|

Album of Domestic Exiles : Andrew Sant |

||||||||

Book Description Sant’s poetry is notable for its quizzical and analytic teasing out of resonances... underlying his close attention to detail is a sophisticated poet's ‘raid on reality’ in order to bring back multiple possibilities and a continuing search for clarification. The Oxford Companion to Twentieth Century Poetry Andrew Sant is a generous poet. His poems are inviting, with an ease of rhythm; carefully crafted, their tone is conversational, even chatty... His observations are sharp and he evokes atmosphere with confidence. Susan

Schwarz,

Australian Book Review

A poet of lively and intelligent curiosity and fine powers of observation. Alan Gould, The Canberra Times ISBN 1876044217 Published 1997 71 pgs $19.95 |

|||||||||

Book Sample

Reviews

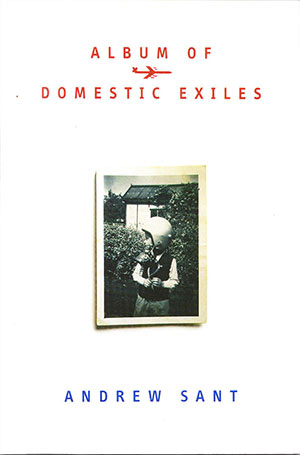

Book Reviews : Album of Domestic Exiles David Yezzi Verse A Londoner by birth, Andrew Sant resides in Tasmania, and it is this continental drift that underlies the poet’s sense, in his fine fifth collection, of exile at home. Mindful of the impermanencies of place, the relocated Sant is everywhere the oddball, neither native nor newcomer. Through their far-flung settings - England, Australia, New York, and Indonesia - his poems convey not so much the comforts of a global village as the dislocation infusing Sant’s world view with a brawling restlessness and hardscrabble redemption. Sant’s title poem, with its sequence of homages to such quaintly antique artifacts as vinyl recordings, candlesticks, and old photographs, recalls the outmoded objects and observances of the postwar generation: Oh children of the

fifties, this exile

within formal borders is but the shadow of the exile into which now you’ve grown... From a nation of holidays, hop-scotch, and knee-length skirts; of hampers and shillings and the last 78s; of Be Seen and Not Heard (the pre-TV screen); parents, Royalty, slap-stick comedies; and black and white snaps within albums few will ache to see unless an odd one, slipped free, is returned for its treason. This consignment to the cultural ash heap of such familiar - and, for Sant, defining and sustaining - items deepens his estrangement from things as they once were. His awareness of the rapidity with which memories, rendered here as barely regarded albums, are left behind, lends his sober nostalgia a particularly hard edge. Personal history resembles not some carefully kept archive but the odd mementos that shake loose from a former time dimly recalled. Indeed, nostalgia itself - the effort to repossess the past - is for Sant a losing battle. ‘We court orderliness yet find lithe process / befriends us’, he explains in ‘Late Summer Passages’, a poem that renders everyday objects as ‘the playthings of vertiginous change’. Similarly caught between a past tenuously held and an insistent future is ‘Climate’: I

invoke spring garden’s motto: transform or whither,

though the house with its elderly furniture and photographs would have it otherwise and pardons reflection. Yet gardens are continuance... Hie poem, which discovers the speaker puttering among the clematis and ivy, counters the season’s harsh dictum to modify or die with a tentative acceptance of impermanence as embodied by the ‘magnified spaces’ that ‘the windblown backdoor opens onto with its comings and goings’. Nature has perennially provided poets with a trope for change, and while Sant, thankfully, cannot be mistaken for a ‘nature poet,’ he capably employs images of the natural world in working out the drama between stasis and mutability. Nowhere does Sant elucidate more fully this often violent dynamic than in ‘To the Sea’: Here

is a headland, there the bay

you, great cartographer, have made and which won’t be ripped free of my hands in the wind; your pride the monumental permanence of cliffs though all your meditations turn to sand. How I love your movements: whorls and rips; the waves called by the loyal moon, or fluid forces that boggle cities. Sant’s acceptance of fluidity here is as restless, one might almost say as volatile, as the force of change itself. The poet makes his home in the ‘whorls and rips’ of perpetual motion. In this vein, questions of home - which Sant finds not by a quiet hearth but in a constantly shifting world - recur throughout the collection. ‘Long Distance’, in which a dial tone simulates proximity, explores the problem telephonically: ...Now

the voices come clear, oh so

recently close, it seems ear rests on ear to show distance has thinned, time zones twinned... or just that home is all places to the telephone with its fluent and garrulous dial tone. That home exists not in one place but in ‘all places’ is for Sant both a hard fact and a useful realization through which to make life more habitable. Not surprisingly for a poet, it is words that serve finally as a stabilizing influence, fixing with a name what might otherwise slip soundlessly away, as in ‘An Australian Visits the Future’: Language,

