|

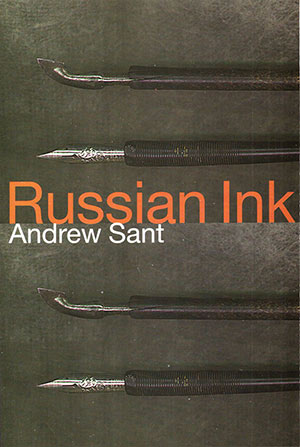

Russian Ink : Andrew Sant |

||||||||

Book Description ...trust

me,

a

swatted fly knows

the cry of

Neighbourhood Watch

and gravity tots up the cost when an apple drops. Like the KGB, the poems

in Russian

Ink work beneath respectable surfaces. In his expansive

new

collection, Andrew Sant’s language is often charged with wit,

and is

always incisive. There’s characteristic playfulness in

‘Anthony Sant’,

a comic take on Graham Greene’s unpublished first novel, and

in a

vibrant series featuring the folkloric Green Man on a contemporary

mission. But beneath surface detail there are powerful, controlled

emotions. His ‘Stories of My Father’ is like

Turgenev on holidays.

Above all, these are enjoyable poems, rich in imaginative diversity.

Andrew

Sant is a craftsman who is not

afraid to take risks with language and themes. This book is a major

work by an important, innovative poet.

Anthony

Lawrence, The Mercury

Among the poets playing the more traditional tunes, Andrew Sant is the best of those new to this reviewer. Conor

O’Callaghan, The

Times Literary Supplement

Andrew Sant writes intellectually and linguistically compelling poems... made possible when an exceptional facility with language collides with everyday subjects. Brian Henry, Australian Book Review ISBN 1876044349 Published 2001 112 pgs $25.95 |

|||||||||

Book Sample

Reviews

Two Very Different ‘Melbourne’ Dreamings Melbourne Elegies, Bread, Russian Ink, The Dining Car Scene Brian Edwards Mattoid, No. 55, 2006 .......Andrew Sant’s Russian

Ink is a generous collection that offers

accessibility with edginess. Most typically, these are poems about

‘everyday’ experience; but, as should be the case,

this is the everyday

reconceived astutely and anew such that recognitions of the familiar

include, simultaneously, those necessary factors (at least for writers)

of particularity and difference. The sense of contexts that include and

exceed the local is implicit in the book’s title which comes

from the

opening poem, ‘Nightfall,’ where a string of

metaphors evokes the

coming of darkness and leads to the final lines: ‘Then try

repeating

/ Dark clouds over Siberia’ / and ‘I write with

Russian ink’.’

Here

there are poems about experiences of travel, parting, family, ailments,

showering, holidays, a snake catcher, moths and carpentry. But

‘Moths,’

for example, moves in its five parts from the bemused description of

moths beside the home front door to childhood memories of a man who

captured specimens, the names of planes, Darwin in Brazilian forests,

and to such imaginative projections as:

There’s change in any event -

the moths are testing the binary stakes, ranging from dark toward light, a scattered archipelago, at rest, here, weightless as images gleaned from a book.

As

they linger in drawers and, with butterflies, in taxonomies,

collections, forest ways and the imagination, moths can provoke poetry.

Similarly, rituals of showering include an image of Juliet Binoche, a

pun on Eliot’s ‘falls the Shadow,’

details of plumbing and decor, a

play on Heraclitus, and luxury of waterflow.

Interspersed with short poems notable for their precise use of language and the dexterity of their formal arrangements, there are longer sequences: ‘Anthony Sant’ with its attention to texts, publication, Graham Greene and the vagaries of literary history; ‘Stories of My Father’ which presents a fine litany of detail around ‘I just wanted to get him off my back. / Now it’s the certain weight I lack;’ ‘Indian Pacific’ and the intermingling of specificities of journey and dream; ‘All We Know’ as a variable exploration of neighbours and the limitations (and temptations) of knowing; and the tight-checking sonnets of ‘Belli’s Shade’ which evoke images of Giuseppe Belli, Rome, a conference, sexuality and a relationship. In addition, there are the Green Man Poems, fourteen of them, that update the mythical figure, setting him loose upon the world as a sort of flaneur of the imagination, and ‘Summertime: A Holiday Chronicle’ which presents the cleverly conceived narrative of Jim and Wendy and the boys, with sundry doubts, clues, shifts, discoveries and, it seems, a happy ending. ...These are interesting collections. Black Pepper continues to present writing that warrants attention. Russian Ink Nicolette Stasko Southerly, Vol. 62, No.1, 2002 In China, porcelain is

defined as

‘pottery that is resonant when struck; in the west, a

material

that is translucent when held to the light’. It is, of

course,

easily chipped and equally breakable. One could say this is also a

plausible description of good poetry and one which applies to the

following three collections [Diana Bridge, Porcelain, Gig

Ryan, Heroic Money,

Andrew Sant, Russian Ink]...

