstam both said, ‘against the grain’ of an epoch. It often appears that, given this general caveat, we have entered a time when poetry is less possible. The Italian Nobel laureate Eugenio Montale claimed that we were entering a new ‘dark age’ driven by the materialist ideologies of technology, in which the processes of the spiritual organism that are tracked in the poet will increasingly retreat from the Zeitgeist of the age. Poetry, that mode of speech which penetrates the legislative armour of language to remind us of a possible wholeness of being, a possible freedom, a possible truth, is now almost wholly ‘against the grain’. But the urge towards the poetic is a primitive and stubborn expression of humanity that will never vanish entirely.

Poetry is not, and never has been, merely a business of words. Craft, as Celan said, is of minimal interest: one expects craft as one expects hygiene. Living speech escapes classifications, proceeding by a process of constant improvisation, and literature, its cousin, is without exception connected to the act of human breathing, the rhythm of a body, and consequently will always present the disruptions of complexity. The true life of poems.does not exist in their craft, however formally attentive the language, but in another activity the craft makes possible: what one might call the living organism of the poem, a kind of magnetic field around the words that is at once immediately perceptible and impossible to describe.

No historical age has been hospitable to poets. Poetry is always, as Celan and Mandelstam both said, ‘against the grain’ of an epoch. It often appears that, given this general caveat, we have entered a time when poetry is less possible. The Italian Nobel laureate Eugenio Montale claimed that we were entering a new ‘dark age’ driven by the materialist ideologies of technology, in which the processes of the spiritual organism that are tracked in the poet will increasingly retreat from the Zeitgeist of the age. Poetry, that mode of speech which penetrates the legislative armour of language to remind us of a possible wholeness of being, a possible freedom, a possible truth, is now almost wholly ‘against the grain’. But the urge towards the poetic is a primitive and stubborn expression of humanity that will never vanish entirely.

Poetry is not, and never has been, merely a business of words. Craft, as Celan said, is of minimal interest: one expects craft as one expects hygiene. Living speech escapes classifications, proceeding by a process of constant improvisation, and literature, its cousin, is without exception connected to the act of human breathing, the rhythm of a body, and consequently will always present the disruptions of complexity. The true life of poems.does not exist in their craft, however formally attentive the language, but in another activity the craft makes possible: what one might call the living organism of the poem, a kind of magnetic field around the words that is at once immediately perceptible and impossible to describe.

The six books under

review

started me thinking again of the question of the poetic… Of

all these

writers, de Paor is the closest to an intuition of human truth, the

least afraid of the deep vein of poetic resistance. Sentences of Earth

and Stone is an extremely readable book, a virtue of the stubborn

clarity of de Paor’s language. The poems are given en face in

English

and the original Gaelic. I can’t really speak about the

Gaelic, but the

English poems are compromised by a refusal of craft that may be, in

part, a political refusal of the heritage of English poetry. de

Paor’s

aim is to give speech to the unvoiced, the dead and the anonymous

living, and he gives weight in the world of his poems to a tangible

domestic world and the clear but incomplete perceptions of childhood,

written with a simplicity that at its best recalls the unadorned voice

of Patrick Kavanagh. ‘Scribbling’, the last poem in

the book, finishes:

I

can just make out,

A trick of the light

Maybe, a smeared claw

Tagged with the ring of words,

A prop against the

Jamb of nothing,

A breath of air on

The hinge of everything.

A trick of the light

Maybe, a smeared claw

Tagged with the ring of words,

A prop against the

Jamb of nothing,

A breath of air on

The hinge of everything.

