Meditations

of

a Flawed

Groom

Meditations

of

a Flawed

GroomVivian Hopkirk deserves to be celebrated, not ignored Rodney Hall, The Sydney Morning Herald Hopkirk is an important writer Lisa Catherine Ehrich, Social Alternatives jumps upon the reader’s senses with the first word and never takes breath Robert Umphelby, Muse |

Book Description

Art

begins with puberty, with seduction. Ask the lyrebird.

Meditations of a Flawed Groom is an unashamedly philosophical novel, its language a cool display of a fabulous pyrotechnic. It is set in a Sydney jail. The narrator Stephen West, arrested for disorderly behaviour, is obliged to stay to discharge accumulated fines. From this point on the forceful and satirical action often takes place within the landscape of Stephen West's mind.

The bride implied by the groom of the title is unrestrained imagination. The hero is the prototype of the Romantic and Modernist artist. The author is a nephew of the painter Brett Whiteley, who decisively intervenes as a character in the novel.

Meditations of a Flawed Groom is an unashamedly philosophical novel, its language a cool display of a fabulous pyrotechnic. It is set in a Sydney jail. The narrator Stephen West, arrested for disorderly behaviour, is obliged to stay to discharge accumulated fines. From this point on the forceful and satirical action often takes place within the landscape of Stephen West's mind.

The bride implied by the groom of the title is unrestrained imagination. The hero is the prototype of the Romantic and Modernist artist. The author is a nephew of the painter Brett Whiteley, who decisively intervenes as a character in the novel.

Mr Vivian Hopkirk is a poet and prose writer of outstanding talent and dedication.

Rodney Hall

a powerful but anarchic talent

a powerful but anarchic talent

Geoff

Page, Books &

Writing, Radio National

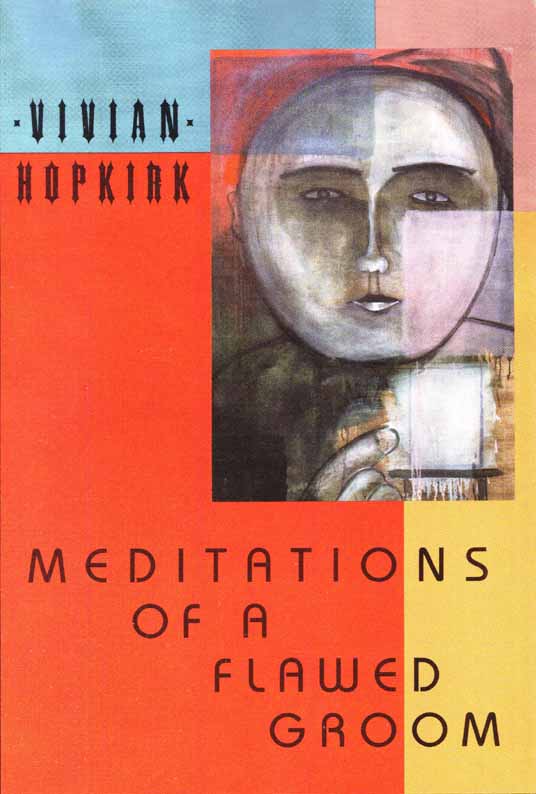

Cover painting Portrait of Stephen

West by John Baird

ISBN 1876044039

Published 1995

149 pgs

$19.95

Meditations of a Flawed Groom book sample

Back to top

part one:

the descent

10 sections

part two:

manoeuvring among the embryo angels

5 sections

part three:

the blue guitar

5 sections

part four:

the wandering protagonist

4 sections

Back to top

Comments by Alex Skovron

October 2009

I enjoyed Meditations of a Flawed Groom immensely.

I found it rich, colourful, dense, intense – a novel of ideas, an exploration of consciousness, with some splendid poetic imagery and exhilarating prose. At the same time it is an act of storytelling, and a relay of stories within stories – as in (for instance) the accounts of John’s adventures, or the Socratic dialogue with the dero. I liked your unabashed use of richly-charged, sometimes unusual vocabulary – though I felt that at times, like your hero, you are ‘in the habit of super-enciphering your sentences’....