...from Black Pepper, another very handsome production is Russian Ink by Andrew Sant. In other respects, however, and although Bridge and Sant share a certain wordly knowledge and erudition, these two poets could hardly be less alike. While the poems in Porcelain are meditative and elegiac, concentrating on the past, those in Russian Ink are very much in the present tense - audacious, romping through ordinary life as observed from a train window, seen over the road or heard next door: ‘...trust me, / a swatted fly knows the cry of Neighbourhood Watch / and gravity tots up the cost when an apple drops’ (‘All We Know’). The poems are witty, acerbic and intelligent. Even the elegy ‘Stories of My Father’, remains poised on the edge, equally willing to see the absurdity and imperfection of human beings and their relationships, as well as the sadness and fraility of existence: I’ll never get it

straight, or wish to.

There’ll not be his Scotch to intercede. I am the sole beneficiary. Although occasionally

perhaps too

clever, rarely does Sant’s humour overstep the mark by being

judgemental or smug. He just as often turns the magnifying glass on

himself - as in what the cover blurb describes as his ‘comic

take

on Graham Greene’s unpublished novel Anthony Sant’:

Of readers or critics

I relinquish my need; leave ‘Sant’ to the reams of that poet. Russian Ink is a rich collection replete with - there seems no other word for it - muscular verse which dances through the pages. I particularly enjoyed the satiric narrative ‘Summertime’ with its paranoid male characters, just for the sheer playfulness. Sant’s ability with rhyme is unusual in contemporary poetry and almost always subtle and surprising. But it would be unfair to leave the impression that Russian Ink is only entertaining: there are many poems of substance and feeling: ‘If now I could grasp the source / of this darkness when the sky is bright’ (‘Down from Mars’); ‘I’m recalling now since memory / comes increasingly to seem / a habitation’ (‘Moths’). The book, however, is simply too long. This reader at least, could have done without the ‘Green Man Poems’ in particular, which, while inventive and sometimes interesting, stretch the theme beyond its limits. Changing our way of seeing Anthony Lawrence (poet) The Sunday Tasmanian, December 28 Album

of Domestic Exiles appears at a critical time in the

publishing

of Australian poetry. Black Pepper is one of two or three publishers

committed to continuing what most mainstream houses see as a financial

drop in the bucket. Of course, anyone who knows anything about the

genre understands that finance is not concomitant with the writing and

publishing of poetry. Black Pepper is a floodlight in the gloom, and

they have an outstanding catalogue.

Andrew Sant’s fifth collection, like its cover, is sharp-edged, yet draws you in. We see an aging photo of a small boy wearing a fighter pilot’s helmet. An oxygen mask hangs down like some terrible growth under his chin. He is gazing off into the distance while standing against a backdrop of suburban security. It’s a key to the collection, which can be read as one long poem, or seen as a series of connections. Sant has crafted past, present and future into a book that is, while not totally seamless, a map that unfolds by itself as you read. ‘Climate’ is the perfect opening poem. It lays the foundations for many of the book’s concerns: loss and replenishment, pure observation (through memory and immediacy) and the poet’s sense of his own life and death; of how an acceptance of this balance is essential for growth. Take these examples from the last two stanzas: continuance, co-operative death, interdependence, comings and goings. Having sampled the dislocation, here’s unity: ...a

round seven years it takes

for the all-change of my body’s cells and ...a

clamour of bees

that have sped beyond winter: everything is leaving Reading back and forth through this book, I had a sense of someone mapping presence and absence, despair and exhilaration: a curious cartography of the mind and body. It works. You don’t need a compass. Sant’s fine sense of craft and his ability to change our way of seeing are directions enough. Often, he uses tight rhythms in long-limbed, narrative pieces like ‘Mainstreet Fruiterer’ or ‘The Pleasure Seekers’. Though, even here, there is a lyricism that works on the inner ear as the stories unfold. ‘The Pleasure Seekers’ has echoes of Paul Muldoon, that Irish shape-changer, and the American poet August Kleinzahler. Take the last two lines: Dark

