ISBN

1876044292

Published 1999

94 pgs

Back to top

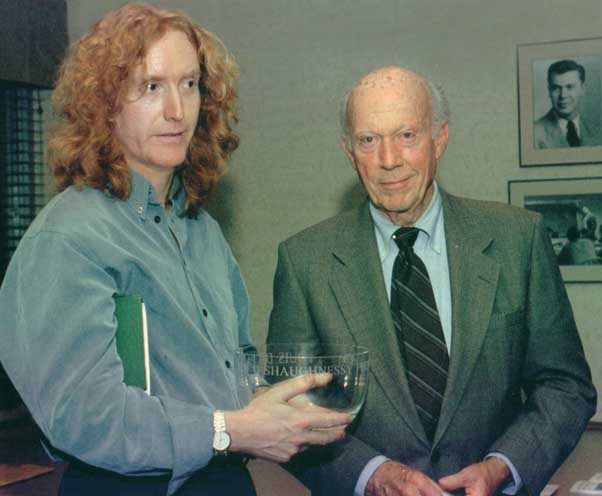

Cork & Other Poems - Winner of Fourth Lawrence M. O’Shaughnessy Prize for PoetryCitation 29 February 2000

Here

on Archbishop John Ireland’s campus halfaway round the globe from

County Galway, we gather not for the customary March observances of

things Irish--no parading or pub-crawling tonight—but for a feast—a

feast both literal and literary. We gather in honour of the Irish poet

Louis de Paor, the language of his originality, and particularly his

seventh collection of poems

Cork & Other Poems.

Published just last year,

Cork & Other Poems is the third of de Paor’s bilingual books after

Sentences in Earth and Stone of 1996 and

Speckled Weather

of 1993. Each of those collections offers de Paor’s own English--what

he terms his “forgery”—of the original Gaelic poem. Each collection

gives a welcome to English, and not a farewell to it.

Because

each of his lines pronounces by turns de Paor’s devotion to the

familial, the intimate, and the sum of Irish heritance, each reader

receives what such other poets in Modern Irish as Máire Mhac an tSaoi

or the late Michéal hAirtnéide have so generously passed on to those

willing to listen. de Paor’s poem “Gaeilgeoiri” raised that question

early on:

Cad leis go rabhamar ag súil?

Go mbeadh tincéiri chun lóin

in Áras an Uachtaráin?

Go n-éistfí linn?

***

What did we expect?

That tinkers could drop in

for a spot of lunch

at Aras an Uachtarain?

That people would actually listen to us?

The

answer, this night, is a plain “Yes.” Remarkably, de Paor’s Irish and

his English forgeries have come to us in St Paul and London—or Boston

and even Dublin—all the way from Australia.

Speckled Weather /

Aimsir Bhreicneach came first, marking off from the outside de Paor’s maturity in 1993.

This

is hardly an accident. It comes, of course, from an essential Irish

circumstance—the necessity to emigrate. Goban Cre is Cloch /Sentences

of Earth and Stone voices that diasporic heritage in a long poem titled

“Oileán na Marbh” or “The Island of the Dead.”

Whether in

English or Irish, those lines keep all of de Paor’s later poems mindful

of the penitential durance of emigration, and not solely because

Australia served as a British penal colony for decades. Visiting the

plots of those prisoners, de Paor declares:

Better to wear a

cowl to hide the shame of

man made nothing, to cover

your face...

***

Ba chuíúla dar liom

cochall a chaitheamh

gan uirísleacht an duine...

The hallmark qualities of

Speckled Weather and

Sentences of Earth and Stone underscore the real presence of every line in

Cork & Other Poems.

De

Paor’s title reminds us that he received the Sean O Riordain prize 1988

and then the 1992 Oireachtas. de Paor was bom in Cork and educated

there. His study of the Galway writer Mairtin Ui Cadhain and his

anthology

Leabhar Sheain Ui Thuma

pay tribute to the poet and scholar Séan Ó Tuama. Like the poets Nuala

Ní Dhomhnaill or Thomas McCarthy, de Paor comes of a remarkable

generation tutored by Seán Lucy, John Montague and Ó Tuama himself at

University College, Cork.

In

Cork & Other Poems,

local and national events speak bitterly and passionately. Early and

Bardic lines pose their sweet and sour against our contemporary lives.

Most importantly, though, de Paor keeps to simple freedom with metaphor

that suddenly and rewardingly complicate a living moment. That is why

the father-and-son scene, a family scene, of “Heredity/ Oidhreacht”

surprises us in its closure.

...ta fíacail ar sceabha

i ndrad mo mhic

gleas chomh hard

le niamh an phearla

ar a ghaire neamhfhoirfe

gan teimheal.