In sum, I was impressed by your talent, and wish you success.

Back to top

Books and Writing

Geoff Page

Radio National, Broadcast February 1997

Clearly autobiographical in many, but not all, ways, Meditations of a Flawed Groom is a daunting book to review. As with most autobiographies one feels that in some sense one is reviewing the author rather than the work. In the book’s blurb we learn that Vivian Hopkirk is a nephew of the painter Brett Whiteley and it is not a total surprise to see that the late painter is hagiographically offered as a character in the novel. We also learn that Hopkirk is a poet and it is no surprise to see that the book’s narrator, Stephen West, is also a poet. The publishers also inform us that the book’s basic situation, a short stay in jail,has also been an experience of the writer. Given this extra-literary information we may proceed to the novel itself.

The narrator, Stephen West, in the course of a three day stay in jail, converses with, or listens to, a succession of cellmates: a young Aboriginal man called Morris, a philosophical derelict who is heavily into metaphysics and a painter who is an extraordinary raconteur. Occasionally he hears disconcerting activities in the corridor outside and is from time to time abruptly visited by the warders. In between there are various flashbacks, as for instance, to the narrator/author’s childhood and his parents’ marriage break-up, in which Brett Whiteley himself seems to have played a benignly facilitating role.

The style of the book ranges wildly from large slabs of indigestible philosophical dialogue (such as were almost never spoken, even by Socrates and his students) to humorous and highly engaging tall tales from the painter’s travels in Europe. Significantly the later are not from the mouth of Stephen West who seems to have had a terminal overdose of polysyllables and will never use two simple words when one arcane one will do. West himself explains this preference, though not necessarily convincingly. ‘As a rule’, he says, ‘one must be careful not to speak too mysteriously in the English tongue, particularly in the Antipodes, for fear of a smack in the mouth.’ One excerpt from the ‘dero’ sequence illustrates what he means. ‘In other words,’ says Stephen West, ‘God and the Cosmos are synonomous. God evolves. This life ensures that we begin at the darkest beginning and find our way in the gradual realization that we are responsible, not only to our selves, but the fortunes of all existence: to God.’

‘Hmrnmm,’ said the dero. ‘You certainly are a crack metaphysician. I admit that I like your style. Of course, you know what Albert Camus would say.’ Hopkirk, via Stephen West, may indeed by a ‘crack metaphysician’ but whether he’s a true novelist is less certain.

The problem with most of this book is that it really asks too much of its reader, especially in the opening sections. The narrator often seems pompously grandiloquent and the texture of both narration and dialogue is more or less impenetrable. One needs a kind of protestant self-discipline to persist and I was encouraged only by skipping ahead and noting that some of the later sections were rather clearer and so forced myself to go back and work my way slowly forwards again into those more open pastures.

Among the more congenial of such expanses is Hopkirk’s account of his childhood in New Zealand and the breakup of his parents’ marriage. The narrator says of his mother at this point that ‘she was proud and yet somehow abandoned by the extraordinary fame of her brother, who was, until he perished alone in a motel on the South Coast of New South Wales, one of the most remarkable men ever to pace the earth.’ Although this was not the universal view of the critics who reviewed Whiteley’s 1995 retrospective it is clear evidence of the artist’s heroic status in his nephew’s eyes, a view further confirmed by the commanding assistance given by Whiteley to his sister in giving her husband the bad news. ‘Brett was straight from the hip: ‘Man, we’re here to break your heart, and you have to accept it. It’s your fate, you’ll have to be real big. Fran is leaving you for this man, they are in love, and they are going to live in London. That’s the story, that’s the way it is and I have come a long way to tell you this.’

Another of these more open pastures are the tales told by his third cellmate, John, a painter, who is in overnight on a charge of ‘asleep and disorderly’ following a drunken night out with a woman that went badly wrong somewhere. The painter leaves Stephen West (and the reader) highly entertained (and mercifully speechless) with several tales of wild times in Europe with other Rimbaud-style artists and their women. The scene shifts considerably - France, Greece, Italy and Ireland - but perhaps most memorably to a plane trip in New Guinea with a drugged wild boar who wakes up in mid flight.