eyes watch them stalking

shadow-like across wilted offerings

that might be refuse, towards the insomniac, throbbing bars. The brilliant ‘Elegy for the Queen’s Head’ reveals how Sant can align black humour and history to create a common, local experience. I’m amazed that a poem about a postage stamp can be so unsettling: Never

in miniature did she flinch

or shake the tiny sparklers at her throat… ‘Voyage’, while being the most prescriptive of the poems concerning exile, is a poignant diary of internal/external conflict in a new land. It’s like a talk-back program about identity coming and going on the wind until, when you’re close enough to hear every word, a gallery of lives and stories come through indelibly. Album of Domestic Exiles is a book that works on many levels: as a whole, and within each poem. Andrew Sant is a craftsman who is not afraid to take risks with language and themes. This book is a major work by an important, innovative poet. When the shape is everything Gig Ryan The Age, 23 June 2001 Russian

Ink is Andrew Sant’s sixth book. His work is

always consistent,

but Sant’s strengths and weaknesses do not change from book

to book and

again there are stray endings preceded by a sudden formality or

ominousness, striking images lost in a sea of unevenness (‘At

his

wrists / his sleeves are Elizabethan / frills of suds’), the

sage-jester persona, elegies to childhood. In one of the best poems,

‘Anthony Sant’, the title of an unpublished Graham

Greene novel, he

finds parallels between writers - ‘Two fat volumes for a life

outpiloting death / while I laze in the wake of what you

wrote’.

And later: Proof

he’s really a brother, a chum,

a bulwark in such dark hours, as publishers know when readers fail to erupt. Ah, far less risk besets the unpublished manuscript. In many poems, Sant is straitjacketed by a traditional sense of melody and rhythm, with corrugating internal rhymes and metronomic assonance. Although he pays homage to such unlikely forebears as Larkin and Graves, as well as Pope and Browning perhaps, he misreads Larkin as pure domesticity and Graves as wobbly excess, and so his imitations misfire. Developments in Sant’s work are chronological and philosophical, not linguistic. The long fourth section, ‘Summertime’, details a family holiday, and though the odd formal rhyme parcels up the action, this poem is too attached to the subject it puzzles over at length in a form of biographical penance. Sant echoes Ted Hughes at times in his ‘Green Man’ poems, with their epigraph from Graves and he also uses some Berryman-like inversions and contortions unconvincingly: There,

on the slippery deck, I first

met you,

famous poet, who could tilt the globe of memory, exile words in blue acres, exact, within sea-whipped cartography’s grid, a lasting measure. Compare that to Berryman’s ‘Dream Song 283’: I

seem to be Henry then at twenty-one

steaming the sea again in another British boat again, half mad with hope: with my loved Basque friend I stroll the topmost deck high in the windy night, in love with life which has produced this wreck. The last section has a series of poems extrapolating single objects - moths, ferries, pencils - and this barcode poetry is a common device used by many. At other times poems are choked by inflated verbiage - ‘This returns to me now, checked, / since old reading from memory bleaches’. For Sant poetry comes with specific purposes and equipment whereas for Curnow [The Bells of Saint Babel’s] poetry is all-inclusive. Curnow’s writing is refined, not to conform to tastefulness, but to convey his matter most clearly. Some writers’ careers are a hacking away at the marble until the figure appears, others’ constant hackings only roughly order the shape into any change, but each change is neither better nor worse than the previous attempt. The Impetus of Poetry - Russian Ink Paul Kane Australian Book Review, No. 231, June 2001 Wallace Stevens once remarked: ‘One of the essential conditions to the writing of poetry is impetus.’ It’s a statement worth keeping in mind when confronting a new book of poems because thinking about impetus helps us locate the concerns of the poet and the orientation of the book. Since poems are not objects so much as events, what drives a poem helps govern how it arrives at its destination - how, in fact, it is received by that welcoming stranger, the reader. Poems reveal their origins, whether they intend to or not. What Emerson says of character, that it ‘teaches above our wills’, that ‘we pass for what we are’, is true for poems as well. So it is not an idle question to ask of these books - these poets - their impetus, remembering that ‘impetus’ derives from the Latin ‘to seek’. I think it would be a mistake to assume that these poems seek to communicate with readers. The impetus here is not self-expression. At this point in their careers - and that’s a telling word in itself for a poet - both Andrew Taylor [Götterdämerung Café] and Andrew Sant have established themselves in durable fashion. Taylor, born in 1940, has just published his tenth volume of poems; Sant, born in 1950, his sixth. Neither, at this juncture, is likely to believe that he is reaching out to a populous audience of poetry lovers. Except in a few cases, that’s a supreme fiction, though a necessary one. Nor are these coterie poets, writing for a small devoted band of followers. No, like most poets at mid-career, the impetus is to write the poems that they, as poets, seek to write. If that sounds tautological, it needn’t be: devoted poets are devoted to their poems; they are ‘makers’, whatever their readers may, in turn, make of them. Consider the opening poems of each volume, and the way they gesture towards the writing of poetry. Sant begins ‘Nightfall’ with the lines: The

