ISBN

9781876044602

Published 2009

186 pgs

$25.95

Don’t Ever Let Them

Get You! book sample

Back to top

Variations on a Theme by George

It’s Not My

First Work!

Unlikely Combinations

Surviving

It’s Good To

Have Friends In High Places

Border Crossings or The

Worst News Is...

How Can You Afford To

Miss It!

‘Jenny, Make It Happen’

Jennifer Isaacs

A Resounding Success

Rosemary Richards

Brass Banding Meets George Dreyfus

John Whiteoak

Complete Catalogue of Works

Stage Works

Choral Works

Orchestral Works

Chamber, Vocal and Instrumental Works

Brass Band

Concert Band

Discography

Film and Video

Bibliography

Index

Back to top

Kay Dreyfus, Monash University

At the Chapel Off Chapel performance and book launch, 14 March 2010

Some of you might be wondering why George would have invited his

ex-wife to launch his book. I wondered the same thing myself but when I

asked George about it, he just looked enigmatic and said he had his

reasons, leaving me to work out what they might be. But there are

plenty of hints in this book that George likes unexpected - even

discomforting - juxtapositions. Consider the little essay that starts

on page 54, George’s speech of thanks on receiving the

Bundesverdienstkreuz Erste Klasse

from the German government at a ceremony in Parliament House Melbourne,

in 2002. ‘I was ejected in 1939,’ George reminded the German Consul

General on this occasion, ‘and now I am being honoured with the

Bundesverdienstkreuz Erste Klasse.’