I find, is home. Old holograms in shops

recall it: streets with Anglo-Saxon names, a new brick suburb anxious for trees, people in cars who greased their pleasure in distance. In his clear-eyed views of harsh uprootedness, Sant manages to take a melancholy ‘pleasure in distance’, which, for the geographically dispossessed, can be one way through to the sustaining domesticity which we all need to survive. Australian Verse: Triumphs And Inanities Album of Domestic Exiles Brian Henry PN Review, No. 127, Vol. 25(5), May 1999 Like Forbes [Damaged Glamour], Andrew Sant writes intellectually compelling and formally taut poems that deftly wed structure to subject matter. The poems in his fifth collection, Album of Domestic Exiles, offer a skilfully ‘controlled abundance’, and invite and sustain repeated readings. As the book’s title suggests, Sant is interested in the psychological and emotional effects of various types of exile, as in the work of Elizabeth Bishop, whose poetry Sant’s more than superficially resembles. And because he does not allow himself to become complacent with language, he manages to avoid the quotidian quagmire in which most domestic poets become trapped. The book’s title sequence consists of eight short poems focusing on objects exiled from domestic use - LPs, candles, black-and-white snapshots, Mussolini’s umbrella. Sant considers the poignancy of being perpetually unsettled rather than the pathos of it (political exile is absent in this collection, which, after all, is an ‘album of domestic exiles’). This angle brings the poems closer to individual experience while avoiding sentimentality, convenient expressions of emotion, and hackneyed language, so that Sant surfaces with personal poems of universal import. In his examinations of exile, Sant illuminates the experience of displacement in numerous poems - ‘Haute Locale’, his mock ode to the United States, that ‘generous ally, home of the free / cliché’; ‘Elegy for the Queen’s Head’ (‘Let’s face it, since she’s licked, / ...The rest’s expressly philatelic’); and the more serious ‘Voyage’, a dramatic monologue about ‘Britain’s child migration scheme’, a euphemism for the export of unwanted children. Although Sant is serious about exile, he is devoted above all to his art: when ‘everything is leaving’, ‘language, I find, is home’. This preoccupation with language is manifest throughout the collection. Sant’s well-turned lines advance an often-complex syntax that enhances the rhythms of his poetry. ‘Tactic’, a 36-line poem consisting of two sentences, never strains under the syntactical manoeuvres that keep the poem moving; and ‘Profit and Loss’ is well-controlled and lyrical:

the accounts are windswept;

where memos flew, gulls blessed with subatomic guile encounter walls that are not there, swoop through and up beyond the roof, a perch of air; the absent- minded managers, sportsmen all, have blown their cover and can’t be seen though it’s still early afternoon... Sant’s best poems demonstrate Bishop’s low-key yet scrupulous style; and like Bishop, Sant seems equally comfortable in traditional forms and in a contemporary vers libéré (freed verse), as opposed to the lineated prose many poets call free verse. Sant’s rich verbal layers and cadences are almost always compelling, and many of these poems reveal the ‘whorls and rips’ made possible when an exceptional facility with language collides with everyday subjects. Poetry - Three poets and fifty years of Australian poetry Album of Domestic Exiles Julian Croft Antipodes, Vol. 12, No. 2, December 1998 This is an unusual selection of current poetry books to review. Two of the three [David Rowbotham, The Ebony Gates, Val Vallis, Songs of the East Coast] are partly collections of poems written in the 1940s, supplemented by poems written in later decades. The remaining one is a selection of recent verse by an established poet in mid-career. It is hard to read them without reflecting on the differences fifty years have made to Australian poetry... Coming to Andrew Sant’s latest book, Album of Domestic Exiles, the reader feels like the states invoked in the title poem: the comforting familiarity of the domestic, but the attendant dislocation, unease, and uncertainty of exile. That, I imagine, is the state of the ego in any poem these days, either as reader or writer. In fact, the title poem sequence ends with a poem addressed to the reader in which the writer competes with the reader to be a reader too: Look,