This sense of the

contingency of

language runs through the book, an intuition of immanence within the

everyday that notes ‘this never / ending moment already gone

/ in the

whoosh of an angel’s wing’. But de Paor eschews a

tight lyric control

that might push his metaphors further than one step into meaning. I

can’t help thinking of the grace and intensity that inhabit

the poetry

of the Estonian poet Jaan Kaplinksi, whose stringent and pained

insistence on the present, human moment opens into a Buddhist

contemplation of the eternal: de Paor’s poetic impulse is in

similar

territory, but his lack of discipline often slackens the line and

leaves the impulse floundering. His simple language can drop to the

simply prosaic, relying for its emotive weight on unquestioning

political or emotional sympathy. This is clear, for instance, in the

sequence on Port Arthur, ‘The Isle of the Dead’,

which assumes a status

of wronged victimhood for the convicts and generates its energy not

from its language but from its charged subject matter. The truth of the

Port Arthur penal colony is more complex and brutal than de

Paor’s

lament for murdered innocence suggests, and apotheosis for its uneasy

shades calls for a harsher resolution of paradox than de Paor offers in

his rollcall of Irish names, ‘a shower of rain / without

stain that

bows / my head.’

Back to top

Back to top

Gaelic Breath

Lyn McCredden (academic and essayist)

Arena, April-May 1997

I don’t read

Gaelic, though I

wish I did, and so am not eminently suitable to review this book.

However, reading Louis de Paor’s Sentences

of Earth & Stone, his

second bilingual English/Irish book of poetry, I am given some chance

to enter into the words and scenes and character of another culture, by

chance the culture of my ancestors. de Paor is an Irishman from Cork

who has lived and written in Australia for the last nine years. He is

currently back in Ireland for a year, the recipient of the

Seán Ó

Ríordáin Prize.

In performance, Louis reads his poetry in both English and Irish. For the audience, it is a thrilling and a humbling experience. You are invited to listen to poetry as it makes sense and music in two languages so very different in sound and history. It’s not merely the rich, earthy narratives of these poems, but the musical repertoires of the two languages which give such pleasure. The mono-lingual reader like myself must sit humbly with the presence of poems on facing pages in a language and from a culture so different to the English.

The title’s ‘sentences of earth and stone’ suggests contact with a simple, everyday and peasant-based world - ‘the argot of old men / on stone benches ... their gapped mouths / and the sun’ - where ordinary objects and time schemes are invoked. However, the first poem, ‘Fable’/ ‘Fabhalscéal’, elaborates on these old men and their argot: ‘When silence fills their mouths’ with ‘the wooden language of the dead’. It is a metaphysical elaboration in the most palpable of language. The second poem, ‘Isle of the Dead’, is also concerned with death through the things of death: headstones, graven letters, worms and cages of bone. But as in ‘Fable’, it is death as metaphor for living which is a central concern. Death is registered in all its forms: in the land and the weather - ‘the weight of a sky / that drove their easygoing bodies / beyond the unhurried stroke / of their gentle hearts;’ and includes the living bodies which know their destinies: ‘a surplice-white light pouring / from the well of their gapped mouths.’ In ‘Isle of the Dead’ ‘the convicts lie as / they did in life on edge / in cramped beds ... to teach the thing / the body is a jail’.

This latter lesson is not de Paor’s directly, but it is one the poet sees inscribed everywhere in human beings’ treatment of each other. Much of the poetic and political energy is found in de Paor’s searching out the possible reasons for such barbarity. In rough, blunt, short lines the poetry spits out its accusations against those who continue to perpetuate the lies of colonisation and human cruelty:

In performance, Louis reads his poetry in both English and Irish. For the audience, it is a thrilling and a humbling experience. You are invited to listen to poetry as it makes sense and music in two languages so very different in sound and history. It’s not merely the rich, earthy narratives of these poems, but the musical repertoires of the two languages which give such pleasure. The mono-lingual reader like myself must sit humbly with the presence of poems on facing pages in a language and from a culture so different to the English.