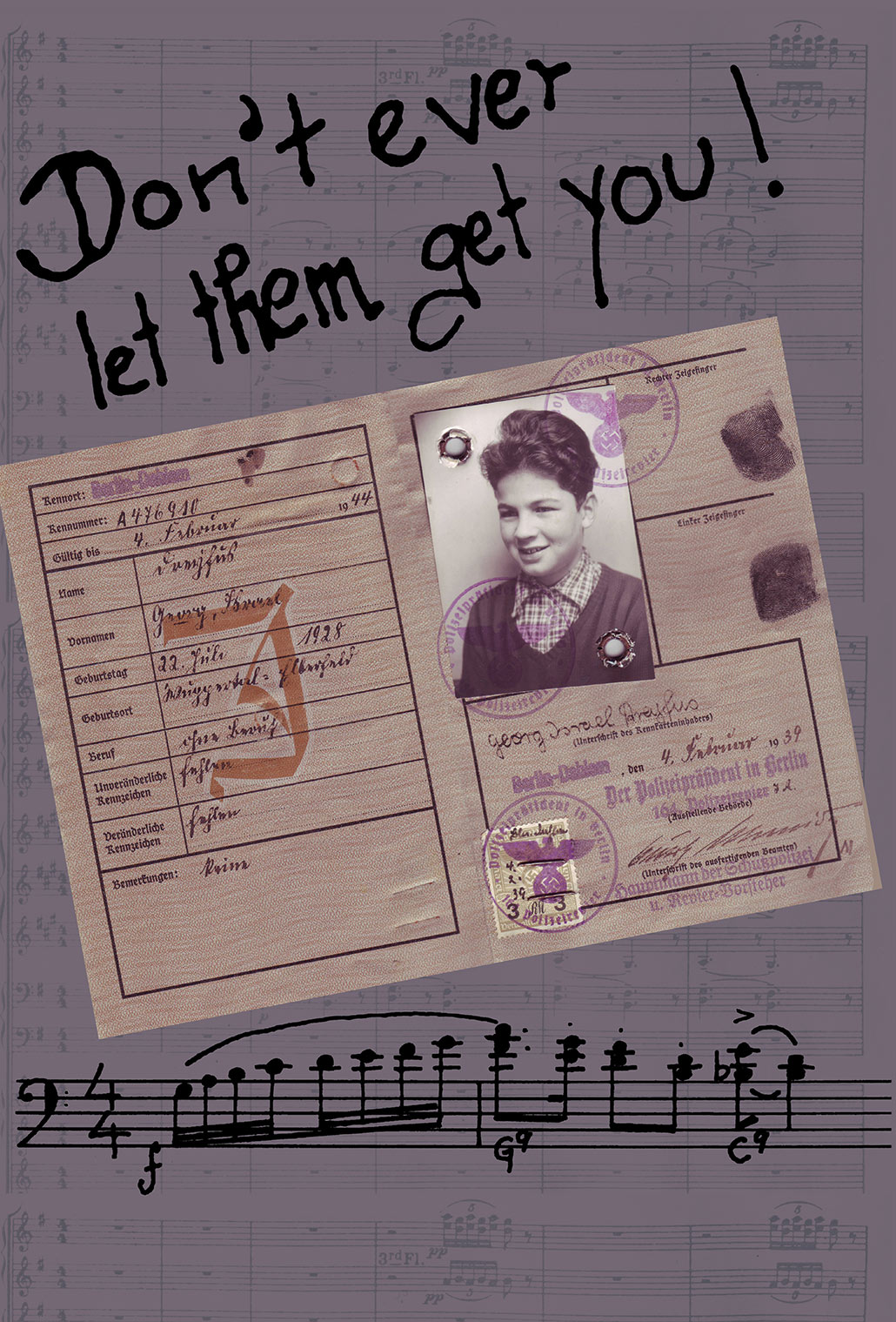

Just to reinforce the point in the book, the essay is illustrated with

the picture of George’s childhood passport that decorates the book’s

very expressive cover, replete with its red ‘J’ for ‘

Jude’,

which was the distinction bestowed on him by the German regime in 1939.

At another point in the book, George writes how he enjoys the

juxtaposition of ancient Biblical prophetic texts with his sometimes

raucous Australian music in his piece

Visions.

Or what about the moment in his setting of the Mass where he misread

the text of the Gloria, and inserted a citation of Australia’s

unofficial national anthem? [Jonathan Dreyfus to play opening phrase of

Theme from Rush.] Is George linking the

Theme from Rush to the Godhead?

For

a musician, George is an inveterate story-teller. Add to that the fact

that he doesn’t like to waste anything he ever thinks of, whether

verbal or musical, and you end up with a trilogy of autobiographical

books of which this present one is the third instalment. The essence of

George’s skill as a composer is his ability to create an inspired,

memorable, classically structured, expertly organised, organically

connected, thematically developed and varied piece of music in three

minutes - I refer of course to his one and only

Theme from Rush [Jonathan Dreyfus to play

Theme from Rush].

The essential quality of his prose, however, is perhaps summed up in

one word, and that word is George’s (see page 46): RANDOM. George’s

prose style is one of free association - one thing leads to another,

this reminds him of that, no one is spared, saints and sinners, friends

and foes. His writing crackles with the energy, vitality and infectious

iconoclasm that have been the hallmark of his style as a musician, a

composer, a performer and an entertainer for these many decades.

Actually,

Arnold Zable should be launching this book, but when I put this idea to

George he said no, Arnold had too much personality! Clearly I was not a

problem in the personality department. I heard Arnold Zable speak at a

conference recently and it seemed to me that he has a wonderful

appreciation of the many reasons why story telling is so important to

us as humans and especially why story-telling is important to people

who have experienced a major trauma in their life. I’d like you to

pretend that Arnold Zable is in fact launching the book, as I am going

to make use of some of his ideas to talk about it.

The cover of

this book bears a most eloquent witness to the defining trauma in

George’s life, At the age of ten he was taken from his family and put

on a boat with his brother and 15 other children and sent away to an

orphanage on the other side of the world where no one spoke his

language. There’s a photo of the children on page 37. George gives us a

glimpse of what it was like for the children (pages 38-39):

It

was a desolate time, Matron gave is as much guidance as she could, but

I was often miserable, I missed my parents and family to such a degree

tjhat there was a hole there that nobody could fill.These

are not George’s words as it happens. But Arnold Zable reminded us that

not all story-telling has to take place in words and the piece of music

we have just heard reflects something of George’s feelings about this

time,

Larino Safe Haven.

