|

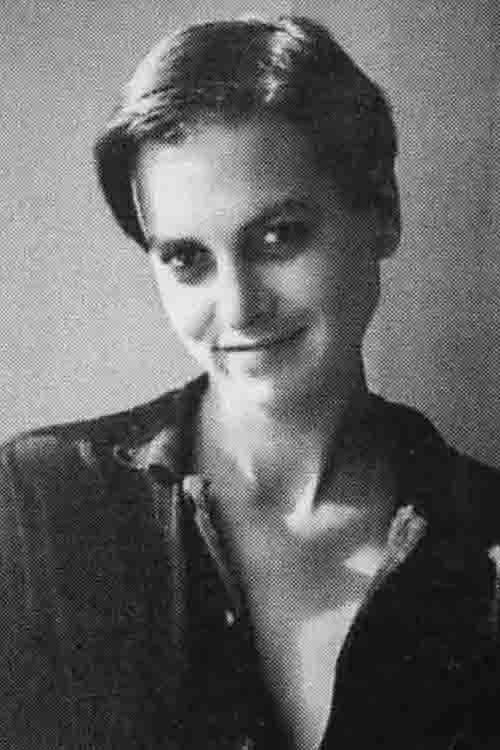

Jordie Albiston 1961- 2022  Jordie Albiston reading from The Hanging of Jean LeeORBITUARY Melbourne-based poet Jordie Albiston has died, aged 60. Born and raised in Melbourne, Victoria, Albiston studied music at the Victorian College of the Arts and received a Doctorate in English from La Trobe University. With a career spanning over 25 years, Albiston was the author of 17 books. Her first poetry collection Nervous Arcs (Spinifex) won the Mary Gilmore Award, and her fourth The Sonnet According to M (John Leonard Press) was awarded the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry at the 2010 NSW Premierís Literary Awards. In 2019, Albiston won the Patrick White Award for her contribution to Australian literature. Albiston was a finalist for the 2021 Melbourne Prize for Literature, and her most recent collection Fifteeners (Puncher & Wattmann), posthumously won the John Bray Poetry Award in the 2022 Adelaide Festival Awards for Literature. Puncher & Wattmann publisher David Musgrave writes: ĎJordie Albiston, who died suddenly at the age of 60 on February 28, will be remembered as one of Australiaís great poets. During her career she published 13 poetry collections, three poetry collections for children and a poetry textbook, which is widely used. ĎShe pioneered the documentary form in Australian poetry with Botany Bay Document (1996) and The Hanging of Jean Lee (1998). Her landmark collection The Fall (2003) established her as a poet with a wide range, and also showcased her deep interest in form. This was furthered in virtuosic manner in Vertigo: A Cantata (2007), which was informed by her accomplished musicianship (Jordie studied at The Victorian College of the Arts, specialising in flute) in a highly innovative way, and The Sonnet According to M (2009), in which her interest in the sonnet form was played out to a highly inventive degree. Her work was bold, brave, and continually broke new ground, often in playful ways, but always brilliant. ĎShe was a modest and unassuming person and was deeply uncomfortable being the centre of attention, completely withdrawing from public events in the last few years. She was deeply generous to other poetsí work and was a mentor to, and supporter of, many emerging poets. Her Selected Poems will be published by Puncher & Wattmann later this year and will include poems from the several manuscripts she was working on at the time of her death. She is survived by her husband Andy, children Jess and Caleb, and their partners and grandchildren.í Poet and critic Thuy On of ArtsHub writes: ĎShe was a disciplinarian in her craft, an elegant classicist who nonetheless knew how to bend and break the many constricting rules of rhyme, metre and line space for resonance and impact. Throughout her entire oeuvre, the reader bears witness to Albistonís nuance and sensitivity and sees how her musical background reveals itself in cadenced lyrics. Her flair for experimentation meant that no new book resembled the previous effort. ĎThrough her biographical narrative pieces, Albiston touched upon historical events, re-imagining the stories of the last woman hanged in Victoria, the women settlers of Port Jackson and Botany Bay, WWI soldiers in Victoria and an Antarctic adventurer. But Albiston also looked inwardly and reflected upon perennial, evergreen themes of domesticity, desire, and loss set in contemporary times. ĎHer febrile interest in mathematics and chemistry meant that her poetry was often exacting in its form. As for their contentsóitís impossible to pin down her interests. How can one do that for a poet who roamed so freely? Who else but Albiston could harness the periodic table as a trope to explore the fundamentals of love? ĎAside from her plying her writing skills, Albiston was also a manuscript assessor, proof-reader, editor and mentor. Thereís been a chorus from fellow poets on social media lauding her work and from others whose careers she has nurtured over the years.í |