leaves release their light.

Bees, the fuchsia’s guzzlers, quit their day routine as somewhere a voice calls, ‘Come inside.’ That voice is presented as a domestic one (for the poet) and an instinctual one (for the bees), but it also serves as the voice of impetus, the call to turn inwards towards poetry, to ‘Come inside’. The whole poem in fact hinges upon the moment when ‘the past and future / fold in the breadth / of all the air’. We are left with enigmatic phrases that signal the presence of a poem seeking its poet:

Then try repeating:

‘Dark clouds over Siberia’ and ‘I write with Russian ink’. Similarly, Taylor writes in ‘Das Abendland’ (that Occidental realm of Western thought and desire): Still

there’s kindness

a refracted glory in this proximity to Eden if one can bear the burden of absolute kindness. The kindness of natural beauty here is burdensome because it is absolutely beyond recompense; we cannot adequately repay the gift of life. In the same way, a poem is a ‘refracted glory’, a kindness language bestows freely upon the poet no matter how hard the poet may be working to be equal to it. If there is an ethics here, it is to write the best one can. This is not to suggest that these poems are merely self-reflexive or self-regarding. On the contrary, both poets engage with the world and speak to those encounters we denote as experience. What, then, distinguishes them, in both acceptations of the word, ‘to separate’ and ‘to recommend’... Andrew Sant’s poetry, like Taylor’s, evinces a sharp intellect at work, though Sant’s poems come across as more restless perhaps, more driven to seek out new approaches, new retrievals. There is a seven-part poem that takes up the name ‘Anthony Sant’ (the title of Graham Greene’s first novel, which went unpublished). It’s a witty poem in which the character Anthony learns of a namesake, Andrew Sant, who is living in Tasmania. The second section of the book is devoted to ‘Green Man Poems’, in which the tree-spirit of Frazer’s The Golden Bough becomes a curiously contemporary figure. And the fourth section is a long narrative poem, ‘Summertime: A Holiday Chronicle’, which details the amusing exploits of two couples caught up in a mysterious financial speculation. All of these poems display Sant’s quick inventiveness, which extends to the characteristic movement of his verse: he is fond of short lines with rapid shifts of sense and sudden stops, where one encounters single-word sentences in the midst of a line. This accords with Sant’s keen eye, which invites us to see as he sees, where the concern is more for immediacy than meditation, for compression more than extension. To write narrative in such a line is a challenge, but Sant is capable of it. At times, I miss the sweep of those long verse lines so captivating in earlier work (Brushing the Dark, for instance), but there are memorable poems here to be sure. One is the sonnet sequence (in the difficult Petrarchan form), ‘Belli’s Shade’, which narrates a love affair in Rome between a visitor and a local beauty. Wryly, sonnet four begins: Above

him, exalted, that later week,

since on his back he gained a better view, a fresco of the Virgin, robed in blue, was one position, swapped about, until each peak released the lovers, breathless, cheek to cheek - Another fine poem is the moving memorial to Gwen Harwood, ‘Ferries’, where: There,

on the slippery deck, I first met you,

the famous poet, who could tilt the globe of memory, exile words in blue acres, exact, within sea-whipped cartography’s grid, a lasting measure. Here it is memory that makes for the memorable, and at times one can sense in Sant’s work a tension between invention and remembrance. In ‘Moths’, the poet is recalling a scene out of darkness,