George says among other things that this piece is an autobiographical

work, a piece about children without parents, a stolen generation

piece. With its haunting scoring for two oboes and cor anglais, it is a

piece about loss. George was fortunate that his parents turned up a few

months later, and he and his brother Richard were able to leave the

children’s home and tackle the larger task of assimilating into

Australian society. Most of the other children were not so fortunate.

But George had lost a lot. Most grievously, he lost his grandparents,

and late last year Jonathan and I went with George to Wuppertal to see

the memorial stone that had been placed in the pavement outside his

grandmother’s house to commemorate her death. George also lost his

German musical heritage. As John Whiteoak writes in his wonderfully

affectionate chapter on George and the brass band movement, ‘George has

always felt most connected to the only partly recovered European high

art cultural milieu that was taken from him as a child’ (pages 99,

126). George’s stories, like his music, are full of references to his

German musical heritage.

Larino Safe Haven, for instance, is an example of

Durchkomponiertevariationentechnik to be compared to Beethoven’s

Septet op. 16, Brahms’s

Variations on a theme by Joseph Haydn Op. 56a and Max Reger’s

Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Mozart Op. 132. I hope you thought of all that while you listened to it.

Larino Safe Haven

is a piece about surviving. In fact, this whole book is about

surviving, as the title suggests, and not just about children surviving

the antisemitism of the Third Reich, but about George surviving in

Australia, as a musician, a performer, an entrepreneur and a free-lance

composer, something that no one before him had done and few have done

since (Whiteoak page 125 ). More than that, though, it’s about what

George calls ‘survival revenge’. George is not a man to take

disappointments quietly. On the contrary, he turns them into

performance opportunities. George writes his very own revenge arias,

joining a noble operatic tradition that stretches back to

Don Giovanni and beyond. So for example on page 26 we find his catalogue aria of opera stoppers: to a backing of music from his first opera

Garni Sands he sings, in alphabetical order, the names of all those he considers responsible for preventing his opera

The Gilt-Edged Kid

being performed by The Australian Opera. [Jonathan Dreyfus/George to

sing.] ‘Transportation to the cultural Hades for the lot of them’,

trumpets George on page 26, ‘that is, for those who are not already

there’. Another echo of

Don Giovanni!

George likes to note those of his cultural enemies who are dead. On

page 5, we find his musical insult tribute to Clive Douglas, another

dead and a long-forgotten Australian composer who, as a second or

third-rate resident conductor for the ABC, made George’s life a misery

in the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in the 1950s and eventually had him

dismissed. [Jonathan Dreyfus/George to sing.] James Murdoch, author and

commentator, was unwise enough to pen a critical quip about George’s

Symphony No. 1

- it was, so Murdoch said, a ‘decided disappointment’. Undeterred,

George set Murdoch’s entire text to music, made the song the

centrepiece of a one-man show he performed all around Australia and in

Germany. [Jonathan Dreyfus/George to sing

Deep Throat.]

There are fourteen more verses of that one, but I think you get the

picture. George enjoys his musical revenges. And so can you if you buy

a copy of this book!

Arnold Zable distinguished three different

aspects of story-telling. First of all, he says, there is expression:

that is when the story-teller, in this case George, tells the

reader/audience things that he considers to be important about himself.

Secondly, there is impression. That’s when the story-teller tells the

audience things he considers important about other things and people.

This book gives the reader quite a rich counterpoint of impressions: we

get George’s impressions of other people, often vengeful, as we have

seen, though not always. Then we get other people’s impressions of

George, also sometimes vengeful, often bemused, frequently quite

affectionate. We get George’s versions of other peoples’ interactions

with him, and then we get other people’s versions of their interactions

with George. There’s a lot going on.

Although George is at

centre stage for most of the book, his is not the only narrative voice

that is heard. In the second part of the book, three invited authors

explore George’s encounters with three different aspects of the

Australian musical scene. The common theme of this part of the book

could be said to be that of ‘cultures in conflict’. In one corner we

have George, embodying his own unique fusion of German musical

imperialism and what John Whiteoak calls his ‘gumnut Australian

nationalism’. I think George would agree that the

Selections from the Sentimental Bloke

that we are about to hear is a delightful example of this fusion. In

the other corner we have lined up variously, the unsuspecting amateur,

the deeply conservative fifth generation brass band enthusiast and the

dignified but profoundly different traditional indigenous musician.

