|

Book

Sample

Salt and Pepper Sonnets

Jock

Jock liked to perch on the front veranda’s concrete steps

and scrutinize the clouds (like Roman entrails) the sky.

He always wore a tall-domed black hat, waistcoat, had pets

by his boots: a plump orange cat, a charcoal ochre-eyed

dog, Duke, whom only my grandfather could entirely trust.

Between rich stories, Jock would decipher the tacit heavens

scrupulously: tomorrow sun-licked, the next day tempests.

A miner, erudite amateur geologist, for whom the long caverns

and wriggling reefs beneath Bendigo were quite without mystery.

His oblong Yorkshire yet Irish face, his brown eyes, spelt warmth

when sober. Eva, a Hannan, worked the house, distributed hilarity

while she kept an eye on her husband’s moods from citrus dawn

to black night, and hid the beer inventively before she slept.

When he died she went to the veranda (the pets had fled), wept.

Eva

grandmother

Eva shrivelled, following that somnolent pneumonic death.

Once indefatigably buoyant, an irreducible woman,

as pillowy as the suet dumplings she cooked. He left

her profoundly puzzled, cast adrift in some no-man’s

zone. She padded cautiously around, or sat, a loose sack

on his frayed chair – her repartee and wit, Cork-sharp,

now blank and blunt. Her hair hung like grey flax.

Her loud gregariousness became a cloaked silent harp

at dinners, afternoons of whist, even family affairs.

She toured Australia in a bus of merry widows. A ploy

which worked for a few weeks... then that cavernous stare.

Her widowhood her biological loss had exterminated joy,

and in its place colonic cancer grew: a huge unexplained

tumult. Suet-white, Eva joined her husband in boiling pain.

Birth

The mother screams and screams, blood curdles

as father, husband, stands, petrified, stunned,

unable to comprehend why these colossal hurdles

of pain occur, these detonations in her lungs,

pelvis and abdomen, why this doublehandedness:

gift-bearing with one, gouging out with the other?

So, right at the very start we have ambivalence,

as if young life must present old death to lovers.

The nuns and priests talk, still, of original sin.

Old wives tell tales of rapidly unremembered pain.

Biologists claim that maternal bonds would wear thin

without these rites of passage: Medea again and again.

At agony’s climax she ejaculates: Jesus Christ.

There are moans and moos of joy. The baby shrieks.

Breasts

I must confess, without patronage, I enjoy them all,

especially those whose areolae jut: the shape of pears.

I crave the mountainous ones, the feral, the small,

those that loll down to the waist, the upwardly austere

with the cream flesh and baroque architecture of bananas,

and surmounted, when aroused, by sarcastic black nipples.

I am prone to draw them out from their apricot pyjamas

at parties, between lips and teeth, relish the ripples

as they bounce and balloon and blush beetroot at climax.

Sometimes I merely wish my wriggling face be smothered,

to insert my mouth, potato snout, between a cleavage’s crack,

to feel, underneath, that once again I am being mothered,

that behind each breast’s ancient yet diaphanous silk

lie serene reservoirs of panacean and balsamic milk.

Divorce

It can be here that honour is most put to the test,

except when separation has been judicious, mutual...

each has fallen out of love, or into enmity. The rest,

at worst, can emulate the hounding of a criminal,

or range between custodial revenge and avarice.

For those still besotted there must be ritualistic

retribution – less Medea-like, but a saving of face,

a polishing up of public pride, so shit does not stick.

The insult of such a loss can twist passion into hate,

so with the flair of a Bernhardt or Olivier, a role

can utterly mask the utter love beneath. She waits,

he waits, in an empty, stale, sheetless half-cold

bed, listening for the sound of footsteps, bare

preferably, of a loved one, or children, on a stair.

McDonalds

McDonalds and its swift nutritious food have been much maligned

by those envious of such success, or foes of America’s

soi-disant evil.

Da Vinci, Michelangelo, had they been chefs today, would’ve

designed

the same product, and never thought of addressing a wall or easel.

Then there are those acrimonious analysts and bigots who accuse

McDonalds of indulging in, propagating, the latest manifestation of

America’s obsession with (and concomitant exploitation, abuse,

mincing employees) slavery. In truth, their young workers love

the long hours, the unremitting education, the cherished chance

to secure an unbudgeable position on the lowest but broad rung

of a great ladder. Besides, McDonalds is philanthropic, gallant,

supporting children’s hospitals, adolescents,

society’s unsung.

So, folks, fang into French fries, mayo, the thrift of a SuperMac:

the world has yet to unearth a grander antidote to heart attacks.

Sunsets

I most enjoy those that are brazen and orange

when the sun resembles a buttock of succulent fruit

and declares that the day has been one long triumph,

and that we must tap-dance to dusk in our very best suit.

I least enjoy those that are thin, concentrated red

extruding (between lengths of grey metallic cloud)

lances and lasers which drill me with loss and dread,

and twist evening into, not a lemon tent, but a shroud.

The sun then is bipolar, extreme; even in repose

he exhibits moods of murder or of jubilant magic.