a

book must belittle a DINK

when it replaces a condom - won’t you rise and circulate now as a breeder? Give those pages the brush-off. Let me too be a reader. ‘Absent Third Party’ And there you have the difference between a poet of the present generation and those of the previous one. The transparent page, which was there as a conduit for voice from poet to audience, has become a mirror, partly silvered, which lets both sides of the poem leak one into the other. But we might note, there is an absent third party, which the rest of the poem tells us is creativity or the life-force. Sant’s poetry is witty, stylistically difficult in places, urbane, pleasant, deep but whimsical. Not unexpectedly, the playfulness of the poetry often obscures the subjective centre of the poem. This is not a bad thing, for it gives the poetry a slippery, shining elusiveness that challenges readers to give the game of reading their total commitment. It is intriguing that place is so central to each of these poets from different periods. All of them range through the world, yet locate the subjectivity of the poet in a distinct Australian region. In Sant’s case, this is Tasmania, but, as one would expect of a poet in the late twentieth century, that place is not a point, as it is for the earlier poets, but a field, fuzzy, subjective, and open to influence from other points. Style then might be an expression of that same difference. For the earlier poets a declamatory certainty, a rhetoric of persuasion, and for the later poet, the reflexive suggestion, thc whimsical invitation, a rhetoric of collaboration. Antipodean Voices - Album of Domestic Exiles John Knight Social Alternatives, Vol.17, No.3, July 1998 Album of Domestic Exiles strikes a wry dry note from the start. [...] Sant’s verse is clever, polished, subtle, dry and sometimes a little too subdued or restrained for my taste. Yet on a second or third reading its quality is undiminished and new aspects revealed. Befitting the book’s title, his poems range the globe: NZ, India, USA, England, Bali... Four great poets [50-50 by Pam Brown, Dividing the Light by John Allison, Both Roads Taken by John Allison, Living in the Shade of Nothing Solid by Jeff Guess], five brave publishers. This most minor poet, editor and boutique publisher salutes you. You deserve much greater audiences than you receive. The Genius of the Reader (or Who’s sitting on the chair?) Album of Domestic Exiles Bev Braune Southerly, Vol. 58, No. 2, Winter 1998 Let

me too be a reader

In Album of Domestic Exiles Andrew Sant openly asks to be considered a reader of worlds ‘claimed or copied or constructively made afresh’ (‘Profit and Loss’) even though his ‘chair in the room’ might be concealed by ‘a drunken / fence’ (‘Tactic’). Here ‘might big questions arise again’ (‘Taking My Daughter to the Cave’) where we may participate in ‘the slow / digestion of this place’ (‘A Painter in Paradise’). He reads ‘whatever tricks the light proposes’. It is

