|

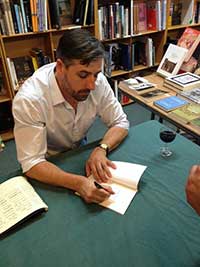

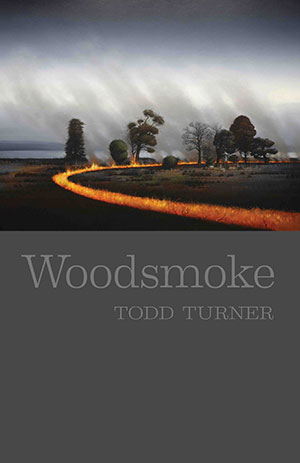

Woodsmoke : Todd Turner |

|

Woodsmoke has been shortlisted for the 2016 Mary Gilmore Award, 2016. The Mary Gilmore Award is given for the best first book of poetry published in the previous two calendar years (until 1999 for the best first book of poetry published in the previous calendar year).Reviews

Todd Turner’s debut collection deals mostly with the every-day: weeding, burning off garden waste, lying in the yard watching beetles, driving through the city, growing a bonsai wattle in a pot. The book is arranged in a loose chronology, with the earlier poems about rural childhood or family history, and the later ones set in adulthood in an urban environment – Sydney in at least some of them. The hinge between the two halves is Homecoming, a harrowing poem about the death of a brother. Many of the poems in Woodsmoke (e.g. “Shelling Peas”, which is excerpted on the back cover) consist of finely-crafted description set forth with little comment. The tone is sober, matter-of-fact, precise; and there is a fastidious avoidance of overstatement and verbal ostentation. They tend to regular stanzas, with lines of roughly equal length (there may be a more formal metrics at play): Whenever my mother took hold of the spade and handed me the cardboard box, I knew we’d be doing the weeds. She’d dig, while I stood there beside her as she threw them in. (“The Weeds” 5) A few poems (e.g. “Heading West to Koorawatha”, “September on Gasworks Bridge”, “Leaving My Place on the River”) offer the same basic aesthetic, but with irregular stanzas and line-lengths, and are reminiscent of poets such as Robert Bly and James Wright. The final section of “Heading West to Koorawatha” reads: It is almost dark, and the last of the light falls onto the canola fields, and onto the hillsides full of Paterson’s curse. I pull over and watch the sun sink into a stretch of grass. (“Heading West to Koorawatha” 2) Nature poets since Wordsworth have been afflicted by the urge to moralise, to view the natural world as a teacher of lessons which it is the poet’s job to interpret. Turner’s collection is, on the whole, markedly free of this tendency. In fact, I found poems such as “The Weeds”, “Lot” and “After Chores” a little puzzling: the descriptions are finely wrought, but the emotional significance of the activities described is unclear. Perhaps the determination not to over-state, not to over-write, can go too far. My favourite poems in the book (“Woodsmoke”, “A Penance”, “Nocturne”, “Fieldwork”) are those that break free of the propensity to (stylistic and/or emotional) sobriety. In the title poem, the language is unusually extravagant: woodsmoke sends up its flag of stored aeons and multifarious resins in a surly blue charred blaze. The poet reveals that he thinks of it

as what passes for benediction; the tenured door through which seasons pass, a time-tempered passage This poem ends: Somewhere lost among the welcome arms of the woodland trees I see it, adrift in a smock of ribbons, and set amid the downy blueprint of allegory, charted, in the aftermath of flame. (“Woodsmoke” 3) Todd Turner's Woodsmoke Carol Jenkins Australian Poetry Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2, December 2014 As