The novel ends with Stephen’s ejection from jail on the third day and his return to the inner city boarding house described earlier in the novel and tenanted by people of various sexual inclinations and no less strange than West himself. What the average reader will have made of Hopkirk’s novel by this stage is hard to say. Some, like the narrator, may be groggily relieved at their new freedom. Some will consider, with some justice, that they have wasted their time. Still others will feel they have been in the claustrophic presence of a powerful but anarchic talent which has not yet quite found its true metier. In any event, Vivian Hopkirk and his Meditations of a Flawed Groom will not slip blandly from their memory.

Back to top

shorts

Sydney Smith

Australian Book Review, No. 188, February/March 1997

These are the ruminations of one Stephen West during a three-day stint in prison. Groping through the murk produced by the author’s over-use of the thesaurus and under-use of the dictionary, I encounter Stephen’s co-inmate, an Aborigine from Redfern,who recounts his history of drug abuse and crime, which sets Stephen off on a line of reflection.

A people for whom we have inherited the responsibility of those who assumed to change the world, into which we have invaginated ourselves...

A page of this exhausted me. And it went on: ‘What a centrifuge of terrors and absence of communication or belief in the ductile holiness of a child.’ Good grief.

Look - this is a bad book. The English is usually deranged; the philosophical bits are trite or poorly reasoned; poetry and humour don’t exist in it. The recurrence of certain words: ‘vanity’ and ‘invaginated’ are two examples, gave me a picture of Stephen and his creator which I’m sure the latter did not intend. So that, when Stephen announced, ‘Estrange the child, and you estrange it from itself,’ I knew with certainty he had no idea the truth he spoke.

Back to top

Best books of ’96

Rodney Hall, novelist

The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 November 1996

My year’s reading has been dominated by Roger Milliss’s magnificent history of the Australia Day massacre of 1838, Waterloo Creek. Pauline Hanson ought not to be allowed back into Parliament until she has read all 750 pages. Milliss’s great achievement is to marshal a wealth of facts into a story of breathtaking drive and moral urgency. A thoughtful Christmas present for John Howard, too.

I have just begun The Glade within the Grove by David Foster. It is already proving to be Foster’s characteristic mix of comedy and erudition - massive, quirky and very good. I am yet again astounded that he is not more celebrated. Too much adulation is squandered on lightweight novels masquerading as literary works.

While on the subject of mis-judgments, how depressing it is when a gifted new writer emerges to almost complete silence. That’s what happened this year to Vivian Hopkirk’s Meditations of a Flawed Groom. It deserves to be celebrated, not ignored.

Back to top

Lisa Catherine Ehrich

Social Alternatives, Vol. 15, No. 4, October 1996

Meditations of a Flawed Groom is a very complex novel. Essentially it is the story of a man who spends three days in a Sydney jail as a result of some unpaid fines and disorderly conduct. Stephen West, the main character, is a poet and philosopher. Among other things, he expounds on various topics such as religion, art, history, society, and metaphysics. The reader is very quickly introduced to his unbridled imagination and his philosophical quest for understanding the nature of humanity.

The book is divided into four main sections, and each section introduces a new inmate who spends a short stint in West’s cell. Each of these characters is colourful - from Morris, the Aboriginal junkie and thief, to the brilliant-minded derelict who is able to hold his own with West when it comes to intellectualising. However, the reader is prevented from developing any empathy for the inmates, because the author’s convoluted language and cryptic statements act as a barrier.

The final part of the book marks a dramatic and unexpected shift in pace, language and style. Whereas the first three chapters rely heavily on overused metaphors and artificially flowery language, the final part of the book is refreshing in both its content and language. It is as though the author decided to give up on trying to impress the reader and just got on with the job of writing. The change in style is so great, it is a little disorienting.