acres between atoms, magnified spaces

the windblown backdoor opens onto with its coinings and goings. ‘Climate’ Drafts of air turn the leaves of his book. He moves from the static - the taxidermist of the ‘vivid block’ of ‘adverse weathers’, of ‘meetings with archaeology’ - to the regeneration of images - gardens and due ripening, glass, lights, flames, matched flints reaching from his earlier book Brushing the Dark where a single ‘match flares’. In Album of Domestic Exiles he has travelled deeper into soil and beneath doors. He shifts back and forth from the last century to one in the far future. His is a world of cameras, shutters and exotic heights. He draws us in with the music of subtle and effective internal rhyme, assonance and end rhyme, carrying metaphors with grace through individual poems and the entire collection. Sant’s care in understanding his position as the reader’s reader is a marked characteristic of his work. It is a position with which he opened his first collection, Lives, with ‘Glenlyon’: ‘let these passing words settle on the unmapped page’. ‘So much must be pared down to this: / whale bone, crow’s skull, fossils’, he reminded us in The Flower Industry. In his latest volume the way to the objects in the poem and the objective of writing poetry are largely bound by disruptive winds where ‘sunlight strives to eclipse the best gift’. His markers are precise and distinct, particularly in two beautifully sustained series, ‘Late Summer Passages’ and ‘An Album of Domestic Exiles’, where he is ‘the sanguine invader [who] blows fuses and darkness confides’. Mr Lawrence and Dr Sant - Album of Domestic Exiles Simon Patton Island, No. 75, Winter 1988 Like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the work of Andrew Sant and Anthony Lawrence [Skinned By Light, New and Selected Poems] represents two contrasting personalities within a complex psyche - in this case that of contemporary Australian poetry. Sant’s writing displays a certain gaiety of disposition: it is urbane, metaphysical, sedentary; Lawrence’s wears a more than commonly grave countenance: darkly pastoral, hallucinatory, itinerant. Yet aspects of their poetry overlap. Both base their poetry in the world of experience and tend to subordinate nature to culture, swearing allegiance to ‘personality’ as the source and objective of the poetic. Thus, despite their many differences in motivation, their two poetries are consistent in the way they value the transformation of reality through language over what Eliot described as transparency: ‘poetry so transparent that we should not see the poetry, but that which we are meant to see through the poetry’. The cover of Andrew Sant’s latest collection - Album of Domestic Exiles - features a black-and-white snapshot of a young boy. This one image effectively suggests two distinct yet complementary aspects of his writing. Most obviously, it makes a direct reference to poetry as photography, the ‘writing of light’ that is able to capture the flux of the present moment for posterity. Secondly, it suggests that dimension which coincides with historiography - poetry as a means with which to interpret and to reanimate that which has already happened (an impulse that is not always free from a decadent nostalgia). Of these two poetries, Sant expends most of his talent on photography, the black-on-white of poetic transcription. Many of his titles serve as captions to the scenes he has caught in language. Despite this orientation, Sant is not essentially a word-portraitist; his vision is cerebral. The majority of poems in Album are animated not by any proliferation of visual detail but by wit: For

company, each other. Monkish these stooped willows

huddled around the dam are guests when, at dusk, the rest of the party has fled; guzzlers like their mates whose reflections all day brisk rivers have trawled; experts when the diviner discovers in the forked switch he’s grasping a seizure from water like lightning. ‘Willows’ What counts here is not photographic accuracy but the ability to transpose nature into metaphors drawn from an all too human world. The willow trees are quickly displaced by a population of monks, guests, mates, experts, diviners. I think you could argue that Sant does not see the willows at all in their particularity. Instead, they are perceived only insofar as they act as a trigger for a series of related meanings. Throughout Sant’s Album, the line of inspiration leads almost exclusively from the natural to the cultural: tortoises ‘swagger / as if pissed’; timber recalls ‘wine deepening / its flavour in a cellar’; red poppies ‘brazen out their lateness’. In other words, the poet projects human qualities onto nature, taming its fundamental otherness in an effort that could be called ‘civilising’. It is this insistence on the human that inspires Sant’s poems on social artefacts, the ‘domestic exiles’ of his title. In these texts objects of frozen history become the pretext for a punning anthropology: If