poems only exist as the experience of being read, the reader’s job is

to make the poem out of the gaps, to effect a surge of perception and

understanding, and it might be argued that it is in the space between

the words on the page, and the page and the reader, and the spoken word

and the listener, is the space that allows this to happen, where the

reader remakes this white space into her or his poem event. To my way

of thinking one measure of the poem’s excellence is the how reliably

this poetic effect can be found. I am a fickle reader, and I have read

some poems once and enjoyed them but on a return reading find they’ve

fallen quite flat: Single Use Only poems, as it were. A good poem is

tamper proof; it delivers on any number of rereadings, and amplifies

the friendship between poem and reader. So setting out to review a

book, is for me a naturally hazardous process: I have to want to

revisit the poems, and not turn what had been a pleasant one-off into a

penance. Todd Turner is a goldsmith, and the word ‘lapidary’ seems to hum about Woodsmoke, his first collection, an elegant production at a modest 56 pages. The opening poem, ‘Shelling Peas’, sets out the rhythmic practice of shelling. It’s ostensibly a simple telling of a daily task, but the coda to each stanza, ‘Snap off the ends, tear open the strip/, split the hull…’ builds and becomes incantatory by reiteration, reinforcing the poem’s declarations for routines and repetitions, and the narrator’s application to craft, his liking for needlepoint and lace-making. All of these careful acts of construction provide an understated trope for the making of poems, a podcast, as it were, to the pleasures of orderly practice. From this contemplative domestic space, Turner’s poems move out into paddocks, past Paterson’s curse along flat roads, in cars and trains. From the second poem, ‘Heading West to Koorathawa’, until the road brings us to an end in ‘Field Work’, we watch a cinematic landscape slide by. The landscape ranges from back of Bourke through the porous edges of suburbia, where farmland is subsumed into house lots, leaving poignant remnant blocks, into the inner city. One of the central concerns of Woodsmoke is the migration of country families to the city, what they bring and what they lose. The poems here often find the pastoral looking out from bridges and train windows, congested roads turn into cattle races in ‘The Road’: The Road A few miles in and the road forks into a funnel of diverging ways. I steer clear of the cars that veer and swerve, and stick to the middle lane. Soon the traffic chokes to a crawl and it feels as if we’re being herded along like cows on a cattle run, all bulk and weight converging in the crush. Further on, beyond the gridlock, I pick up the pace and regain whole minutes of lost time, drive on at speed across a region of winding suburbs with the hard ground rushing towards me, the dark tar glinting with sparks the way rivers do in sun. This doesn’t last long, and it’s back to the bustle and chug of bumper to bumper, of vast and middling distances, innumerable and immense. We halt—and then putter along. The clear lens of the windscreen holds true. The sheer dawn-dusk of it all pushing us to press on, to come full circle, like the conjoining head and tail of a serpent, who makes of itself a perpetual ring. Turner

catches the ironic rush and stall of traffic, wryly noting ‘now I...

regain whole minutes of lost time’, and when he conflates the

circularity of dusk/dawn with conjoined head and tail of the serpent,

we have not just the ambiguity of going nowhere fast in a

cattle/traffic race but a clever allusion, a whiff of that high sweet

note in petrol, from the benzene in the motif of the ouroboros famed

for providing Kekulé’s dreamt insight into the structure of benzene. A quick head count of noun groups to give a frequency distribution provides an insight into how Turner balances his palette. The noun subjects of Woodsmoke are broadly, in descending order of frequency: plants, animals, fields/terrain, rivers, roads, country towns, fire and smoke. He uses these to build a sense of down to earthiness that ranges from the subterranean up to the wink of starlight. In between the urban pastoral works are poems of quotidian practices and objects. Turner has a way of diversifying and then conflating his metaphors, so they amplify and illuminate each other. In ‘The Wireless’, he leads off with the evocative, ‘sepia tones’ deftly pairing the aural experience with visual nostalgia borrowed from photography and follows on with the hallowing effect of a ‘muffled sermon of kettle and cup’: The Wireless murmured in sepia tones; first creak of the morning, routine cockcrow, muffled sermon of kettle and cup. Little lamp light, dear hub of the house dawn kindler of draughts and cracked leaves, sweet shepherd of hob-fired broth, spirit level of whim and woe. Your console hummed from the rungs of the kitchen where no stool or step could reach your touch-tuned hearth. Upon the table, a stove warmed stout jug bubbled and brewed, knee-worn chair legs slid in under shadowed nooks. We sat and listened, hunched in the quiet. Potato eaters in the communal dark. Opening