It is in chapter four that Hopkirk becomes the writer of advanced ability that he only pretends to be in the earlier part of the book. He shines through with affection as he narrates his childhood with a keen and cynical eye. His recollections are interrupted by the arrival of another inmate who shares one night in his cell. The two men develop an instant rapport and exchange humorous stories. The stories are delightfully refreshing and light-hearted. The book concludes with West’s release from prison.

In fairness to Vivian Hopkirk he has set himself an almost impossible literary task. To write seriously a philosophical and poetic novel that can maintain a gripping narrative throughout is something that only the likes of Genet or Sartre could accomplish. However disjointed the first part of the book, the second part improves dramatically.

The author’s talent is defined without question at the end of the book. Hopkirk is an important writer though one cannot help but feel cheated at having to wade through so much obscurity at the beginning of the novel to get the rewards at the end.

Back to top

Musecrits

Robert Umphelby

Muse, No. 156, October 1996

Meditations of a Flawed Groom jumps upon the reader’s senses with the first word and never takes breath. With an almost euphoric mien Vivian Hopkirk’s first novel describes his deliberately induced stay in a Sydney jail and its impact on his philosophical and poetic mind. His vision draws constantly on the likes of Camus, Kundera and Solzhenitsyn for quotation and guidance and combines with his own words to create a novel of very heavy reading. The language of Hopkirk’s novel is dense with description and creates such a vivid dialogue of a mind agonising in jail, it is hard to believe it is not deaf with self-possession. This is not to say Vivian Hopkirk does not wield a mighty style of prose, just that at times it takes on a mind of its own that it is so strong it loses credibility in descriptive overload. Meditations of a Flawed Groom’s dense prose is hard to read and is really only for those who are patient and can enjoy the complexities of a philosopher’s mind in the poetic.

Back to top

ISBN 1876044039

Published 1995

149 pgs

$19.95

Meditations of a Flawed Groom book sample

Back to top

part one:

the descent

10 sections

part two:

manoeuvring among the embryo angels

5 sections

part three:

the blue guitar

5 sections

part four:

the wandering protagonist

4 sections

Back to top

Reviews

Comments by Alex Skovron

October 2009

I enjoyed Meditations of a Flawed Groom immensely.

I found it rich, colourful, dense, intense – a novel of ideas, an exploration of consciousness, with some splendid poetic imagery and exhilarating prose. At the same time it is an act of storytelling, and a relay of stories within stories – as in (for instance) the accounts of John’s adventures, or the Socratic dialogue with the dero. I liked your unabashed use of richly-charged, sometimes unusual vocabulary – though I felt that at times, like your hero, you are ‘in the habit of super-enciphering your sentences’....

In sum, I was impressed by your talent, and wish you success.

Back to top

Books and Writing

Geoff Page

Radio National, Broadcast February 1997

Clearly autobiographical in many, but not all, ways, Meditations of a Flawed Groom is a daunting book to review. As with most autobiographies one feels that in some sense one is reviewing the author rather than the work. In the book’s blurb we learn that Vivian Hopkirk is a nephew of the painter Brett Whiteley and it is not a total surprise to see that the late painter is hagiographically offered as a character in the novel. We also learn that Hopkirk is a poet and it is no surprise to see that the book’s narrator, Stephen West, is also a poet. The publishers also inform us that the book’s basic situation, a short stay in jail,has also been an experience of the writer. Given this extra-literary information we may proceed to the novel itself.

The narrator, Stephen West, in the course of a three day stay in jail, converses with, or listens to, a succession of cellmates: a young Aboriginal man called Morris, a philosophical derelict who is heavily into metaphysics and a painter who is an extraordinary raconteur. Occasionally he hears disconcerting activities in the corridor outside and is from time to time abruptly visited by the warders. In between there are various flashbacks, as for instance, to the narrator/author’s childhood and his parents’ marriage break-up, in which Brett Whiteley himself seems to have played a benignly facilitating role.