***

...there’s a tooth askew

in my son’s mouth,

bright as a a pearl

in his perfectly crooked smile.

One

of the traditional tasks of the poet’s language is to skew our

perceptions and expectations, to make our straight ways of

understanding crooked, to set our ordinary feelings

ar sceabha.

Whether

forgeries in English or playfully forged in Irish, Louis de Paor’s

poems renew the powers of Irish to set askew the presumptions and usual

preferences of English as we find it in Ireland and Britain, in the

Americas, in Australia.

It is in recognition of those powers

that we celebrate the accomplishment of Louis de Paor by awarding him

the fourth Lawrence M. O’Shaughnessy Prize for Poetry.

Back to top

Cork

Gaol Cross

About Time

Silk of the Kine

Oisí

n

Harris Tweed

Under Ground

Winter

Congregation

The Street

The Light

The First Time Ever

Shocked

Bearing

End of the Line

The Drowning Man's Grip

The Pangs of Ulster

Thirst

Omens

Leprechauns

Rory

14 Washington Street

Nanbird

Setanta

Heredity

Sorcha

Notice

Brewing a Storm

Notes

Clár

Corcach

Gaol Cross

That Am

Síoda na mBó

Oisí

n

Harris Tweed

Bóthar an Ghleanna

mí nádúrtha

Tionól

Díoltas

Fuineadh

An Chéad Lá Riamh

Turraing

Uabhar an Iompair

Deireadh Line

Greim an Fhir Bháite

Ceas Naíon

Íota

Tairngreacht

Leipreacháin

Rory

14 Washington Street

Nanbird

Setanta

Oidhreacht

Sorcha

Neamhaire

Báisteach

Nó

taí

Back to top

Reviews

A

Breath of Fresh Air!

Duncan Richardson

Social Alternatives,

Vol. 20

No. 1, January 2001

de Paor is a breath of fresh air in contemporary poetry, to borrow a

tired cliché but his honesty and unpretentiousness demand a

metaphor of

that kind. For lovers of myth and legend too, his poems are exemplars

of how to use such themes without beating readers over the head with

your erudition. There are two pages of notes on Irish myth and legend

at the end of this book, yet this comes as a surprise, so skilfully are

the images and references worked in. de Paor, who draws on experiences

in Ireland and Australia for the poems in this collection, has a poetic

voice that takes a participant-observer stance, not the self-righteous

or heroic tone so common among writers who deal with traumatic subjects.

When he deals with Ireland’s recent history of conflict, his

images

stem from the cycle of generations, migration and the violent scenes so

familiar from TV yet he does not preach or lapse into mawkishness.

Instead, he offers insight into the conflicting desires in the human

heart, virtue versus fear, and the difficulty of living up to ideals

whatever level of action they may be applied to.

Readers of Gaelic will get double value from this book as each poem

appears in the two languages.

The impact of his work depends on the development within the poem, so

short quotes cannot do them justice. The following poem though shows

how de Paor lets the world speak for itself, through deft handling of a

scene.

Heredity: It won’t come out, / the blood that goes through /

me from my

mother’s side / leaving one snarled tooth / in the roof of my

mouth, /

an itching poet in my head / where demented ideas / scratch in

unseasonal heat, / an ogham stone / shouting me down / with its

unintelligible alphabet. // I put my thumb / under the tooth of

knowledge / and the stone speaks its mind / from the underworld of my

thoughts: / - You’re only a blow-in, / like all that belong

to you; /

hard words like grains of sand / in the corner of an eye / shut tight

as an oyster. // When a blade of light / prises it open /

there’s a

tooth askew / in my son’s mouth, / bright as a pearl / in his

perfectly

/ crooked smile.

Back to top

Gaelic

Poetry...

Nicholas Birns

Antipodes (United States),

Vol. 14, No. 2,

December 2000

Louis de Paor’s Cork

& Other Poems (Corcach

agus Dánta

Eile),

published by Black Pepper Press, seems at first but an intriguing

cultural phenomenon. de Paor (born 1961) is an Irish Gaelic poet who

resided for a time in Australia. Here he publishes a bilingual edition

of his poems with an Australian press. But de Paor’s poems

themselves

are startlingly good, confirmably so in English, and coming through

quite well in Gaelic even for the reader who does not know much of it

(though Gaelic, presumably one of the “European

languages” of the

notorious dictation test for prospective migrants, is an easy one to

crib). de Paor’s freshness of diction, even, and especially,

when using

the most transparent language, is stunning. “...and again

today/ the

light is soft as butter/ on bread fresh from the oven,/ you could put

it in your mouth/ and let it melt/ like holy communion/ on your tongue/

or place it in a jar/ in the medicine box/ a sovereign remedy/ for the

heart.” I will give the Gaelic for the last two lines as the

syntax

falls into place if you realize, not a hard task, that chroi = heart.