music hadn’t stunned them

they’d be less upright and orderly, confounded by the echolalia of usurpers: and slipping free of the rack, welcome a spin away from Coventry. ‘LPs’ If Sant fixes the moment with his wit, Lawrence does so with his exuberant fantasy... Ingenuity is a mixed blessing for both these poets. Sant, in particular, is capable of a difficult intricacy, a feature aggravated by his fondness for syntactic inversions, archaic vocabulary, and double-entendres. Where he is comprehensible he can be charming, but elsewhere his density verges on convolution - ‘Let’s face it, since she’s licked, / the dial of HRH corresponded with a need for absent mates / who stuck to their posts. The rest’s expressly philatelic’ (‘Elegy for the Queen’s Head’). Lawrence on the whole sticks to colloquial diction and thereby avoids syntactic tangle. His imagistic richness does make for opacity, but he is capable of great inventiveness in his use of new angles to probe familiar situations (poems such as ‘Genealogy’, ‘Retirement’, and ‘Reversals’). Both Sant and Lawrence take their stand on the ‘I’ to write poetry expressive of their views of the world. But this stepping back into personality produces a literature of separation in which the human projects its private meanings onto the natural. The American poet Robert Creely offers an alternative, oracular model: ‘I am more interested, at present, in what is givcn to me to write apart from what I might intend. I have never explicitly known - before writing - what it was that I would say.’ It is precisely this unknown quantity that I missed in the work of his Australian counterparts. Sustained by a strong sense of self, their poetry resists the tug of more experimental agencies. Album of Domestic Exiles Louise Oxley Famous Reporter, No. 17, June 1998 This volume, Andrew Sant’s fifth and his first for nearly nine years, confirms him as a poet of unusual intelligence and skill. As the title indicates, the poems are linked by the overarching theme of exile, but it would be simplistic to dismiss them as only about this. In his hands exile has many facets. The subjects of his scrutiny are exiled in time, as well as physical and mental space. And the range is broad, encompassing both the natural and man-made worlds: gardens, caves and forests, journeys, animals (domestic and otherwise), everyday artefacts. All are observed so minutely as to reveal a hitherto hidden, and often quirky, aspect of their existence. These are reflections on visits to England from Tasmania, and to places, notably Indonesia, in between. Through the poems Sant explores what it means to live in the shadow (or perhaps the light?) of one’s birthplace. Reading ‘Shifting Furniture’ I am reminded of a comment made by critic Andrew Riemer, another child migrant, that ‘I am always conscious that my living here was the product of a decision made on my behalf’ (Canberra Times, 9 May 1998). Sant examines dis-junction and con-junction, dis-location and co-location, the fact of living with ‘Familiar unfamiliar signs’ (‘Typhoon’). Predominantly intellectual rather than emotional, the poems are characterised by a mood, not of detachment exactly, but of emotional restraint. In spite of the fact that many centre on family relationships and close friendships, there is the sense of a distance placed deliberately between the poet and his subject-matter. They are indeed considered poems, experience magnified by rational hindsight. Change, renewal and the oddity of scale are major preoccupations in these poems. Sant’s mastery of metaphor renders it unobtrusive; he manages to do away with the now-naturalised metaphor of the future as forward and the past as back or behind, conflating the temporal with the spatial. In this way he probes our complex relationships with history and with home. He hopes, for example, that his parents’ furniture will end up ‘disencumbered by the decades removed from the eyes of my daughters’ (‘Shifting Furniture’), and discovers ‘a hole surprised by loggers / toppling the future one afternoon’ (Taking my Daughter to the Cave’). It is in lines like these where he is at his most skillful; in the latter example the coupling of the casual language with an event of such moment makes it all the more appalling. For the most part, however, the poems are suffused with good humour, with a largesse which equally accommodates the earthy and the elevated. There is an obvious love of wit, both as admired in others, (as in ‘Vocal’), and as exercised by the poet himself, (as in the playful ‘Blotter’ and ‘Elegy for the Queen’s Head’). The conversational tone of the poems is deceptive, however. They can be so linguistically loaded that the reader is pulled up short by a dense line, often the last. Very occasionally, this doesn’t quite come off, in the last lines of ‘LPs’, for example: Exile’s

an

eclipsed disc parade

when a die-hard fad’s sacked. This seems to me to be just too tightly packed for comfort, positively tongue-twisting when read aloud. I wonder whether in these cases the idea isn’t being strangled. Otherwise there is very little that jars. Technically the poems are conservative - painstakingly constructed and carried by assured rhythms. His sense of irony and ear for the colloquial ensure that the tone is never pompous. In every poem there’s something to delight, the senses apprehended with novel acuity, a surprise, a felicitous image: ‘the slouched shed and delinquent fence’ (‘In the Garden’) and ‘the garden fork holding the soil in its place / like an hors d’oeuvre’ (‘Days of Incompletion’). These are sharp, refractory poems. They glint obliquely. There is much to be discovered here, but concentration is needed to bring them into focus. I have to admit that I didn’t warm to them immediately, but I have discovered that this is because they are poems which require - and reward - reading and re-reading. The best kind. Waiting for the Lights to Change - Album of Domestic Exiles John Foulcher Overland, No.152, Spring 1998 In his book The Great Divorce C.S. Lewis tells of a dying man sitting under a tree in a meadow: he is becoming impatient to die, knowing that he will soon be in paradise. Finally, death comes, and he wakes excitedly, only to find he is sitting under the same tree in the same meadow. Just as disappointment is starting to descend, he touches the grass and finds that it feels and looks more like grass, like the essence of grass, than he has ever known. It’s the same with the tree, the sky, the clouds. Looking around, he realizes that he is indeed in paradise; in fact, he always had been there, but he had simply failed to notice. The point of the story is obvious: paradise is in the detail that constantly surrounds us, but we don’t see the eternities in our grains of sand. It’s not surprising the aim of a great deal of poetry is to explore the daily detail which catches life’s meaning and delight. Each of these books, in its own way, deals with this concern, and each provides moments where the mundane is elevated and transcended... It’s been almost a decade since Andrew Sant’s last collection, Brushing the Dark. His new volume, Album of Domestic Exiles, shows the meticulousness of poetry a long time in the making. From the opening lines of the book’s first poem, ‘Climate’, Sant’s impressive sense of language and line is clear: A