the second stanza with ‘Little lamp light, dear hub’ brings to my mind

an echo of ‘Dear Soul Mate, little guest…’ from David Malouf’s

wonderful ‘Seven Last Words of the Emperor Hadrian’. More importantly

for Turner’s poem, this line sets up a tighter arrangement of the

alliterative runs that were introduced in the first stanza; we have

‘hub of the house’, then ‘dawn kindler of draughts’, a phrase with one

internal alliterative pair and a half of another pair in the next

phrase, creating a movement that works to lead the reader onwards. So

too do the nicely slant rhymes and half rhymes, hub/hob, hummed/rung,

reach/heart, proceed with their job of discretely carrying us on

without the obvious smack of settling into a predictable pattern. ‘The

Wireless’ builds its picture of a family with an adroit

‘family-lessness’: the family here is unnamed and unseen until the last

two lines and then only by actions, they listen ‘hunched in the quiet’,

an act of fine ambiguity that plays on the radio creating its own

silence, in parallel to the way a poem creates its own white spaces. Turner’s hybrid world of country/city has certain nearly painterly effects. While we are focused on a scene, it is frequently the light or the air that takes centre place, and provides an embodiment of the duality of place, evoked by phrases like ‘ ambling air that roams’ from ‘Mid Winter’ and then in River Birds ‘Strobing with its under-light/ to any passing thing.’ In ‘Pine Grove’, opposite the elegiac poem on a brother’s death, we spy in on a cemetery where mourners crouch and where the ‘unliving … have no words, no thoughts to speak of’, an interesting commentary on thoughts and words, and the numbness of grief. There is an uncanny uncertainty about Turner’s graveyard, and a certain knowingness about the odd juxtaposition contained in ‘Beyond the rows/of the flame-shaped cypress trees/ a man kneels above his own.’ Is it his grave, a grave of one his own or his cypress tree? The logic here is both nicely weird and entirely plausible. ‘Interiors’, a composed still life, opens as neatly as a venetian blind, with the drone of traffic and the nuanced pre-figuring of the river by the bridge and the final stanza ‘He draws the blinds/sees an ibis on the river/ pause… then take up flight’, where the neat enjambment of ‘pause’ works to give a sense that we are being given polite reading instructions, and then asked to think about it all. As a collection, Woodsmoke mines this kind of duality with deft technique. Turner often writes along an edge or brink to give the reader sense of depth. These are poems that don’t set out to obfuscate; here, lucidity, the pastoral and warmth of feeling prevail, and fine attention to craft pays off handsomely. I’ve focused here on the machinations of just four poems in this collection, but I think many of them will repay this kind of close reading. Todd Turner: Woodsmoke Martin Duwell Australian Poetry Review, 1 May 2014 Todd Turner’s first book is a very handsome object and an excellent collection of varied but essentially lyric poems. And, like all good lyrics, these poems are sensitive but tough and intelligent at the same time. Woodsmoke’s title poem is not only one of the best poems in the book but it is also important in helping readers make some sense of the other poems. The smoke of the title (significantly “woodsmoke” is compressed into a single, iconic word) is a kind of inversion of rain, another element which figures largely in the poems and is often associated with smoke. But the smoke is described in such a way that it isn’t simply the result of a natural process – the coal, timber or wet grass which is burning has its own history so that the smoke is that history making itself manifest: It