The title’s ‘sentences of earth and stone’ suggests contact with a simple, everyday and peasant-based world - ‘the argot of old men / on stone benches ... their gapped mouths / and the sun’ - where ordinary objects and time schemes are invoked. However, the first poem, ‘Fable’/ ‘Fabhalscéal’, elaborates on these old men and their argot: ‘When silence fills their mouths’ with ‘the wooden language of the dead’. It is a metaphysical elaboration in the most palpable of language. The second poem, ‘Isle of the Dead’, is also concerned with death through the things of death: headstones, graven letters, worms and cages of bone. But as in ‘Fable’, it is death as metaphor for living which is a central concern. Death is registered in all its forms: in the land and the weather - ‘the weight of a sky / that drove their easygoing bodies / beyond the unhurried stroke / of their gentle hearts;’ and includes the living bodies which know their destinies: ‘a surplice-white light pouring / from the well of their gapped mouths.’ In ‘Isle of the Dead’ ‘the convicts lie as / they did in life on edge / in cramped beds ... to teach the thing / the body is a jail’.

This latter lesson is not de Paor’s directly, but it is one the poet sees inscribed everywhere in human beings’ treatment of each other. Much of the poetic and political energy is found in de Paor’s searching out the possible reasons for such barbarity. In rough, blunt, short lines the poetry spits out its accusations against those who continue to perpetuate the lies of colonisation and human cruelty:

You must remember

these

were naughty boys who had

to be shown the error

of their wicked ways,’

explained the guide,

ex-army in polished shoes

and priest-clean nails, his

sweet talk fouling the air

with mouldering lies.

were naughty boys who had

to be shown the error

of their wicked ways,’

explained the guide,

ex-army in polished shoes

and priest-clean nails, his

sweet talk fouling the air

with mouldering lies.

‘The

Isle of the Dead’

It won’t be

the words and

actions of the army or the religious who can honour such dead, but the

poet’s, as his poetry momentarily resurrects the forgotten,

in a

rollcall of the long dead: ‘Thomas Kelly, / carpenter, Edwin

Pinder, /

miner, John Bowden, barber... a rollcall unopened... without stain

that bows / my head and inflexible / knee in supplication / to the

earth’. The rough dignity given to such victims of a past

regime finds

its power from the poet’s words, and their anger at the

brutality which

was their lives and deaths. The religious and political forces which

would leave such a rollcall ‘unopened’ are

repudiated, as the poet

forges an angry ‘supplication’ in his art.

But there’s also lightness of touch, and humour, in de Paor’s poetry. Shoes and objects of the household are given life as they sense the onset of summer, that ‘hooligan / hooning around corners / joyriding with the sun’:

But there’s also lightness of touch, and humour, in de Paor’s poetry. Shoes and objects of the household are given life as they sense the onset of summer, that ‘hooligan / hooning around corners / joyriding with the sun’:

At the back of the

wardrobe

behind the broken clock

my grandmother’s shoes can feel

forbidden music touch her dead feet,

click of fingers

clack of heels

smack of lips

on powered cheeks

behind the broken clock

my grandmother’s shoes can feel

forbidden music touch her dead feet,

click of fingers

clack of heels

smack of lips

on powered cheeks

‘Visitors’

Here the dance between

death and

life takes a joyous turn, and the structure of the lines expresses the

verve, part nostalgia, part humour. Generalisations such as

‘the Irish

are musical and nostalgic’ are pretty vapid, so

I’ll just say that

here’s an Irish poet who creates through both registers, but

who also

has a keen sense of the present. The everyday - of children and

parents, of sexual bodies, of things - is created through music and a

contemporary sense of living, upon which the past impinges endlessly.

de Paor likes to tell stories, and many of his longer poems are historically placed narratives of childhood, of loss, of longing. What is most interesting for me is the plangent sense of struggle in many of the poems between life and death, the past and the present, the traditional and the individual. The acknowledgements thank, amongst others, those close to the poet who ‘set me back on course whenever I strayed onto the straight and narrow’. The nice irony of this phrase is augmented by the tensions, inscribed in many poems, between old religious beliefs and practices and more earthy, earthly realities. For instance, in the long narrative poem in five parts. ‘The Cornfield,’ the brutal death of a small child - ‘...her huddled body / small as a wren nesting in a bed’ - is remembered:

de Paor likes to tell stories, and many of his longer poems are historically placed narratives of childhood, of loss, of longing. What is most interesting for me is the plangent sense of struggle in many of the poems between life and death, the past and the present, the traditional and the individual. The acknowledgements thank, amongst others, those close to the poet who ‘set me back on course whenever I strayed onto the straight and narrow’. The nice irony of this phrase is augmented by the tensions, inscribed in many poems, between old religious beliefs and practices and more earthy, earthly realities. For instance, in the long narrative poem in five parts. ‘The Cornfield,’ the brutal death of a small child - ‘...her huddled body / small as a wren nesting in a bed’ - is remembered:

As we

said the

rosary that night

the cold floor hurt our knees,

we made a quilt from patches

of old prayers to cover her

perished soul and lit a candle

at the Virgin’s feet to

keep out the night for a while,

we drugged the bulk of heavy blankets

on stone cold bones

that would never again be warm.

the cold floor hurt our knees,

we made a quilt from patches

of old prayers to cover her

perished soul and lit a candle

at the Virgin’s feet to

keep out the night for a while,

we drugged the bulk of heavy blankets

on stone cold bones

that would never again be warm.

‘The Cornfield, Part 4’

de

Paor often writes like

this, abutting religious and bodily needs

agains each other, in a climate (Irish? Melburnian?) which doubts the

efficacy of prayer, but grimly confirms the need of it also. Sentences

of earth and stone are mortal ones in this volume, but the music of de

Paor’s ‘everyday wordbrawl’ continues to

exhilarate.

Back to top

Books

Robert Verdon (author of The Well-Scrubbed Desert)

Muse, February 1997

This is exquisite

poetry. When I

opened it I was ‘worded out’ from too much

reviewing, but (perhaps due

to my Celtic soul) it revived me in a flash.

Louis de Paor (pronounced more or less ‘de pware’) has a particular talent for striking imagery - ‘a surplice-white light’; ‘useless as a rope on sand / when curiosity slipped its lead’; ‘scoops of wind off the mountain’.

His book is bilingual but sadly I’m not, so I’ll stick to the Saxon translations.

‘The Isle of the Dead’, which may refer to Australia, is a strongly anti-imperialist work, yet lacks the awkward self-consciousness or arch didacticism found in the political works of less accomplished poets. The corner of this foreign field is forever England, perhaps, but it is an England of convicts and their military oppressors, an England of master and slave. And though they are dead, this England, a system of dehumanising brutality driven by greed and hypocritical Christianity, lives on:

Louis de Paor (pronounced more or less ‘de pware’) has a particular talent for striking imagery - ‘a surplice-white light’; ‘useless as a rope on sand / when curiosity slipped its lead’; ‘scoops of wind off the mountain’.

His book is bilingual but sadly I’m not, so I’ll stick to the Saxon translations.

‘The Isle of the Dead’, which may refer to Australia, is a strongly anti-imperialist work, yet lacks the awkward self-consciousness or arch didacticism found in the political works of less accomplished poets. The corner of this foreign field is forever England, perhaps, but it is an England of convicts and their military oppressors, an England of master and slave. And though they are dead, this England, a system of dehumanising brutality driven by greed and hypocritical Christianity, lives on:

‘You must remember

these

were naughty boys who had

to be shown the error

of their wicked ways’,

explained the guide

ex-army in polished shoes

and priest-clean nails, his

sweet talk fouling the air

with mouldering lies.

were naughty boys who had

to be shown the error

of their wicked ways’,

explained the guide

ex-army in polished shoes

and priest-clean nails, his

sweet talk fouling the air

with mouldering lies.

Naughty boys, all of them Irish: ‘pointless to pray / for the souls of animals.’

‘The Corn Field’ had me almost in tears; it looks back at a childhood trauma through a prism sharper than mere nostalgia. With his talent for understatement, de Paor is a master of the elegy, the cold-eyed, warm-hearted poem that catches you up when you least expect it.

All these poems arc alive with joy or heartache; the emotions they engender can be scarifying, but all are liberating (and in two languages at that). For once I can truly agree with the blurb on the back: de Paor, as Philip Cleary states, is a ‘rare and radical talent’.

Back to top