|||||||

Jordie Albiston has published seven collections of poetry, her first being Nervous Arcs (Spinifex, 1995) [Co-published alongside Diane Faheyís The Body in Time], winner of the Mary Gilmore Award, My Secret Life (Picaro Press, 2002), The Fall (White Crane Press, 2003), Vertigo: A Cantata (John Leonard Press, 2007) and the sonnet according to Ďmí (John Leonard Press, 2009). She was shortlisted for the Victorian Premierís Literary Awards and the C.J. Dennis Prize for Poetry in 2003 and for the New South Wales Premierís Literary Awards and the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry in 2004. She was joint winner of the Wesley Michel Wright Award in 1991, and has also won the Dinny OíHearn Memorial Fellowship. She has a PhD in Literature, enjoys cooking, being in the ocean, and long walks with her dog, Jack.

Interview with Jordie Albiston Kate Middleton Famous Reporter, No. 24, December 2001KM : You once wrote an article that, in part, responded to a young reader who had asked you why you Ďnever write poetry about yourselfí; at the same time, I remember Dorothy Porter once referred to her verse novel Akhenaten as her most autobiographical work. Do you feel that in working with the structure of other peopleís stories, specifically in your last two books, it is easier to take risks, or write personally? JA : Well, Iím going to have to

echo

Dorothy, because I donít often write about my own life as

such - you know, ĎI

went to the shops, ran into Kate, etc...í For me, those last

two books are

about me as much as theyíre about the subject at hand: I see

it as a question

of metaphoricity, and in the case of a full-length book concerning one

person,

event or theme, the metaphor is simply extended. Itís the

same principle as

writing a metaphor of self into one poem or one single image, but

extended. How did you come to choose those

particular stories? I was originally going to concentrate

my doctorate on the first fifty years of white settlement at Obviously you have an academic

background - you say that you didnít consider it much of a

leap from your PhD

to a book of poetry. How does your academic background inform your work? I think studying has given me a sense

of discipline and precision as a writer. When I sit down to write

poetry, Iím

disciplined: I turn the computer on, take the phone off the hook, shut

the

curtains, and focus. I didnít used to be such a focussed

person... Also, in the

academic world, you canít afford to make many mistakes as

such, or write

assumptions into your work: everything has to be checked. You have to

learn to

retain the spelling of a particular name, or what year such-and-such

happened,

or was said, or written. You have to. And hopefully that precision

feeds back

into the poems. Academia also taught me how to research: where to

begin, how to

go about it. Recently your work has begun to take

off in different directions from your last two books - last year there

was the

one-woman show of The

Hanging of Jean Lee at La Mama, and now

both Botany Bay Document and

The Hanging of Jean Lee are

being written as operas. How do you feel about the fact that your work

is being

taken to different audiences in this way? Well - this is a difficult question,

because youíre one of the composers! Any artistic act that

evolves from some

writing Iíve done has little to do with me, in its new form,

really. My job is

finished. I donít feel that Ďmy workí is

being taken to different audiences:

itís the stories themselves being taken to different

audiences in different

ways, and itís a layering kind of thing. The ABC also did a

radio dramatisation

of Jean Lee, and yes, theyíre my words, but itís a

dialogue, it goes on. If

another artist picks it up, itís going to affect people

differently depending

on how itís constructed. Because these stories are historical

- You have a background yourself in

music. How has that influenced your work? Totally. I donít think

Iíd be a poet

at all if I didnít have that background: the two are so

intermeshed. I learned

piano and then flute as a girl and ended up at the College of the Arts,

although I enjoyed flute itself less and less as time went by.