The unsuspecting amateurRosemary Richards tells the story behind George’s composition

The Box Hill Gloria

- you will hear an extract from this piece later this afternoon. This

is one of George’s special occasion cantatas, written to commemorate a

particular event - in this case, the establishment of a settlement at

Box Hill - and, until today, given only one sonically memorable

performance in 1985 as part of the State’s sesquicentennial

celebrations. On that occasion, more than 200 performers outnumbered

the audience, but the sound was spectacular - ‘sublime’ in the

words of one commentator. According to Rosemary, the event was

memorable in other ways. Her essay documents the impact of the

collision between her self-confessed naïve enthusiasm for the creative

idea and the reality of organising every amateur musician in Box Hill -

nine different amateur choirs and instrumental groups. She offers

tragic testimony to her folly in an image of her car, wrecked in a

moment of stress associated with this event, and then rusting in her

driveway with plum trees growing through its roof. She also describes

the impact of George’s musical expectations on the members of the Box

Hill TAFE student choir, most of whom, after one rehearsal with George,

did not turn up for the performance. Not George’s first choral

disaster. He himself tells the story of another walk-out when he

rehearsed the Melbourne Choral Society in his sacred choral work

Visions. But for the details of that, as George himself would say, you will have to buy the book.

The brass band enthusiastJohn

Whiteoak’s essay deals with George’s encounter with the brass band

movement. This is a very different story. George wrote his first score

for an Australian brass band in 1969, when he composed the music for

the Australian pavilion at Expo Japan, in 1970. In 2003, he

composed his ‘Fanfare for the New Dome’ of the State Library of

Victoria, a splendid multi-directional work that was also played at his

Hawthorn Town Hall concert last year. George was commissioned to write

a special piece for the Australian tour of the Grimethorpe Colliery

Band in 1982. Over three and a half decades, a number of his most

successful film and television themes have been arranged for brass band

by some of the most skilled musicians working in the movement. His

music is published by Wright and Round, England’s leading publisher of

music for brass band and a CD of just about the whole lot, performed by

the Kew Band with George conducting, has been issued by Move Records,

including of course... [Jonathan Dreyfus to play

Theme from Rush]. There is nothing ephemeral about all that.

John

scrutinises every aspect of George’s engagement with the brass band,

noting ‘the awesome intensity of George’s will to survive

professionally’ and asking how comfortably such intensity might sit

with the rather different ethos and agenda of amateur community

music-making. The result is a wonderful overview of the history of

banding in Australia. John also critiques George’s engagement with

Australian folk-music, an essential part of George’s self-definition as

an Australian composer, largely derived from the pages of John

Manifold’s Penguin Australian Song-Book. But as George himself says on

page 47 of this book, ‘ignorance is no handicap’. Critical though it

may sometimes be, John’s essay is full of his regard for George’s

achievement. So much so that John even offers to break a 35-year

embargo and attend the National Brass Band Championships should George

ever be invited to write the test piece. Something to aim for, George.

The indigenous musicianThe

last of these invited essays is, perhaps, my favourite. It tells the

story of the events that led to George being commissioned to write what

some people regard as his most original composition, the

Sextet for Didjeridu and Wind Instruments.

George is not really a central character in this story. Instead we have

Dr Herbert Coombs, Chairman of the Australia Council, Governor of the

Reserve Bank and chief patriarch in charge of Aboriginal affairs in the

early 1970s. The narrator is Jenny Isaacs, Dr Coombs’s personal

assistant at the time, and the person, who ‘made it happen’. when Dr

Coombs decided to stage a creative exchange of music making between the

Adelaide Wind Quintet and a selection of Aboriginal musicians in the

remote Aboriginal settlement at Yirrkala, in the Northern Territory.