“iochshláinte/a chneasóidh do

chroi”. This is poetry one can read, and

re-read, as poetry, not as rhetoric or even as

“verse.” The language is

unbelievably simple, yet possesses an equally unbelievable amount of

depth. The poems themselves have little to do with Australia, and de

Paor, it seems, is no longer resident there. But it shows what

Australian literature can be in a global sense. It can also serve as a

clearinghouse for all sorts of possibilities in global literature - as

if Australia can because of its own “distance”

shake us into

confrontation with reawakened language such as that de Paor gives us.

Back to top

De

Poar:

award-winning poems

Chris Watson (past secretary, Cumann Gaeilge na

hAstráile/Irish

Language Association of Australia)

Tá

in, September 2000

Louis de Paor, who was born in Cork, lived at Melbourne’s

Coburg for

about ten years before returning to Ireland in 1996 to live at

Oughterard, County Galway. Chris Watson, past secretary of Cumann

Gaeilge na hAstráile/lrish Language Association of

Australia, reviews

de Paor’s new book, Cork & Other Poems: Corcach agus

Dánta Eile.

Louis de Paor, fluent in both Irish and English, is a self-translator

who freely changes idioms that work well only in one language, so that

both versions of poems in this recent bilingual collection read as

strong poems in their own right. Readers of the edition published in

Ireland are given less assistance: for them, it’s Irish or

nothing.

The poems based on his departure for Australia and return to Ireland

explore memories and come to terms with the relationships of the

family’s past. ‘Gaol Cross’ recalls that

in flying out from Shannon

Airport, he ‘crossed over/ in my father’s

footsteps,’ and he sees his

grandmother, like Mary at the cross, as a symbol of bereaved

motherhood: ‘When I looked back across the water / the last

light was

dying / in my grandmother’s eyes / as she stood like a statue

in the

dark / looking after us from the foot of the Cross.’

‘Silk of the Kine / Sioda na mBó’ takes

its title, as a note reminds

us, from the old song An Droimeann donn Dílis.

‘When flight number EI

32 / turned its dripping snout / for home, slow / as the white-backed

heifer / that took one last look / at those faraway hills...’

Return

from abroad brings mixed feelings.

He remembers his grandfather’s cow whose own last journey

strangely

resembles his own return home: ‘before climbing the ramp / of

the old

brown truck / to the slaughterhouse.’ Even wryer and more

enigmatic is

the Irish version of the ending, alluding to the opening of the old

song: ‘sara gcuach isteach / i dtrucail donn /

dílis an tseamlais (the

faithful brown slaughterhouse truck).’

In the later part of the book, the family perspective shifts, with

emphasis on being a husband, and father to a new generation. Several

poems are about his response to his wife’s pregnancies. I was

particularly struck by those where he speaks as a father of young

children.

In ‘Notice/Neamhaire’, his daughter asks him to

watch her dance on the

kitchen table. ‘“Jesus Christ,” I say,

“Watch yourself,”’ corresponding

to the untranslatable exclamation, “A dhiabail

álainn / ...tabhair

aire” gives the English poem another

‘watch’ usage in a poem with

several references to cutting and watching. At the poem’s

end, ‘She’s

fallen, her face streaming / like blood from a cut’ and calls

on him to

see her in her distress. However, ‘When I take off / the

blindfold /

she cuts me dead.’ The Irish version is starker in its use of

the

watching and cutting imagery: ‘Nuair a bhainim / an

púicín dem amharc /

tá faobhar ar a súil / dom fhéachant

go feirc. (When I take / the

blindfold from my sight /there’s a blade from her eye /

watching me to

the hilt.)’

Other poems recall incidents and characters outside the family, often

with wit, as in the words of the woman who has to leave her dwelling:

‘I wouldn’t give him the itch / for fear

he’d have / pleasure

scratching it.’

In ‘Congregation’, the noise of a group of

disturbed swans suddenly

resembles the more ominous noises of those who expressed

‘righteous

indignation... in the kangaroo court / outside the Cathedral’

over

ecumenical actions by Mary McAleese. Like this one, many poems, even

when not overtly political, are conscious of the important public and

historical issues surrounding the more familial concerns.

The book is attractive. The cover by Gail Hannah, has a beautiful

overhead picture of a curragh on sand.

Sorcha

When she talks to

trees

plums and apples

land in her lap,

fruit of the vine

and half-blind

strawberries give

in

to her giving

hands.

Cats and dogs know

her

for one of their

own,

their coats speak

in velvet tongues

to her attentive

cheeks.

She goes out like

a light

when the dark

comes in

and stays out till

the

sun climbs from

the snare

of her buckled hair

as morning picks

its way

through the locks

on her forehead,

the slip-knots

of her undark name.

