Tassie

Mind for Murder

Christopher Bantick

The Sunday

Tasmanian,

2003

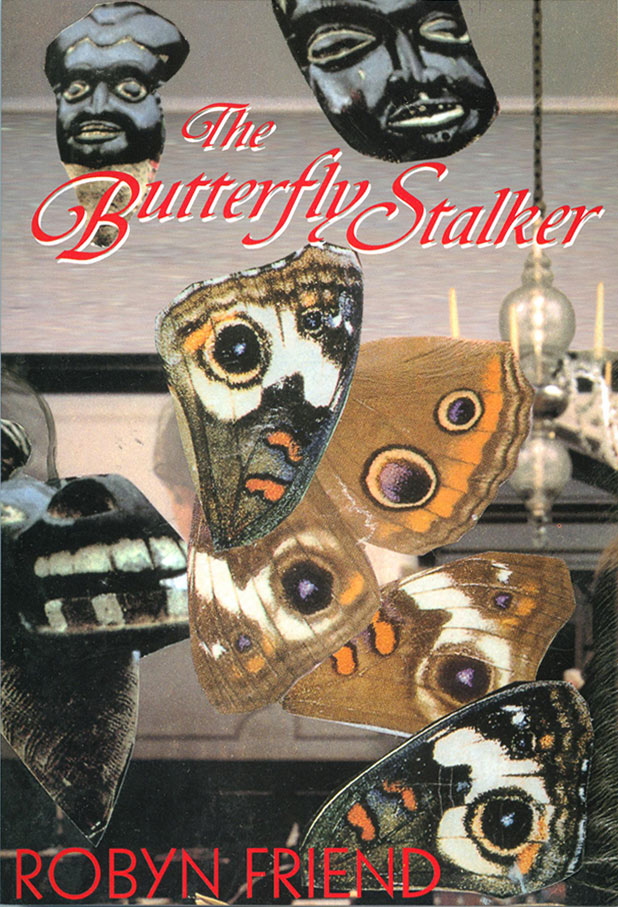

From the opening page of

The

Butterfly Stalker, we sense something ominous is about to

occur.

Robyn Friend’s novel is one of those rare books which is both

frighteningly plausible and compelling.

Although a well-plotted and determined crime is at the centre of

the

story, Friend cajoles us into thinking that perhaps it is a figment of

our imagination. This is a clever book.

Friend lives in Launceston. The novel is set in a place which is

not

with any certainty Launceston, but there are temptations to see it so.

It is, however, a very Tasmanian story.

In the opening chapter, we are told the protagonist, Theodora

Dante, is

writing a history of the unnamed city. ‘Not a particularly

adventurous

task,’ she says. ‘More a join-the-dots companion

for the sightseer.’

This might seem innocent enough, but beguiling readers is

Friend’s

strength. We soon realise that Dante is also intent upon killing

Daniel, a stained-glass artist who lives in a nearby deconsecrated

church.

The story is told.by Dante.

‘The first person enables me to get murky,’ Friend

says. ‘I can go

deep

into the psychology of a character.

‘It cuts out the distance between the reader and the writer.

It

gets

the material of the story and the reader together

immediately. No

one is relaying it through a third person.

‘I like playing around with what goes on in the human mind.

The

first

person enables the reader to experience thoughts more

directly.’

It doesn’t take us long to realise that Dante is a seriously

unbalanced

character. Her coolness in her self-acceptance that she will commit

murder is chilling.

So too is her voyeuristic absorption with the lives of those who

live

with her in what was once an inn but is now divided into three flats.

There is the ‘too starched’ nursing sister, Suza,

who’s having an

affair with a local clergyman.

She tells Dante, and us, that this is her mission; she is

‘rescuing him

from his church, from his religion.’

Then there is Angela and Hadley, living out an ‘intense

nightmare

of

married life.’

These are interesting diversions to the overall narrative thrust

of the

story. What dominates is the city and the church where Daniel lives.

Friend says that she left the city location unidentified for a

particular reason.

‘It is not Launceston but a geographically fictionalised

place. It

could be any city anywhere. Then again, if you take a whole lot of

impressions of where you live, they come out in other ways.’

We are told that the city is on an island. Dante is anything but

murky

when she declares: ‘Now, when you understand it is this

islandness

explains much of the psyche here...’ we feel there is

something about

the isolation which has prompted her to stalk Daniel.

Friend says the depths or Dante’s thinking fits with her

understanding

of Tasmania

‘For me, Tasmania is paradoxical, a place of startling light

and

dark

places. Here there are pastelled shades and a gothic feeling as well.

It’s never wholly one thing or the other.’