The style of the book ranges wildly from large slabs of indigestible philosophical dialogue (such as were almost never spoken, even by Socrates and his students) to humorous and highly engaging tall tales from the painter’s travels in Europe. Significantly the later are not from the mouth of Stephen West who seems to have had a terminal overdose of polysyllables and will never use two simple words when one arcane one will do. West himself explains this preference, though not necessarily convincingly. ‘As a rule’, he says, ‘one must be careful not to speak too mysteriously in the English tongue, particularly in the Antipodes, for fear of a smack in the mouth.’ One excerpt from the ‘dero’ sequence illustrates what he means. ‘In other words,’ says Stephen West, ‘God and the Cosmos are synonomous. God evolves. This life ensures that we begin at the darkest beginning and find our way in the gradual realization that we are responsible, not only to our selves, but the fortunes of all existence: to God.’

‘Hmrnmm,’ said the dero. ‘You certainly are a crack metaphysician. I admit that I like your style. Of course, you know what Albert Camus would say.’ Hopkirk, via Stephen West, may indeed by a ‘crack metaphysician’ but whether he’s a true novelist is less certain.

The problem with most of this book is that it really asks too much of its reader, especially in the opening sections. The narrator often seems pompously grandiloquent and the texture of both narration and dialogue is more or less impenetrable. One needs a kind of protestant self-discipline to persist and I was encouraged only by skipping ahead and noting that some of the later sections were rather clearer and so forced myself to go back and work my way slowly forwards again into those more open pastures.

Among the more congenial of such expanses is Hopkirk’s account of his childhood in New Zealand and the breakup of his parents’ marriage. The narrator says of his mother at this point that ‘she was proud and yet somehow abandoned by the extraordinary fame of her brother, who was, until he perished alone in a motel on the South Coast of New South Wales, one of the most remarkable men ever to pace the earth.’ Although this was not the universal view of the critics who reviewed Whiteley’s 1995 retrospective it is clear evidence of the artist’s heroic status in his nephew’s eyes, a view further confirmed by the commanding assistance given by Whiteley to his sister in giving her husband the bad news. ‘Brett was straight from the hip: ‘Man, we’re here to break your heart, and you have to accept it. It’s your fate, you’ll have to be real big. Fran is leaving you for this man, they are in love, and they are going to live in London. That’s the story, that’s the way it is and I have come a long way to tell you this.’

Another of these more open pastures are the tales told by his third cellmate, John, a painter, who is in overnight on a charge of ‘asleep and disorderly’ following a drunken night out with a woman that went badly wrong somewhere. The painter leaves Stephen West (and the reader) highly entertained (and mercifully speechless) with several tales of wild times in Europe with other Rimbaud-style artists and their women. The scene shifts considerably - France, Greece, Italy and Ireland - but perhaps most memorably to a plane trip in New Guinea with a drugged wild boar who wakes up in mid flight.

The novel ends with Stephen’s ejection from jail on the third day and his return to the inner city boarding house described earlier in the novel and tenanted by people of various sexual inclinations and no less strange than West himself. What the average reader will have made of Hopkirk’s novel by this stage is hard to say. Some, like the narrator, may be groggily relieved at their new freedom. Some will consider, with some justice, that they have wasted their time. Still others will feel they have been in the claustrophic presence of a powerful but anarchic talent which has not yet quite found its true metier. In any event, Vivian Hopkirk and his Meditations of a Flawed Groom will not slip blandly from their memory.

Back to top

shorts

Sydney Smith

Australian Book Review, No. 188, February/March 1997

These are the ruminations of one Stephen West during a three-day stint in prison. Groping through the murk produced by the author’s over-use of the thesaurus and under-use of the dictionary, I encounter Stephen’s co-inmate, an Aborigine from Redfern,who recounts his history of drug abuse and crime, which sets Stephen off on a line of reflection.

A people for whom we have inherited the responsibility of those who assumed to change the world, into which we have invaginated ourselves...

A page of this exhausted me. And it went on: ‘What a centrifuge of terrors and absence of communication or belief in the ductile holiness of a child.’ Good grief.

Look - this is a bad book. The English is usually deranged; the philosophical bits are trite or poorly reasoned; poetry and humour don’t exist in it. The recurrence of certain words: ‘vanity’ and ‘invaginated’ are two examples, gave me a picture of Stephen and his creator which I’m sure the latter did not intend. So that, when Stephen announced, ‘Estrange the child, and you estrange it from itself,’ I knew with certainty he had no idea the truth he spoke.