For, unlike the suave moon, the sun’s a primitive force,

and we are its subjects: now guffawing, now tragic.

Sometimes, we bounce like baboons on his back,

at other times we are irradiated, parchment flat.

The

Wind of Madness

‘I have felt the wind of the wing of madness,’ wrote

Charles Baudelaire in his book My Heart Laid Bare.

Insanity is a swirl: the brain twists as if on a rope:

a tumbleweed, small round tree, whipped by violent air.

Once lunatics were frog-marched, banished, to the sea,

where another brand of wind propelled their ships of fools.

Next they were confined, like masochists in monasteries,

or half-eaten lepers, in dungeons too maggoty for ghouls.

The Age of Enlightenment saw them released on sprees

of anarchy, orgies, noonday masses, lampooning officialdom.

So, once again these putative fruitcakes were seized,

certified, manacled, and caged in humourless asylums.

More recently we have inserted needles, alcohol, and slit

lobes, tried coma, electric shock, drugs: for brains on stilts.

Joy

Rarely unalloyed, she comes attired in tinsel

and froth, and scoops you up in fragrant arms,

offers keen breasts, humours, juice: ecstasy rinses

glands, soul, and brain; then you collapse, disarmed.

Next he might arrive in motley, a great buffoon,

or as an oracular judge, a Moses, a sage curmudgeon,

to save the lost day and exorcize spinal gloom.

Melancholy plods lumpily along; joy streaks: urgent,

a flashing vision, intellectual sensual force,

different to happiness, contentment, which are earned;

like luck, unexpected, a dream in which a purple horse

appears conducting a black female President to the green

lawns of the White House. We wake up, incredulous, drained,

but enhanced: this could not possibly occur again.

Friendship

Much prized by Aristotle and his peripatetic school,

yet underestimated, in particular if compared to love.

Even so, friendships arrive and vanish as a rule.

Sweet antic children are the most treacherous: they club

inseparably, as thick as Jesuits one minute, the next

awarding heaped cold shoulders to a sudden leper.

Those established in hormonal adolescence can be best.

Others, revisited, find old soulmates somewhat wetter.

A congregation of friends can provide sepulchral relief

to the loud congresses and rabid epilepsies of sex.

Such companionship is a form of seasoned empathy,

with coded conversations that dexterously circumflex

the ego. Such care, bizarre en masse around our world,

helps uncoil selfishness, in which you too can be curled.

Bergson

We descend the long and convoluted lanes of memory-land,

incandescent, sharply lit, but walled with blanket fog...

grey, undulant, like the surfaces of a brain, and

at no time diverge, fearing the very worst. So we hog

the path and smile, light bouncing off pink spectacles.

At crossroads (Oedipally marked?) feet instinctively veer

towards the tunes of larks, sopranos, satisfied bulls,

far from the screech of vulture, lunatic, owl, hyena.

All of a sudden, as we troop along, the murk could lift

or dissipate, unveiling that spacious mirage, our ideal:

Wordsworthian emerald hills, apricots the size of fists,

waterfalls, Edenic beauties, fowl and fish in pubic valleys.

We sigh, soak up the wilful innocence and grace, turn around:

the fog has reappeared, hissing like steam from the ground.

Fear,

Time, and Matter

The older we become the more fear creeps up,

seems integral to longevity, not approaching death.

This fear betrays an anguish, a lack of trust

in the stout and fixed existence of things on earth,

their possibly slippery status, real or unreal.

We are anchored to the concrete and palpable,

and find ourselves doubly vigilant: banana peels,

removing dead leaves on a steep roof, branch-fall.

Yet a fractured wrist, hip, skull, seems banal.

Deep down this fear knits with time and its processes.

Our terror makes us obsessively, slavishly, punctual,

afraid, if late, of a grotesque universal emptiness.

We turn and we grasp at clocks as if they were

the last vestige of sharp reality threatening to blur.

Earnestness

for Don Watson

This dull skin-deep distemper now enjoys fierce increase,

despite proliferating Festivals of Comedy, political farce,

and the global canonization of democratic mendacity.

Where are those parliamentary beaux-esprits

who could shaft

the gormless, the super-sincere Pecksniffs and nincompoops?

Where are the slashingly hilarious and pungent columnists

of broadsheet and magazine? Instead we must endure a school

compressed to two dimensions by slabs of facts, statistics,

those mesmerized into platitudinous and cyberspatial stupors

by fifteen-second bites, overnight jargons, istantaneity.

Where the hell are our Aristophanes, Molières, Swifts, or

perhaps even the odd dyspeptic survivor of Cultural Studies?

Can we be devolving so that irony, sarcasm, are on the brink,

and a lobule of our brain, wit’s soul, is poised to shrink?

Autumn

Leaves

Eventually eating, sleep, and day-to-day chores,

seem just as satisfactory, stimulating, as sex.

We amorously polish, buff, the knob of a door,

lovingly drill a hole, and squeeze a Wettex.

Perhaps this points to eye-gleam, lure of the chase,

leg power, becoming less instinctive, commanding.

Perhaps the vista of a new relationship grates,

even those fleetingly adhesive pacts of brief flings.