Má labhrann

sí le

crann

péacann

úll

nó pluma ina

glaic,

cuardaíonn an

fhineamhain

is an sú

talún

béal a baise

gan

chraos.

Aithníonn

cait is

coileáin

aon dá

gcineál

labhrann a gcotai

fionnaidh

briathra sróil

lena grua

biorchluasach.

Téann

sí as

nuair a ligtear

an doircheacht

isteach

is ní thagann

ar

ais

nó go

scaoiltear

an mhaidin

as gaiste

búclaí a

foilt,

éiríonn

an ghrian

ionam

as dola reatha

a hainm nach

dorcha.

Author’s note: Sorcha is a girl’s name, meaning

brightness, the

opposite of Dorcha, darkness.

Photo: Sorcha de Paor at Korweignguboora, 1996

Back

to top

Raining

on Mythology’s Parade

Cork

& Other

Poems

Peter Skrzynecki

Sidewalk,

No. 6, July 2000

(pgs 46-48)

[Text not yet available]

Back to top

The

Long and the Short of It: 24 Writers

Cork

& Other

Poems

Michael Sharkey

Ulitarra,

No. 17/18, July 2000

(pgs 222-232)

[Text not yet available]

Back to top

Fine

collection of haunting love lyrics

Tim Thorne

The Sunday Tasmanian

26 March

2000

Louis de Paor has produced yet another

excellent collection

of

bilingual poems.

It is gratifying that Black Pepper has enough faith in his appeal to

Australian readers, despite the fact that it is more than three years

since he last lived in this country, to bring this book out.

de Paor’s reputation in Ireland is firm and since his return

there he

has edited an anthology of Irish poetry which includes work in English

and Irish.

He invariably creates his own poetry in Irish, then translates it into

English.

Having the Irish text on pages facing the English is a constant

reminder of this and must make the vast majority of his Australian

readers, who cannot pronounce, let alone understand the language, long

to hear those pages come to life.

Those of us who have been privileged to hear de Paor read are aware of

the magic that his presence and his voice create in either language.

In this collection there are occasional references to Australia but, as

the title implies, most of the pieces are set in his native city of

Cork and in other parts of Ireland.

There is the wonderful and poignant ‘Rory’, about a

musician who now

plays ‘where

Robert Johnson plays broken / riffs on the boards of a

coffin’.

It encapsulates the dilemma of the exile returning from the other side

of the world after a long absence, while at the same time extolling the

glory of music which transcends narrow cultural boundaries as it

transcends nostalgia and even grief.

There is an element of wry wit apparent in this book which was not such

a feature of de Paor’s earlier work. It is evident in lines

like this

from Harris Tweed: 'In the month of July / in Inverary the grouse /

take to the sky on teatowels.'

These lines follow a list of archetypal images of the smells of

traditional Ireland evoked by a tweed jacket bought ‘for

a song / from

the Salvation Army / in Wonthaggi’.

But it is the haunting love lyrics, the celebrations of the natural

world and the meditations on domestic life that form the core of this

fine collection.

Louis de Paor has the gift of writing with crystal clarity while

presenting challenging complexities.

You can delve into deeper and deeper layers of meaning or just enjoy

the brilliant surface of his poems, as the mood takes you.

Either way, this is a most rewarding book.

Back to top

A

Summer Feast

Cork

& Other

Poems

Ian McBryde

Island, No.

80/81,

Spring/Summer 1999 - 2000 (pgs 203-208)

[Text not yet available]

Back to top

‘Blow, wind,

blow...’: new poetry

Cork

& Other

Poems

Kerry Leves

Overland,

No. 157, 1999

The poet’s English translations accompany his Gaelic

originals;

reading aloud is advisable. Each bit of the ordinary - stockings on a

washing line, a pregnant woman’s back and belly, clocks,

cars, a tweed

jacket still redolent of the barn-floor love-making it once eased; an

eviction at once achingly particular and deadpan commonplace, the lot

of any poor person anywhere - is chanted, caressed, growled, rasped

irifo life. A woman is shot mistakenly by a sniper: a child on

the way

home from mass sees it happen, but there’s no easy lament;

instead, the

painstakingly ingenuous narration, with its dogged rhythms, seems to

follow the entry of this experience into the child’s nervous

system.

The intensity may have to do with the poet’s return

to Ireland after

ten years in Australia; de Paor’s word-music mixes rain,

earth, light,

the body’s alertness. His poetry makes physical

inroads, and searches

out generosities on its shifting Catholic-animist ground.

Back to top

Cork

&

Other

Poems

Cork

&

Other

Poems Cork

&

Other

Poems

Cork

&

Other

Poems