Back to top

Best books of ’96

Rodney Hall, novelist

The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 November 1996

My year’s reading has been dominated by Roger Milliss’s magnificent history of the Australia Day massacre of 1838, Waterloo Creek. Pauline Hanson ought not to be allowed back into Parliament until she has read all 750 pages. Milliss’s great achievement is to marshal a wealth of facts into a story of breathtaking drive and moral urgency. A thoughtful Christmas present for John Howard, too.

I have just begun The Glade within the Grove by David Foster. It is already proving to be Foster’s characteristic mix of comedy and erudition - massive, quirky and very good. I am yet again astounded that he is not more celebrated. Too much adulation is squandered on lightweight novels masquerading as literary works.

While on the subject of mis-judgments, how depressing it is when a gifted new writer emerges to almost complete silence. That’s what happened this year to Vivian Hopkirk’s Meditations of a Flawed Groom. It deserves to be celebrated, not ignored.

Back to top

Lisa Catherine Ehrich

Social Alternatives, Vol. 15, No. 4, October 1996

Meditations of a Flawed Groom is a very complex novel. Essentially it is the story of a man who spends three days in a Sydney jail as a result of some unpaid fines and disorderly conduct. Stephen West, the main character, is a poet and philosopher. Among other things, he expounds on various topics such as religion, art, history, society, and metaphysics. The reader is very quickly introduced to his unbridled imagination and his philosophical quest for understanding the nature of humanity.

The book is divided into four main sections, and each section introduces a new inmate who spends a short stint in West’s cell. Each of these characters is colourful - from Morris, the Aboriginal junkie and thief, to the brilliant-minded derelict who is able to hold his own with West when it comes to intellectualising. However, the reader is prevented from developing any empathy for the inmates, because the author’s convoluted language and cryptic statements act as a barrier.

The final part of the book marks a dramatic and unexpected shift in pace, language and style. Whereas the first three chapters rely heavily on overused metaphors and artificially flowery language, the final part of the book is refreshing in both its content and language. It is as though the author decided to give up on trying to impress the reader and just got on with the job of writing. The change in style is so great, it is a little disorienting.

It is in chapter four that Hopkirk becomes the writer of advanced ability that he only pretends to be in the earlier part of the book. He shines through with affection as he narrates his childhood with a keen and cynical eye. His recollections are interrupted by the arrival of another inmate who shares one night in his cell. The two men develop an instant rapport and exchange humorous stories. The stories are delightfully refreshing and light-hearted. The book concludes with West’s release from prison.

In fairness to Vivian Hopkirk he has set himself an almost impossible literary task. To write seriously a philosophical and poetic novel that can maintain a gripping narrative throughout is something that only the likes of Genet or Sartre could accomplish. However disjointed the first part of the book, the second part improves dramatically.

The author’s talent is defined without question at the end of the book. Hopkirk is an important writer though one cannot help but feel cheated at having to wade through so much obscurity at the beginning of the novel to get the rewards at the end.

Back to top

Musecrits

Robert Umphelby

Muse, No. 156, October 1996

Meditations of a Flawed Groom jumps upon the reader’s senses with the first word and never takes breath. With an almost euphoric mien Vivian Hopkirk’s first novel describes his deliberately induced stay in a Sydney jail and its impact on his philosophical and poetic mind. His vision draws constantly on the likes of Camus, Kundera and Solzhenitsyn for quotation and guidance and combines with his own words to create a novel of very heavy reading. The language of Hopkirk’s novel is dense with description and creates such a vivid dialogue of a mind agonising in jail, it is hard to believe it is not deaf with self-possession. This is not to say Vivian Hopkirk does not wield a mighty style of prose, just that at times it takes on a mind of its own that it is so strong it loses credibility in descriptive overload. Meditations of a Flawed Groom’s dense prose is hard to read and is really only for those who are patient and can enjoy the complexities of a philosopher’s mind in the poetic.

Back to top