plumes from the fire’s red hearth,

sends up its flag of stored aeons and multifarious resins in a surly blue charred haze. Rain-cloud dark and featherweight, it leaks from any pooled heat or gone-to-ground tinder along the craquelure of lost leaves, rising tightly at first in a single plait before shaking out its winter hair . . . Not only is it the inverse of rain and an expression of the history of one of the earth’s forms of life, it is also described as “what // passes for benediction” and the end of the poem describes it as being “set / amid the downy blueprint of allegory”. History, grace and meaning are abstractions which bulk very large in Woodsmoke. This title poem is so central and so strong that, initially, you wonder why it is the third poem in the book rather than the first. The answer may be that that would make the rest of the book seem no more than a programmatic extension of a single poem. But I’m inclined to see other possibilities in the arrangement of the first three poems. The first, “Shelling Peas”, is one of a group of poems which deal with family life in the poet’s past, with history in other words, the history of his family. It is an odd piece with a refrain – “Snap off the ends, tear open a strip, / split the hull and with a run of the thumb / rake the peas into the pot. Repeat.” – which stresses the repetitive nature of the activity. Its own “blueprint of allegory” might be no more than the conventional trope of the artist finding the valuable fruit inside the dry shell but I think the emphasis is rather on the poet’s use of his hands “intent / and nimble as a lace maker’s”. Turner is, in professional life, a maker of jewellery (I’m not sure of the correct noun for this art) and may want to stress at the outset that his engagement with the natural world is not always of the passive, meditative type of the title poem. “Shelling Peas” has a counterpart, late in the book, called “Apprentice”, about the jeweller’s trade and which focusses very much on the doings of the hands. “Apprentice” might – in its “blueprint of allegory” – be about making poems:

The last link in the chain,

he combed through lost lemel for a glint. Given tools, his hands were engaged with implements of improbable need; wedlocked in the grips of some dogged perfection, jigged epiphanies, theorems in the crux of being stubbornly made . . . but I think the emphasis is on a profoundly manual engagement with the world. Between “Shelling Peas” and “Woodsmoke” is “Heading West to Koorawatha” a formally organised lyric in two five line stanzas of diminishing line length which focusses on the visual (“the last of the light / falls onto the canola fields, and onto the hillsides / full of Paterson’s curse”) and introduces the speaker simply as observer at the end. My sense of the idea behind this opening is that the three poems canvas different ways of approaching the natural world and, by juxtaposition, critique each other. The second and third are compromised by the first because they don’t detail the writer’s physical interactions with the world. The third is compromised by the first and second because they make it seem wordily interpretive and densely packed with meditative meaning whereas the third compromises the first two by showing how, in their suggestiveness, they can be coyly gestural. And so on. None of this may have been intended but those three poems together, rather than “Woodsmoke” on its own, prepare us for most of what happens in this book. Family history is the subject of many of the poems in the first half of the book and Turner is one of a number of recent poets to focus on (in Gary Catalano’s phrase) remembering the rural life. It’s not an easy thing to do well but there is a nice balance here between remembered sensations from a time of sensitivity and an appreciation of the way family members are both separate individuals and also parts of a genetic chain that includes the author. Thus a poem which begins with the father quickly modulates to an uncle’s memory of the grandfather – “could ride a wild horse to a standstill, // round penned horses all his life” – and imagines the grandfather looking sceptically at his sons before the poet, the most recent “link in the chain” (to continue the jewellery motif of “Apprentice”) looks at the fresh crops emerging year after year. There’s also a sensitivity here to responsibilities to previous generations and, perhaps, the thought that a man who has dedicated his life to poetry and making jewellery might appear an oddity, and even a disappointment, to the ancestors who produced him. It’s not an uncommon experience for Australian poets with a rural background since Australia is not, after all, one of those cultures where a family’s proudest achievement would be to produce a poet. We meet the proto-poet in a number of these poems, perhaps most interestingly in “Lot” which seems, at first, to be a poem about growing plants at a domestic level (the title refers to both a rural address and a rural fate) but quickly turns into a poem about burning the refuse and thus generating woodsmoke: I