So, foods can attain a Rabelaisian erotic pleasure:

oysters, spinach, pigs, figs, uncouth cheese, eel.

Sleep becomes a concupiscence beyond temporal measure,

as our unconscious loses all point, function, zeal.

Lovemaking merely beds down among this sensual senescence,

in which every hour enshrines delayed detumescence.

I.M.

Brian Sweeney

Ireland’s legendary Sweeney flew and perched in trees.

Brian flew away from school, perched at racecourses,

eluded truant officers, nuns, lounged at theatre matinees,

chatted up usherettes, trainers, jockeys, even horses.

He enshrined a gold standard of hack Hibernian charm,

and, most importantly, bore no counterpoint of hate,

despite ferocious teeth. A chairman of urbane calm

and etiquette, he tempered me, a hothead and ingrate.

Otherwise irascible, like his spruce soulmate Killen,

this rogue raconteur made routine living into a carnival.

I think of Brian as blending Behan, Albert Finney, Villon,

and my dead father... I became a surrogate son-in-law.

Friend of archbishops, the famous, a near Walter Mitty,

how apt that Brisbane’s last leprechaun died in the Holy City.

I.M.

Yvonne Rotstein (Marini)

Yvonne Yvonne, to kiss today that fine forehead

and to find it so cold, as cold as Mount Olympus

in deep December, betrayed the warmth of our years

together, you an actress, singer, I a dramatist,

such friends, companions, colleagues, despite disputes

and points of order, brawls, ideological and theatrical,

I of the Australian persuasion, you an imp and Greek.

I shall never forget, until my last long December

(nowhere near Olympus), your charm, your energy,

that ease and elasticity on the long hard planks

of the stage, within the Pram Factory’s stageless stadium,

Because at that time, and later, you were quite unsung,

it pleases me now to sing this song: long, long, and long.

I.M.

Dinny O’Hearn

He hid in a haystack to elude the long arm of the Lord.

Dog-collarless, a scavenger, he then holed up in St Kilda,

finding a room in a rooming house run by a buxom bawd,

who taught him everything he ever knew about love: Matilda.

An M.A. in French, marriage, surfing, squash, ensued.

Gregarious, allergic to soap, a paragon of bad taste:

he loved mohair pullovers, Australian fiction, and stews.

Yet just as riveting were his bigotries and pet hates:

spaghetti, lettuce, pinot grigio, the middle classes, liars.

Scrags and fashionplates were drawn to his bull chest, deep voice,

blue dress-dissolving eyes, bog-trotting elan, a dial full of ploys

even when, numb from Jamiesons, he extracted teeth with pliers.

Well, dear friend, love-charged politician and deep diplomat,

your death, from vortex to vacuum, still leaves us flat. |

Eve

She solemnly lifted

her head

for the last time,

peered at a dome of blue

which once for her was heaven.

She closed her eyes, demurely,

for the last time,

felt the white air encase her skin

like swaddling, or bandages.

She released a long slow sigh

for the very last time,

expunged all oxygen,

for her, now, a hypocritical gas.

She listened to her red corpuscles choke,

green free at last at last

from the human rat race,

the anomie and glut

of our brave new globe.

|

Reviews

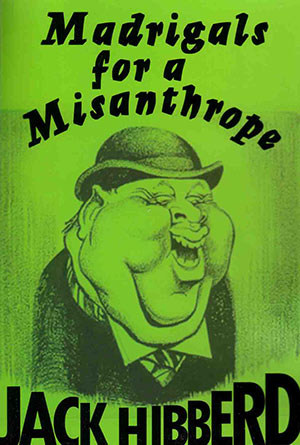

Poetry Survey : Jack Hibberd - Madrigals For A Misanthrope

Oliver Dennis

Island, No.

101, Winter 2005

For someone who has long

held a

reputation as an irreverent dramatist, Jack Hibberd can write

surprisingly formal poetry. A number of these poems are sonnets,

ranging from elegies and ancestral portraits to a set of translations

from Baudelaire. Acerbic and despairing, Hibberd’s work often

responds

to life’s cruelties (as one poem has it: ‘I

comprehend / that life

itself is punishment’); it also expresses disgust at our

endless

capacity for selfishness and violence, and specifically targets famous

Nazi figures: ‘A model for tasteful totalitarians, / beyond

causes,

ideology, race, caste, / the über-Hitler to some historians, /

a

stylist, he made Stalin seem gross, daft’

(‘Reinhard Heydrich’). In

contrast, Hibberd elsewhere writes a good deal about sex and the

consoling influence of love: ‘Often our branches / caress,

rub, touch;

/ not quite as often / they thrash’ (‘Siamese

Love’). Excluding a fine

version of ‘Le Chat’, which speaks magnificently of

Jeanne Duval’s

‘coffee limbs and curls’, his metrical writing

tends to appear somewhat

strained. In fact, one of the most likeable poems in this collection is

pure doggerel. ‘Poem No. 2 for Bill’, about

‘a piebald hound’ that dies

of heat exhaustion, shows him in complete control of his medium,

employing language he is perhaps used to reserving for the stage.

|