jasmine spreads its scent into the humid air,

the white flowers whirr like propellers for a few days and there are more and more, and a clamour of bees that have sped beyond winter: everything is leaving. Unlike Kinross-Smith [If I Abscond, New Poetry and Short Fiction], Sant handles a variety of forms with ease, poems either tumbling down the page in short lines (‘LPs’) or spreading elegantly in long rhythmical units (‘Willows’). More than the other poets reviewed here [Jennifer Strauss, Tierra del Fuego, New and Selected Poems, Connie Barber, Enter Your House with Care, Joyce Lee, The Whispering Ear], Sant finely observes the small detail of individual lives. He lives in a paradise of ordinary things: garden rituals, domestic procedures, furniture, umbrellas, old records and so on are all explored with excitement and so are lifted into themselves. Occasionally, though, I’m left with the impression that Sant’s facility with language disguises a lack of substance, that the weaker poems don’t transcend their detail - the title sequence may be a case in point. Sometimes, an urgency is lacking in them. Sant is a better craftsman than Kinross-Smith, but occasionally could do with the latter’s intensity, his economy. Overall, though, both poets’ collections demonstrate the virtues of infrequent publication. Domestic Poets - Album of Domestic Exiles Brian Henry Australian Book Review, No. 198, February-March 1998 Both Dennis Haskell [The Ghost Names Sing] and Andrew Sant are primarily domestic poets. Family and friends comprise the milieu of many of their poems, which attempt to transform quotidiana into something of enduring interest. The chief danger of this type of poetry is that the prevalence of so many poems about family members and friends results in a poetic environment that can resemble a vast, monotonous suburb. If most domestic poets seem indistinguishable from each other in their subject matter alone, then the situation of contemporary poetry becomes further muddled when this homogeneity is bolstered by a general complacency with language. Andrew Sant, on the other hand, writes intellectually and linguistically compelling poems that deftly wed structure to subject matter. The poems in his fifth collection, Album of Domestic Exiles, offer a skilfully ‘controlled abundance’ and invite and sustain repeated readings. As the book’s title suggests, Sant is interested in the psychological and emotional effects of various types of exile, as in the work of Elizabeth Bishop, whose poetry Sant’s more than superficially resembles. The book’s title sequence consists of eight short poems focusing on objects exiled from domestic use - LPs, candles, black-and-white snapshots, Mussolini’s umbrella. Sant considers the poignancy of feeling perpetually unsettled rather than the pathos of it (political exile is absent in this collection, which, after all, is an ‘album of domestic exiles’). This angle brings the poems closer to individual experience while avoiding sentimentality, convenient expressions of emotion, and hackneyed language, so that Sant surfaces with personal poems of universal import. In his examinations of exile, Sant illuminates the experience of dispalacement in numerous poems - ‘Haute Locale’, his mock ode to the United States, that ‘generous ally, home of the free / cliché’; ‘Elegy for the Queen’s Head’ (‘Let’s face it, since she’s licked, /...The rest’s expressly philatelic.’); and the more serious ‘Voyage’, a dramatic monologue about ‘Britain’s child migration scheme’, a euphemism for the export of unwanted children. Although Sant is serious about exile, he is devoted above all to his art: when ‘everything is leaving’, ‘Language, I find, is home.’ This preoccupation with language is manifest throughout the collection. Sant’s well-turned lines advance an often-complex syntax that enhances the rhythms of his poetry. ‘Tactic’, a thirty-six-line poem consisting of two sentences, never strains under the syntactical manoeuvres that keep the poem moving; and ‘Profit and Loss’ is admirably textured yet lyrical:

the accounts are windswept;

where memosflew, gulls blessed with subatomic guile encounter walls that are not there, swoop through and up beyond the roof, a perch of air; the absent- minded managers, sportsmen all, have blown their cover ...and can’t be seen though it’s still early afternoon, Sant’s best poems demonstrate... low-key yet scrupulous style; and... Sant seems equally comfortable in traditional forms and in a contemporary verse libéré (freed verse), as opposed to the prose hacked into lines that many poets call free verse. Sant’s rich verbal layers and cadences are almost always compelling, and many of these poems reveal the ‘whorls and rips’ made possible when an exceptional facility with language collides with everyday subjects. Human side to imperial policies - Album of Domestic Exiles Edward Reilly Geelong Advertiser, 17 January 1998 Closely watched, our familiars. Andrew Sant is one of those careful, observant writers for whom the world is to be read as one would examine a painting or a printed text, and above all, he likes what he sees. In reading through this book, I was struck at the domesticity of his subjects and the close familiarity with which Sant talks about a diverse range of subject matter - tortoises and hedgehogs, assorted pets, family, eating strawberries - but also with his willingness to tackle major subjects. In ‘Voyage’ Sant uses his experience as an immigrant from England to explore the loneliness and feelings of abandonment of a group of young English boys sent out to Australia. Some of them must have landed in Adelaide, for in my schooldays there were batches of boys who were ushered into the classroom looking lost and spoke quite strangely. Perhaps it was the first time we had heard English as spoken by the English. They could play cricket quite well, preferred soccer or rugby to real football, and were given rice pudding - ‘to make them feel at home’ - explained the cook. The last batch ever of childish migrants, England’s unwanted, left Southampton as late as 1967 as part of the child migration scheme which had its origins as far back as 1618 when a group of destitute children were shipped off to Virginia to fill ‘the empty Empire’. Sant recognises the cruelty of imperialist policies in effect: these children were ‘farm hands, at first, last coinage, imperial investments spent’ - in which human lives had become expendable items in some vast geopolitical game. The real cost in human terms were the unrecoverables - self-respect, misplaced parents, ‘lost years’. Of all the poems in this collection, my favourite is ‘The Pendants’. What one may call ‘a forest’ another will name as ‘woods’: is this just a difference in local dialect? I doubt it. Even the light changes when we cross over from the mainland to Tasmania, and changes even more so when we make the voyage back to Europe. Saint uses these differences to investigate how changeable our language becomes at such removes of time and place. On a lighter note, sequences ‘Late Summer Passages’ and ‘Album of Domestic Exiles’ extol the very ordinary and wonderful things we do in our daily lives, climbing ladders to ‘an exotic height’, visiting a Church, celebrating a birthday and lost and banished household items. Each is an occasion for celebration of detail and wry comment of life’s little absurdities. Sant’s skill with language and verse-form are evident throughout the collection. He offers the reader polished sonnets, blank verse and extended poems. Andrew Sant lives and teaches in Tasmania and has been a distinguished co-editor of Island, Tasmania’s foremost literary magazine, and a writer with an Australian and overseas reputation. This collection of poems builds upon his previous works begun with Lives (1980) and continued through to the memorable Brushing the Dark (1989). I especially would like to remark on the production of this collection by Black Pepper, the North Fitzroy publishing house which is building up an enviable list of modestly priced and well presented publications by interesting Australian writers. With the withdrawal of many of the major publishing houses from publication of new poetry and fiction, and the hardening of distribution channels for independent writers, Black Pepper’s enterprise should be encouraged by the reading public. Our good writers like Andrew Sant deserve to have their voices heard, their works read as widely as possible. In Geelong, Album of Domestic Exiles and other publications by Black Pepper are stocked by, or can be ordered from, local bookshops. Exiles In Heart And Mind - Album of Domestic Exiles Andrew McCue Ulitarra, No. 14, 1998 Same publisher, same theme of exile, even similar allusion to photography in the titles, but Andrew Sant’s Album of Domestic Exiles and Mammad Aidani’s A Picture Out Of Frame are two very different books. Black Pepper obviously knows what is the spice of life. In the Album, Andrew Sant is often as missing from his work as are photographers from theirs. It’s hard to get to know him, even when he appears to be revealing his childhood to you. When you get a glimpse of him in what seem to be some of his self-reflections, he’s usually got the camera in front of his face. Then I read this: Care,