It would be misleading to read this story as a subtle warning that

it

is life on the island which is responsible for her behaviour. She is

simply mad.

Needless to say, Daniel and butterflies are connected. All the

more so

as he made the paperweight, a butterfly enclosed in glass, which Dante

intends as her murder weapon.

Back to top

Fiction

The

Butterfly

Stalker

Cameron Woodhead

The Age, 19

July 2003

Robyn Friend’s second novel is a second-rate psychological

thriller in

which the narrator, a local historian called Theadora Dante, plots to

kill a stained-glass artist who inhabits a nearby church. From her

third-storey apartment, she observes the romantic foibles and domestic

disputes of the women living beneath her, while unearthing the darkest

secrets of the island city she inhabits. The way that Friend

interweaves past and present is mildly absorbing but her prose is

purple and prone to affectation. And if

The Butterfly Stalker

is typical,

the editorial standards at Black Pepper leave much to be desired. The

book contains solecisms that would induce wild lamentation in the

reader if they weren't so unintentionally hilarious, How cool are

‘lava

floes’, for example? And how long do you have to wait if

something is

‘on queue’?

Back to top

The Butterfly

Stalker by

Robyn Friend

Sumanyu Satpathy

Newsletter IASA

(online),

Indian Association for the Study of Australia, February 2003

Set in a nameless city, which nonetheless shares a close resemblance

with Launceston in Tasmania,

The

Butterfly Stalker tells the story of Theadora Dante, its

narrator-protagonist. She has been commissioned by the City Council to

write the official history of the city in which she lives. While

researching her subject, Thea comes across archival material that

threatens to unmask the powers that be, exposing the horrible doings of

their ancestors, the island’s first settlers in the

mid-Victorian era.

Using these bits of information she begins to chart another history,

the sordid unpublishable story of the ancestors of the city’s

present

lawmakers. She lives in a top-floor flat of what was earlier an inn,

with a history of its own. In the flats below live a couple ensnared in

a marriage of dependency and violence: Angela and Hadley; and yet

another couple: an adulterous nursing sister Suza and her clergyman

lover Paul. Thea discovers that the rumour about the house being

haunted may well be true; and further that these characters may well be

living each other’s lives, and, maybe, die other

people’s deaths.

Thea’s experiences lead her to plot the murder of her lover

who is a

stained-glass artist, Daniel by name living in a dilapidated, Gothic

church overlooking her window. The suspense of whether she succeeds in

carrying out her plot or not carries on till the end. The other subplot

pertaining to the historical exposé is also held in suspense

till the

very end.

This bare outline of the novel, of course, fails to do justice to its

rich and intricate symbolism, its highly subversive politics, and what

is more, its technical brilliance. For, beneath its narrative surface

runs a seething undercurrent of anger and protest directed at power

structures in Friend’s city, Launceston (‘the

brooding pretty prison’

as she calls it in ‘This Pretty Prison’). After

all, because of her

political activism, she has been called names in the recent past:

‘a

communist’, ‘lesbian feminist’,

‘a ratbag’ and so on. Because of the

novel’s sharp indictment of the inhuman implementation of the

political

agenda of the city’s founding fathers, and of the erasures

performed in

official history writing, it may well prove to be as controversial as

her first novel

Eva

is. I,

therefore, shall proceed to bring in some more details.

First, that the central symbol of the novel is a triptych by Daniel

comprising three images of feminine sexuality. The artist has used Thea

as the model for the triptych. The second symbol that dominates the

narrative is the glass paperweight gifted by Daniel to Thea in which a

butterfly in flight is cleverly captured. She plans to smash the first

by using the second one as a weapon. The self-reflexive novel wonders

more than once how the narrative simply cannot do without the primacy

of the number three, already suffused with Christian symbolism. But,

here, the idea of the Trinity is treated with utmost irreverence.

The multi-layered narrative is the result of many a crisscrossing of

spatiotemporal frames. That the city is no geographical fiction becomes

evident from the close resemblance it bears with present-day

Launceston. Placed beside the other aspect of the novel, its tendency

to parody stereotypical ideas and icons, the interweaving of history

and fiction in the novel makes it highly intertextual.

This parallel between the discursive and the creative alerts us

immediately to the falsity of the binary in the context of

postmodernism. In the novel, the unofficial history, which is destroyed

by Thea at the end, attains a performative status as, by articulating

the so-called suppressed history, it actually lays bare the ugly past

of the city’s founding fathers.