Iím a cellist by

nature, although I donít play the cello! But more than that I

think itís been listening

to music all my life: classical music was always playing as I grew up.

I

starting off liking people like Lutoslawski and Janacek, and from there

found

my way to Hindemith, Webern, Ligeti, and then I went backwards, and

Iíve only

really begun to appreciate composers like Mozart and Schubert in the

last

fifteen years or so. Beethoven and Bach were always there, of course -

and Bach

is my favourite composer of all - but some others have taken me a long

time to

engage with. And in terms of influencing my writing, Iím

interested in that

fourth dimension of poetry, the actual physical and psychological

connections

between words and lines: and thatís similar to orchestration

in music. I mean,

with music, all youíve got are musical notes and silences.

Thatís it: theyíre

your tools. Notes and silence. And with poetry, itís words

and spaces. My poems

are fairly structural, and I know Iím a bit formalistic for

many peopleís

tastes, but I do believe in things like unity, balance, symmetry... a

poem

doesnít necessarily have to look visually

symmetrical to please me as a

reader, but there has to be a very particular sense of organic order

and

cohesion: a beginning and an end, and a relationship between every part. You work a lot with form. How much do

you use traditional forms, or create your own forms - and what

advantage do you

see in adhering to those forms in your own work? Well, thereís nothing

without form -

thereís no poem without form. Content and form:

theyíre the only two elements.

And poems simply about how someoneís feeling donít

really appeal to me as a

reader. Thereís got to be some structure there, in terms of

both content and

form. And personally what I like about form is that for every

restriction

offered, thereís always a liberty as well, hidden away in

there. Thereís no

reason to be scared of form, because for every rule thereís a

window or even a

whole tesseract that opens, and itís that kind of movement

that I like, that

kind of momentum... Obviously the rhythmic aspect of your

poetry is very important, and that does get quite complex at times. I

remember

once when I was talking with someone about my own work, they suggested

that I

go through my various writing stages, and that the final thing I do be

a

rhythmic rewrite, to make sure the rhythms fall into place. What sort

of

process do you go through to write a poem. Are there those stages? Do

you start

with the idea of the rhythm? Thatís a good question. I

tend to

start with a shape, actually, an architectural kind of figure.

Thereís a shape

I want to express. Itís this thing I want

to make, and then I look for

the right content that might suit that thing. Sounds a little boring,

doesnít

it? Not very emotional - but for me, the passion is in the maths.

Rhythms

themselves come fairly naturally. I lean to the triple meter side of

things,

but I enjoy enjambment and other ways of upsetting the apple-cart... What kind

of drafting process do you go through with a poem? I write straight onto screen, and

always have. I only use paper if Iím stuck without my

computer! And as far as

the drafting process is concerned, I donít print off until

Iím pretty sure what

Iím doing is Ďrightí. It never is, of

course, but it means I do print off at a

late stage. I donít keep working notes or drafts, I prefer

not to leave many

traces at all. I donít have journals (or at least only blank

ones!), I barely

write letters, and itís the same with drafts: they hit the

bin as soon as Iím

finished with them. Do you have any kind of writing

rituals you go through? You mentioned before that you write straight

onto the

computer, and youíve also told me before that you start the

day reading

biography and poetry; do you have reading and writing schedules that

you follow

when you are writing? Well, itís a bit different

being on a

grant rather than working fulltime at the moment, because Iím

able to make

those rituals for myself, timewise anyway. My writing days are

Thursdays,

Fridays and Saturdays - only three, but theyíre full days,

often sixteen-hour

marathons. The rest of the week is pretty much filled with reading,

cooking,

teenagers, the business of life. Occasionally I make a couple of notes

between

Sunday and Thursday, but most of itís happening in my head

and I donít turn on

the computer or pick up a pen. And I do read biography everyday -

thatís my

nurturing source. Any particular biographies? Anyone - almost anyone. When I go into

bookshops, I head straight for the biography section. Whatever.