...since memory

comes increasingly to seem a habitation. Whether Sant’s poems inhabit memory or seek an imaginative realm, they are impelled by a receptivity that requires an openness to their own processes. As he says in ‘Waiting Games’: Waiting,

too, needs a strategy

as artists do, heads askew, gazing like the commuters, here, in cold air. Both Sant and Taylor understand such waiting. In poetry, it is a strategy for action, an essential condition for a poem’s impetus. Outside & Beyond - Russian Ink Chris Wallace-Crabbe Island, No. 86, Winter 2001 In the case of Andrew Sant, we turn to an old Island hand; he edited the journal - with Michael Denholm - for a decade. I realise, too, that his first book of poems was published as far back as 1980. This being the case, it is surprising that he has not had more critical attention. Sant appears on stage quietly, but he has range: he sets himself projects. He exhibits some of the qualities which a nineteenth-century critic found in Browning: ‘the cunning prying into detail, the suppressed tenderness, the humanity - the salt intellectual humour’. As an example of the last trait, he offers a suite of seven lyrics on the fact that Graham Greene’s unpublished first novel was called Anthony Sant. He gets around, with a fine poem on ‘Waiting Games’, a nice closure on pencils (he has beaten me to the draw on this theme), and a tribute to that larrikinesque Roman sonneteer, G.G. Belli. What I have called his projects include the eight elegiac ‘Stories of my Father’, fifteen pages of Green Man poems, and also a fictive holiday chronicle, done in the free tercets which suit him as a medium: ‘That Viet Nam

War,’ a serious

son is saying, flywire door slamming behind him, ‘did it generate economic gloom in Asia?’ His father is an arse reversing out of the fridge. And, of course, Vietnam was the Cold War in reverse. But this is also an ordinary kitchen; it enters what Randall Jarrell called ‘the dailiness of life’, as we can find it doing so often in Sant’s inventive poems. These poems use long lines or short, sonnet, parody and prose poems; there is even a ballad with the malty refrain, ‘Halm, Guinness, Fosters, Bass’. The guy who inhabits Sant’s poetry is clever, but is also a genial humanist who proffers the mild request, ‘Give me extremes of cold and hot / mixed in a mega-ritual’. Just the thing for a dinner guest. Book Reviews- Russian Ink Michael Lang Togatus, February 2001 As a reader it is a joy when you read something so well crafted in its style and energy that the effect is electric, sincere, almost profound. This is one of those books. Andrew Sant’s most recent book of poetry is fairly dark, never dull and very often funny. As with any writer worth their salt Sant’s work allows the reader to indulge in a fair whack of self-examination. Writing about life, love, the sociological importance of showering, waiting, and the guises of mistrust, Russian Ink is a volume of work that will grasp the heart and hold your attention. The touching and revealingly human ‘Stories of My Father’ and the humorously dark and refreshingly accurate ‘Summertime A Holiday Chronicle’ contrast dramatically with Sant’s ‘Green Man Poems’, such as ‘The Sensualist’ and the more Ballard-like ‘Greenland’. Sant has the ability to give to his writing an honest craft that makes for a satisfying book of poetry. Hobart Launch John Collins (publisher) Moorilla Museum, Hobart, 1 February 2001 A book launch is a pause between drinks and the hopeful ring of the bookseller’s cash register. This is no lonely boat to be launched; there’s quite a Sant convoy afloat. Over 21 years, there have been six volumes of Sant poetry. Angus & Robertson (of memory) published three. Heinemann (‘that Trollop’ according to Andrew) one and Black Pepper, now two. And that is no mean effort when you consider the range of Sant activities; Founding editor of Island , compiler of anthologies, teaching, two daughters, much acquaintance with hostelries in Hobart and elsewhere and now an Arts mogul to boot! At this stage I should mention Kevin Pearson, publisher at Black Pepper. We spoke the other day and he assured me that is spite of all printing gremlins, the finished volume would be here today - and it is! A word or two of explanation. I have no bottle to break over the bows. I am only a very part time reviewer and certainly no poet. All I can do is enjoy the work and then attempt to trace a teasing track that may encourage others to follow. As a long ago publisher, one of the breed defined by Sant as ‘that suspect companion to authors’, I can appreciate the ‘dark hours when readers fail to erupt’. So let me in this pause between drinks, wander inside and outside the pages of the latest Sant collection. Its title can wait until later…. You may have come across the recently published Michael King biography of the New Zealand novelist and poet, Janet Frame. At one point, Janet says, ‘the last thing you want to be is literary. I write because I’m scared and haunted and lonely and in love and full of wonder. I am not thinking of what I shall say - in fact, I do not remember how I manage to say anything.’ Andrew Sant, in his introduction to a selection of his poems which appeared in John Kinsella’s Landbridge - Contemporary Australian Poetry, gave it a related but different emphasis: ‘a poem’s genesis is likely to be triggered by initial observation, less frequently by print. The way a poem proceeds, the connection it makes, relies as much on instinct as intellect.’ In this work observations of all manner of things abound from the micro to the macro in landscape, a myriad of places domestic and foreign, and personal situations, reflective and introspective. There are robins and honeyeaters, train journeys and railway platforms, seeds, sacks and skin, water, trees, bees and deserts, conferences, books and boats, bones and beer. 2 But there is little doubt that the intellect is very much a sustaining force and the result is that as in T.S. Eliot (I hope today’s poet won’t mind the reference) there is always more than one level of meaning - a subterranean river like the Saraswati in constant movement beneath the surface - in most if not all of the poems. An example is the poem, ‘Words for Malaysia’. The language is at once pointed and hard yet seemingly listless; the meaning or inference at once positive and negative. The result is a similarity to the apparent contradiction that, over three hundred years ago, George Herbert tussled with in his Bitter Sweet. Although it might be said that George was a little more concerned with the Lord and his doings than is Andrew! I