detachment, a framed deletion

of words called from a distance, and clearly a background gentled like haze. ‘Ah!’ I said to myself, ‘He’s more interested in a photographer’s eye than he is in the writer’s ‘I’ and his favourite subject turns out to be ‘a background gentled like haze.’ This is an easy enough aesthetic to pull off if you’re a photographer (and many a centrefold in Penthouse has been pulled off in the same way). All you do is focus upon some quirky, domestic object in the foreground, so that your naked subject is ghosted into the background where it can to stick to itself (and many a centrefold does this, too). And if you are an ‘exile’, backgrounds are pretty bloody important to you. I bet you, for example, that if Sant were to take a identifying dial could be pleasingly ‘gentled like haze’ beyond recognition. Admit it; you’d love it. Nevertheless, Sant manages to do it with words which is no mean feat, given that it is the nature of a words in poetry to argue for the spotlight. In the aptly (if not lyrically) named Album of Domestic Exiles, Sant applies the same backgrounding technique to a number of subjects. We get, for example, the exile’s experience of his ‘adopted street’ via a focus on a fruit stall; or a sense of traversing oceans and deserts by foregrounding a dial tone; or a discourse ‘on the fascism of Mussolini via a back-lit umbrella. One poem, titled ‘The Mineral Boom’ turns out to be a nostalgic and cleverly boyish portrait of a teacher in school. Indeed there is no subject, no memory, no theme which does not hang like an arras - gently exiled to the background haze - behind Sant’s still-life arrangements of some domestic or garden object. This may sound critical, but it mostly works. Backgrounds are obviously important to an exile, and Sant seems determined to perfect the roving, idiosyncratic eye of the perfect stranger. Your background marks the spot where you are both rooted and uprooted. You inherit the Cherry Orchard, but have lost the recipe for cherry preserve. ‘Living is a knack’ writes Sant; ‘It’s handed down like an axe that cannot fell the family tree’ while your mental larder can end up jam-packed with unused labels. The ample lexicon of Sant’s Album mainly produces black and white stills - he has little time for colour and movement. He is an intellectual poet. Line and form are his chief aesthetic concerns. At a glance he may seem to offer you an abstract art. But you need to spend some time with him - join the dots and paint over the numbers - the abstractions will take root, and the backgrounds will come to the fore. If some of those French theorists are right, and thinking is always and already a form of exile, then Sant’s poetry is about as intelligent as it gets. If you take your hat off to Sant for giving you the exile’s natural, if cool-heeled intelligence, you eat it for what Mammad Aidani can do with banishment’s blistering heart. Neatly, for the conceit of this review, Sant’s finale is this: ‘Write! And make exile / unite with the reach of a table’. Mammad Aidani’s short novel starts out with a man at a table doing this. ‘What kind of world are we living in?’, he asks himself looking into the distance of his memories. He feels the exhilaration of his strong desires and hopes for a better future. Album of Domestic Exiles Richard Hillman Sidewalk, No. 1, 1988 The poetry in Andrew Sant’s Album Of Domestic Exiles compares with Bertolt Brecht’s satirical poetry, perhaps not in content, but in its childlike though poignant construction of detail. Sant is a playful and elegant poet. His use of the vulgar comes with a set of stage instructions while off-stage you can hear someone urging, ‘once more, with feeling’. His poems appear in-progress, caught out during rehearsal (as if by accident), but wanting to leave early they rush over things, perhaps an encounter, missing the mark, or cue, unable to be called back to do it again. Like a child practising a magic trick, Sant is a privileged illusionist who must impress his captive audience with a flare for the obvious. Exiles pretends to be a geo-historic lesson in retrievability but recited with the short-cut tempo of an actor full of his own self-worth. | |||||||||