What follows goes beyond any ideas you might have of cultures in

collision, but the narrative yields some wonderful images and

descriptions. The Quintet arriving at their motel at Gove - a series of

trucks arranged on their sides around a tree, boiling hot, no air

conditioning, dunny out the back, probably full of flies. Enter the

tour manager, a formidable lady named Miss Regina Ridge, wearing

stockings and gloves. The meeting with the head of the Aboriginal

community - no chairs were provided, everyone sat on the ground under

trees, Miss Ridge still in her stockings and gloves. The concert, with

the Aboriginal MC equipped with stop watch and megaphone stopping each

performance after ten minutes, ready or not. The audience members not

clapping but getting up to dance if they enjoyed an item. And yet, in

spite of all this, marvellous music-making and a real sense of

connection between European and indigenous musicians and a marvellous

creative outcome... [Jonathan Dreyfus to play

Theme from Rush]. No, no, not that marvellous creative outcome, the

Didjeridu Sextet.

At this point I should explain that one of my aims in this speech was the mention the

Theme from Rush

[Jonathan Dreyfus to play] more often than George does in his book. But

to find out who won [on top of Jonathan Dreyfus] you will have to buy

the book. That’s enough Jonathan Dreyfus [send Jonathan Dreyfus off].

The

third aspect of story-telling is what Arnold Zable called mirroring.

But what sort of a mirror does George hold up to his Australia? What

sort of place is it, and how does George fit in? Well, to find the

answers to those questions you will just have to buy the book. But

there are some odd juxtapositions. For example, on page 9 George

describes how as a young man of 21, in 1949, he worked on a setting for

soprano and large orchestra of texts in German extracted from Goethe’s

Wahlverwantschaften.

Goodness! What a project for late 1940s Australia! Then there is

George’s hangup with opera - nothing but trouble there. He keeps on

writing them though the Australia Opera refuses to play them, even if

he has had two premiered in Germany. You can find a list of the reviews

of the German performances on pages 27-30 of this book. I am not sure

if George has set these lists to music, but he certainly read them out

during his one-man show. John Whiteoak says that George himself is a

brass band, particularly when in self-promotional mode: exuberant,

loud, not at all in need of amplification. However, like the brass

band, George can be said to have been and to be a meaningful and

functional presence in Australian musical life. As this book shows, he

possesses in large measure a bundle of qualities that have not only

enabled him to survive in his Australian exile but to thrive and make

his mark against all the odds. George has given Australia its

alternative national anthem. [Jonathan Dreyfus offstage plays

Theme from Rush.]

But what has Australia given George? Most importantly of course a safe

haven, but also a mixed bag of opportunities out of which he has

created the colourful narrative of his life, and an impressive list of

compositions that includes music that has given many people a great

deal of pleasure over a long period of time. It only remains for me to

declare this book launched, to encourage you all to buy a copy - George

would not be happy if I didn’t do that! - and wish George a long life.

Mazeltov!

Back to top

From Suz’s Space Blog:

George

Dreyfus is more of a musician than an author and his book launch

demonstrated that quite dramatically. Proceedings were interspersed

with music. We started off with Dreyfus playing with his son, Jonathan.

They did a nice rendition of the theme from

Rush which

Dreyfus wrote in 1974. This music has become very iconically Australian

which I find rather strange as Dreyfus was born in Germany in 1928 and

only arrived in Australia in 1939. On the other hand, the bulk of the

population in this country is composed of immigrants and yes, I’m

looking at the past 200 years. Before that the inhabitants had been

here for thousands of years so they don’t count as immigrants.

Getting

back to the book launch. Some of the other music we were entertained by

was: the theme of The Adventures of Sebastian the Fox; Larino, Safe

Haven; and The Sentimental Bloke. The music was wonderful and the jokes

were thick and fast in some areas. I don’t know about you, but most of

the people I know do not enjoy good relationships with their

ex-spouses. There is the odd person that manages that and Dreyfus,

being a rather unique person has managed to have a good enough

relationship with his ex-wife Kaye that he asked her to launch her book.

Kaye had much to say about him. This included phrases such as:

# ignorance is no handicap

# unexpected, even uncomfortable juxtapositions. (I think she meant his music.)

# Random – free association

# George is unique

# Turns disappointments into musical opportunities

# He is a meaningful and functional musical presence in Australia

Back to top

Don’t

Ever Let Them Get You!

Don’t

Ever Let Them Get You!