will complain, yet

praise,

I will bewail, approve, And all my sour sweet days I will lament and love. Throughout, there is much humour to be found; there’s sex in many of its convolutions, much of the colour green and in the midst of all, a poetic novella, 'Summertime'. There is also that filial uncertainty - the mark of Abraham rather than Cain - in the group of poems called 'Stories of My Father'. From the poem, 'Personal Pronouns', comes these lines: Fixed

in binary opposition

They proved he could Never grow old nor I grow up. I just wanted him off my back. Now, it’s the certain weight I lack. This came to me as a sudden reminder of many other poets who have felt similarly as they strained for an understanding of their fathers. Seamus Heaney. I

wanted to grow up and

plough

To close one eye, stiffen my arm. All I ever did was follow In his broad shadow around the farm. I was a nuisance, trying, falling, Yapping always, but today It is my father who keeps stumbling Behind me, and will not go away. Or Sylvia Plath. I

was ten when they

buried you.

At twenty, I tried to die And get back, back, back to you. I thought even the bones would do. Or Fay Zwicky as she set out to compose her Kaddish. 3. All that is but a snippet of what you’ll find inside the covers (brilliantly designed by the partner of a poet). Sant may have preferred ‘between the sheets’! It is over to you to buy, to read, at times to puzzle over but always to enjoy. Drinks are calling but before I go - a word or two about the title of this collection - Russian Ink. For someone whose almost last poem in the collection is a paen in honour of pencils, the title may seem strange. But is it? For those of you who are familiar with the last published Sant collection, Album of Domestic Exiles, you might remember these lines from ‘Blotter’: So