What is noteworthy, however, is how Friend is able to interweave the

two histories, and the stories of the lives of the fictional

characters. Whatever happens to the fictional characters seems to have

been predetermined by the history of the place or the people they are

connected with. There is a trace of the naturalist tradition here. The

main plot around the life of Thea and Daniel (and her husband),

however, is used for raising aesthetic questions, about the power and

purpose of art. But, like the other man-woman relationships in the

novel, this relationship is also used to explore problems of female

subjectivity, and sexuality. The novelist interrogates the use of the

female body by male artists to serve patriarchy, and the eagerness of

the women as willing victims. At one level the triptych is quite

obviously a representation of the stereotype of woman as the lover,

mother and witch-temptress. But Thea deconstructs it for herself. The

same can be said about the paperweight. The butterfly stalker is

undoubtedly Daniel. But both, the image of the butterfly and Daniel

transcend their particularity to the universal image of the sexually

exploited and exploiter. Thea, Angela and Suza, for all their

differences replicate and relive each other’s lives even

while reliving

the lives of the mother who was killed by George Ratford. Eventually

Angela is murdered by her husband, Hadley, because she refused to

abort; Daniel does not want Thea to become the mother of his child, and

there is a hint that he used his psychic powers to destroy the foetus.

Thea nearly dies of a miscarriage and is saved a second time from a

suicide attempt. In her fight against the perpetrators of crimes in the

past and present, she decides to first expose the generational history

of crimes and their present-day descendents, and then take her little

personal revenge. Intriguingly, after delaying the revenge Hamlet-like,

she does not kill Daniel, and destroys the typescript of the second

history. Shrouding herself by a haze of metaphysics and aesthetic

theory she persuades herself into believing that Daniel, though living,

is yet dead. And she preserves the history of the gory past in her

mind. It is this ending which is the most dissatisfying for me because

it sounds so defeatist. Or, is it left deliberately disturbing? This is

debatable.

Friend’s ideological moorings may well have been shaped by

intellectual

and political developments within Australia. After all, (Germaine

Greer)

The Female Eunuch

and

The Empire Writes

Back (Bill

Ashcroft

et al)

were

influential works by Australian academics. But, in spite of what she

calls the ‘islandness’ of the fictionalized

Launceston (or Tasmania or

for that matter Australia) the effect of globalization, of political

activism among writers cannot be ruled out. Yet, the blurb of the novel

makes the innocuous claim that the yet-to-be-published book is a

psychological thriller. I do not know whether such a description enjoys

the approval of the author. But, having read the novel (novella) many

times over, and carefully, I feel that the description is misleading.

As I said the novel is self-reflexive at many points. What it does not

reflect on, however, is the novel’s preoccupation with three

kinds of

hegemonies: patriarchic, territorial, and racial. One

wouldn’t like to

schematize the novel so neatly, one might still say that the twin

political concerns of the novelist, feminism and post-colonialism are

enmeshed in the multi-layered story, presented in the formless form of

postmodernism. In the process, Friend redefines the parameters of both

feminism and post-colonialism. If post-colonialism generally concerns

itself with the colonizer-colonized binary in a seamless and

undifferentiated pattern, where the voices of the aboriginal people are

systematically muted, homogenizing categories such as Africa and

Australia, Friend goes to the heart of the problem, by trying to

reconstruct the history of the aboriginal people. In her attempt to

fictionalize history, offering a new historiography altogether,

layering history and fiction, and avoiding realistic linearity, and

using self-reflexivity and irreverent parody as a fictional strategy,

Friend firmly places herself in the post-Patrick White generation of

writers.

We are told Friend has lived and worked in Launceston (Tasmania) and

Africa. She has worked at old-age homes, and with the aboriginal people

of the Huan and Channel communities. In her forewords and writings,

such as

We Who are Not

Here -

Aboriginal People of the Huan and Channel Today, dealing

with

these subjects she has given evidence of her concern and sympathy for

these marginalized people, helping them to articulate their problems.

She figures in

A

Writer’s Tasmania

edited by established feminist writers and poets such as Carol

Patterson and Edith Speers, and has herself written on ‘Sex

and the

Australian Writer’. These preoccupations and interests of

hers colour

the novel. In this she is a part of the process which overtook

intellectual life of Australia in the 1980’s. As Bruce

Bennett has

pointed out, in the decades following the `80s ‘Australia...

became a

testing ground for intellectual movements, including feminism,

post-colonialism and postmodernism’.

When I first heard that the publication of the novel, has been delayed

due to certain `unforeseen circumstances’, I attributed the

delay

simply to the inscrutable ways of the publishing world. After reading

the novel, however, I feel that there is cause for worry. I shall be

happy to be told that my fears were unfounded, and the novel has seen

the light of day.

Back to top

The

Butterfly

Stalker

The

Butterfly

Stalker