can remember my mother jamming the rose

thorns and summer-end weeds in the fire with the back end of a hoe, my brothers and I spying into the flames, watching the cinders spray up over the fence, while the uprooted green stems crackled in the heat. . . . When there was nothing to do, I’d kick off a charred end of a branch from the fire bin and draw circles or birds on the pavement. Other times, I’d scratch my name in the dirt with a stick. It makes the point, fairly subtly, that the first expressions of childish creativity, probably common to all, are here made with a fire-burned stick which, as the title poem pointed out, had released its history to the air. As an isolated subject, benediction figures mainly in poems later in the book but one of these early poems is significantly called “A Penance”. It’s not an easy poem to speak confidently about as a reader but the early description of the situation – “I gathered pips from its / edges, back-burned and heaped smoke with / sodden leaves. I was given pods to split, straw / to pull and a grove of sticks to whittle a field” – is so impregnated with images that are significant in this book that one is forced to return to it and look at it carefully. It is about the processes of cutting out the dead wood and remains of the crop and burning it on granite outcrops (a word that one suddenly realises connects rocks with plants). But instead of allegorising this out into a statement about war – as Murray’s “A New England Farm, August 1914” does – it focusses on the ethical implications of tilling the land, calling it, somewhat mysteriously, “a reckoning”, and finishing up by making an offering:

Late harvest, when the wheat

bloomed, I made a wreath of roots and intricate weeds, hung it with a nail on a deadwood tree. I knelt beneath it shredding strips of sackcloth and rough threaded jute that had stored the seed of the harvest grain. The wind blew hard across the furrows, and ash from the outcrops plumed in the air. I stayed kneeling, and struck a match. It’s a complex holocaust containing none of the scent of animal fats to appease hungry sky-gods but instead the remains of what needs to be destroyed so that new life can prosper. There are complicated responsibilities being negotiated here and perhaps it is significant that the last of the poems about family is devoted to an Aunt Leila whose house was incinerated in the Black Saturday bushfires. At other places, benediction is approached more gesturally. “Nocturne” is a celebration of domestic bliss where, after putting his daughter to sleep, the poet makes her next day’s lunch and sees how the “servant moonlight falls faithfully / now, into the earthen pots”, and “A Gift” celebrates an ineffable moment of “stinging grace” when “everything that seemed distant / or unnoticed was drawn near”. “Grace” celebrates such moments but, instead of being open-ended, concludes by putting them in an ethical context: There

was something in the rain, in the way it fell.

Something in the way of the birds. And in the way of the river. Something in the way it fell. Something about how the river rose, and about the stillness of the birds on the banks in the rain and about the way the air made it feel possible to forgive - and be forgiven. Perhaps the poem that most intensely addresses these issues of history, the interrelation of life and death, and how we are engaged with both in an ethical sense, is the final poem of Woodsmoke, “Fieldwork”. There must be a glance at Seamus Heaney here though the title, like “woodsmoke”, is made into a single word whereas in Heaney the terms are separated, maximising the allegorical possibilities. The situation involves finding a dead magpie and burying it so that the natural processes of decay, reduction and at least some form of new life can occur: I

left her there to the hide beetles

and the flesh-boring burying beetles, who would come to grapple through seed-cone, stick and leaf, mud, and at last, by way of orifice, would sheath her, nosh on her ripe tissue and fleshy muck, before leaving eggs in a crypt scraped under her remains. Larvae would move into beetledom, into the birthwing of the hutted carcass . . . When he revisits the remains of the grave and finds a skull and a clump of feathers and wing we are provided with questions and an open-ended conclusion:

I know what the cycle

serves, but what is being served by the cycle? It’s arguable, I know – best to just walk and fall in love with the field, the beloved range of the ubiquitous grass. It takes some work at first to prise two meanings out of what seems a simple repetition of meaning in both active and passive voices – what the cycle serves should be the same as what is being served by the cycle. One way is to split the meaning of the word “serve” so that the active means, “I know what the cycle does – it serves Life” and the passive means, “Why is the cycle as brutally cruel and wasteful as this? Why must life be built on death?” Ubiquitous grass may be one kind of benediction (and a painless provider, when burnt in the family incinerator, of woodsmoke) but this is a poetry that wants to pursue questions about how we are engaged in the natural world as much as it wants to celebrate the blessings that world provides. As “Shelling Peas” suggests, it will be a “hands-on” approach. Australian Poetry Anthony Lynch The Weekend Australian, July 2014 Todd Turner is a younger poet, and Woodsmoke is his debut collection. Although Turner was born and reared in Sydney’s west, it is the pastoral realm that occupies him and makes him an heir to the more mature poets reviewed here, [Geoff] Page in particular. The poet’s parents lived in farming communities before moving to Sydney in 1959, and this slender collection draws heavily, and with great affection, on family and rural experience. The strong opening poem ‘Shelling Peas’ sets the tone, the rhythm of pea shelling captured in the refrain to each stanza, the poem a testament to the dignity of simple tasks. The title poem denotes woodsmoke as the signature of time and ‘what passes for benediction’, a ‘plait’ wending through land and the collection. ‘Mellowed Fruit’ is a prayerful poem to the farmworker. Other poems fondly record the poet’s father working the land, and ‘Homecoming’ is a touching account of a brother’s death. Drawing strongly from English pastoral traditions — right down to the preference for ‘fields’ over ‘paddocks’ — these poems are a country mile from the recent Black Rider anthology Outcrop: Radical Australian Poetry of Land. The disrupted landscape of that anthology will grant some readers little foothold, but amid Turner’s rustic calm one might long for a mobile phone to ring and snap the verse into a post-pastoral 21st century. In Nocturne, the poet stands in ‘the neon blaze of the electric / light of the refrigerator door’ while his daughter sleeps. It’s a superb image, and an instructive one. Sometimes, you need to douse the fire and go electric. Woodsmoke Geoff Page Australian Book Review - Sept 2014 Todd Turner’s first collection, Woodsmoke, evolves intriguingly. It starts in the ‘anti-pastoral’ mode founded by Philip Hodgins. Here the poet, long since relocated to the city, looks back with tellingly evocative detail but a divided sensibility on the life he (it’s normally a ‘he’) has now abandoned. Turner’s early poem, ‘Heading West to Koorawatha’, is a good example. It finishes: ‘It is almost dark, and the last of the light / falls onto the canola fields, and onto the hillsides / full of Paterson’s Curse. // I pull over and watch the sun sink / into a stretch of grass.’ Paterson’s Curse neatly embodies the poet’s ambivalence: it is visually beautiful but poisonous to livestock. Significantly, Turner’s action in pulling over to look at it foreshadows the metaphysical dimension that develops towards the end of the collection. The key continuity in this shift is Turner’s steady concern with verbal perfection. This at times can slow a poem’s impetus, and it is not for nothing that Turner, in a later poem, ‘Apprentice’, celebrates the would-be craftsman’s hands as being ‘wedlocked in the grip of some dogged / perfection, jigged epiphanies, theorems // in the crux of being stubbornly made’. In many of Woodsmoke’s later poems Turner is noting and/or recreating moments of what even secular readers will be happy to call ‘grace’. His short poem of that title reveals what interests him most, and the closing lines seem to reach out to embrace the book as a whole: ‘Something about how the river rose, and / about the stillness of the birds on the banks / in the rain / and about the way the air made it possible / to forgive – / and be forgiven.’ Review Short: Todd Turner’s Woodsmoke Autumn Royal Cordite - May 2014 http://cordite.org.au/reviews/royal-turner/ The poetry in Todd Turner’s debut collection Woodsmoke explores topographies of land and memory. Comparable to the approach of Australian poets such as Philip Hodgins and Brendan Ryan, many of Turner’s poems explore human interactions with rural landscapes. Turner’s biographical note indicates that his ‘parents were from farming families in the town of Koorawatha, situated on the Western Plains of New South Wales’ (v). Like Hodgins and Ryan, Turner is unafraid to include autobiographical references within many of his poems. The collection opens with ‘Shelling Peas’, a poem that may be read metapoetically for the way it details the poetic qualities of the quotidian. The speaking ‘I’ in the poem, presumably Turner, refers to a childhood memory of shelling peas, a monotonous task the poet ‘hardly tired of…just eased into a certain / order, felt a kind of rhythm at hand’ (1). This ‘rhythm at hand’ puns on the crafting of poetry and also emphasises the cadences of domestic labour, the obligatory cycles that can inform our imagination. It may be argued that for Turner, the consideration of memories through poetic encounters allows for an enhanced understanding of the self. Following this assertion, the poem ‘Shelling Peas’ may then be read as a Turner’s retrospective identification of a moment where he first began to perceive the poetic qualities of the diurnal, evident in many of Woodsmoke’s poems: Front porch, set up in a row of chairs, given a bucket of pods, we were told to wash the grit then prise the husk for peas. A chore I didn’t mind, I took my time over every pail, over each repetitive task… Snap off the ends, tear open the strip, split the hull and with a run of the thumb rake the peas into the pot. Repeat. (‘Shelling Peas’, 1). The three italicised lines ending this stanza become the poem’s refrain. It is within this refrain that one may understand the metaphorical process of the ‘run of the thumb’ as a means of extracting a moment or idea from its ‘hull’ and containing it – like the ‘peas into the pot’– within a poem. Through this process, Turner learns ‘to feel the variance between / each seam, between the notched ends, / the ridged sides’ (1). Turner’s use of the ellipsis also instills a subtle playfulness in this poem. Appearing immediately before the poem’s refrain, these ellipses simultaneously represent the ripe peas being extracted from their pods and the swelling thoughts occurring during such a repetitious task. Recollections of the past, both actual and invented, form the basis for many poems in Woodsmoke. Poems such as ‘Crop’, ‘Kooravale, 1959’, and ‘Kooravale, 1971’ are imaginings of farming and family challenges during the years before Turner’s birth. ‘Kooravale, 1959’ is particularly striking for the way it explores gendered obligations that may pertain to (but are not isolated to) farming families. The poem, dedicated to Turner’s mother, opens with an ominous description of a farmer ‘hacking the edge / of the boundary line with his scythe’ (6). Connections between masculinity and violence are made between this act of labour and the paradoxical complicity and victimisation felt in viewing such acts: From the porch my mother looks on, hearing the whip-sound of the blade, the light lowering down upon the crop with every cut. (6). The shortened line: ‘with every cut’ enacts the process it describes and also echoes the limitation felt by the woman in the poem; the reader may conclude that there is nothing left for her on this farm, this land is not her land. References to boundary lines, edges, blades, and traps also emphasise the restrictions felt by this woman, who is thankfully given a means of escape in the poem’s final couplet by following ‘the train line that is headed / the other way’ (6). The final line of the poem, ‘the other way’, is also shortened, suggesting that the act of leaving the farm is not necessarily an easier path to follow, it is merely a new direction. Turner’s poems, many of them written in unrhymed couplets, tercets and quatrains, are filled with acute observations of the poet’s immediate surroundings. Poems such as ‘Nightwalk’ and ‘Fieldwork’ explore the contrast between the natural and urban ecosystems, as the opening lines from ‘Nightwalk’ demonstrate: ‘Wedged between the suburbs and the city, / the parklands are a labyrinth in the dark’ (34). During ‘Fieldwork’, the collection’s final poem, the poet asks: ‘I know what the cycle / serves, but what is being served by / the cycle?’ the question remains unanswered, but the poem, and perhaps too the collection as a whole, become Turner’s attempt to grasp at such an answer. Like the smoke that ‘plumes from the fire’s red hearth’ (3) in the collection’s eponymous poem, ‘Woodsmoke’, some memories are as distinctive as smoke curling into the air, rich with possibility or menace. Turner’s poetry captures his observations of environment and his contemplations of memory in ways that allow for new meanings to rise up for the reader. |