I wish you dreams

Of full ink bottles in desks And libidinous pens Of promiscuous Quink. We know that Russian leather is a particularly special variety, as is Russian Sheet Iron and Russian Matting - they all get a guernsey in the Macquarie and the Oxford. We also know that ink, the word, had its origin in Greek. It was that purple substance used by Roman Emperors for their signatures. An inkhorn is the ink vessel but an inkhorn term refers to a learned or bookish word - words particularly in vogue in earlier centuries when writers used Latin and Greek to underscore their erudition. We may know too that an ink cap is any mushroom of the genus Coprinus whose gills disintegrate into a blackish liquid as the spore matures. We know too that an inkster is a scribbler and that if you’re inked, you’re drunk or in some way intoxicated and that an inkling is derived from the Middle English inkle which once meant to mutter and now is more likely to mean a linen tape like the thread that binds... So, take your pick. Add to or subtract from the above being always careful to add a Russian - a touch of the very mysterious - and you will end up with something , like this collection, which is very distinctive and special. May the ink run black - ‘ever so black on it’ - and cause a volcano of readers to erupt with healthy profits to all. Melbourne Launch Brian Matthews Purple Turtle 162-168 Johnston St, Fitzroy, VIC February 2001 It’s a great pleasure for me to be asked by Andrew to do the launching honours tonight for him and for the redoubtable Black Pepper Press. Nothing in publishing these days is easy. I bet there’s scarcely a single person in this group here to celebrate Andrew Sant’s work, who has not attended at least one launch where the book in question didn’t actually turn up. It was on the wharf during a strike, or the printers had had a fire or somebody wanted to pulp it... or something. Black Pepper Press - because it is daring and innovative - often walks a knife-edge of one kind or another to pursue its excellent work in the cause of contemporary Australian poetry. On this particular occasion, the knife-edge turned on the book and lopped two lines - the last two lines - from one of the poems. One of those little subversions that are traceable to no human or other agency and that just have to be borne. Kevin Pearson moved quickly to send out the abandoned couple of lines so that they could be stuck in at the appropriate spot on page 107, which I trust you have all done. In my case, I received the two lines for sticking in, but not the book. In the true spirit of show business, however, I have prepared a long speech with which I shall launch the two lines. None of this is true of course, except for the encomium for Black Pepper Press. I do indeed have my copy of Russian Ink - a very handsome book and representing Andrew Sant, I would say, at pretty well the height and imaginative amplitude of his considerable poetic powers, of which more in a minute. Andrew and I go back a fair way: he is one of those friends you don’t remember actually meeting for the first time. He was just always pleasantly there. We’ve passed much time in bars and other salubrious venues talking about literature and life and resolving both to our temporary satisfaction. He’s always been admirably a literary man, living by his wits, his imagination and his words. And it was as a consequence of his exercising of his wits that we shared a sort of literary coup. Back in the early nineties, Andrew had what I thought was the very good idea of getting a number of writers to write about their other lives - what they’d done before taking the plunge into the notoriously dangerous literary world. The book, edited by Andrew, was called Toads: Australian Writers: Other Work, Other Lives - a title which not only took clever momentum from Philip Larkin’s poem ‘Toads’, about how the Toad work squats on our lives, but also boasted two colons. This was not as interesting etymologically as it would have been anatomically, but it was daring nevertheless. The book had a bright green cover in deference to its namesake, the toad, but, despite excellent contents, did not do well. It gained a delayed notoriety, however, when, four or five years later, Helen Demidenko, at that time the award-winning, controversial author of The Hand That Signed the Paper, published a short story in the magazine RePublica (since defunct) which lifted large chunks of my contribution to Toads, word for word and without a tremor of acknowledgement. Even allowing for her self-acknowledged difficulty in the past with an intermittent capacity for photographic recall of unattributed material, it was a fair cop and she was caught with a consignment of smuggled prose, street value - very little. Thus did Toads - Andrew’s very good idea - win at last its just due. No such ambivalence, of course, affects Andrew Sant’s reputation as a poet or in any way detracts from the important and impressive body of work which amounts now, with the addition of Russian Ink, to six fine collections of poetry. From the very start, Andrew’s poetic voice was distinctive and original. An early romanticism was even then toughened and undercut by a saturnine wit, a refusal to be easily won over by the excitements of the poetry game. In Russian Ink we have a poet, as I said at the start, who must be at or near the height of his powers. How else explain the marvellous assurance of

Spooled,

past use-by, his cache of film matched every holiday never taken from ‘Stories of my Father’, where the vernacular mixed with a deliberate sparring with dissonance, contribute to a moving, almost unlikely pathos. There is a kind of awkwardness here that becomes loving, a salute to the man. Or, how else explain the brilliance of imagery. Here is a man, irate, puzzled, hurt, doing the washing up: At his wrists

His sleeves are Elizabethan Frills of suds Till he finds the bowl They bought in Adelaide And quips, ‘Boys, The archaeology of the sink...’ Though before he’s shown it, It’s gone to pieces at his feet. Time after time in Russian Ink, a spareness of line that you would swear must cancel out emotional depth comes up with intense pathos, or beautifully hinted tragedy. Yet this same poet, who seeks ‘the square root of events’, who wants to ‘throw open the windows to ontology’ because there need to be some explanations, who, in short, will take on the complex and the mysterious in a poetry that is always up to the job, this same poet can come at all the mysteries and heart aches with parody and satire as readily as with intricacy: Between night and day [Reads from pgs 60-61]. Russian Ink is exciting, intellectual, vernacular, complex, funny and witty by masterly turns. I have honestly found it terrific stuff and I commend it to you. It’s an honour to have the opportunity to launch it on its way, which I now do with great pleasure, wishing book and author the acclaim and success they so thoroughly deserve. | |||||||||