Churchillís letters.

Anybody. Just to see where they went wrong, where they went right, how

it was

for them. They donít need to be artistic, although often they

are musicians or

painters or writers, but itís certainly not just those

people. Itís anybody

really. Iíve been reading about Leonard Bernstein, and Darwin

recently.

When did you start writing? When I was little - around

kindergarten time. Mum and Dad still have poems I wrote when I was four

or

five, and one grandmother used to mark them for me out of ten! Then

writing was

replaced by music for probably fifteen years, and I really

didnít start again

until I was about twenty-eight. That was an epiphanal year, and poems

began to

come. Those early pieces are long trashed, but there was that

recognition, that

feeling of ĎThis is where I belongí. So I kept on

going. Can you note any particular

influences, either in your early work, or what youíre doing

now? Among writers? Itís funny, I

feel some

prose writers have had a big effect on me, which may not make immediate

sense

if weíre talking about line turns, but thereís

Janet Frame, Paul Auster, Toni

Morrison. The Bible is a good source of inspiration, and has been

influential -

the actual language of it, not just the stories - especially the King

James,

its particular syntax and choice of words. And of course Emily

Dickinson, the

Americans. Bob Dylan. Other than that, Iím pretty much

interested in what

anyoneís doing. The Australians I like to follow would

include Peter Porter,

Rosemary Dobson, Mark OíConnor, Jan Harry, Jenny Harrison,

Alex Skovron... this

is hardly an exhaustive list. More recently, thereís been

Peter Minter, Rebecca

Edwards...Iíve been reading Mark OíFlynn lately...

you go through phases, where

you just really love one writer and read all their books... I tend not

to read

much poetry as Iím getting toward the end of the week and

preparing to write

myself, because it is easy to be influenced, and Iím much

more strongly my own

writer when Iím isolated from other poets. I mean I live with

a poet - youíve

got to keep certain barriers, otherwise it all starts bleeding into

itself, and

you end up in a big mess of words. Have you ever written creatively in

other forms? You mentioned that prose is an influence on your poetry -

have you

attempted prose writing? Or are you interested in doing so? I wrote a terrible novel when I was

about twenty-two, which you will never see. That

showed me I am not a

novelist, definitely! Iíve also written a couple of short

stories. One of them

was in an early Picador New Writing, but I could

see afterwards it was

simply a long poem put into short story form. I tried a few more -

maybe four

or five - but they just didnít work. No, Iím just a

poet. I love poetry as a

genre because you have to pay so much for every word that you use.

Itís a very

costly literary exercise, as opposed to writing a novel. I mean, a poem

is so

economically driven. I guess thatís where the maths comes

into it for me,

because every single word has to have a relationship with every other

word, and

somehow youíve got to write music into it as well, if you

can. Itís such a

challenge. Each poem to me is an immense event, and it can also be

draining,

extremely. How long does it take you, generally,

to write a poem? Well... from the first idea of it,

probably about six months. And from the first turning on of the

computer,

probably sixteen to twenty-four hours, which may be spread over two or

three

weeks. Iíve always worked like that. Any poem will take a

long time to gestate,

because I donít want to type anything until Iíve

almost got the thing in my

head. Even on computer, even on a screen of lights, as opposed to a

piece of

paper - it seems so concrete, that first line. I work from beginning to

end,

with the idea of a shape and the idea of a story in my mind. I never

start with

the last line, or the middle image... itís the first line

thatís going to

dictate to a large extent the rest of the poem. Joan Didion once said of her novels

that her first sentence has to be perfect, because everything grows

from that,

and once youíve got your first paragraph written,

thereís no going back. I agree with her! And of course

itís

more compressed with poetry - youíd be talking about your

first word as

important, your first phrase, and after your first sentence there being

no

going back... And itís a question of respect as well, of

honouring the poem.

What is trying to come out on the page? You think in your head

ĎI want to write

a poem in Italian quatrainsí or whatever, and

youíve a vague idea itíll be

about a page and a half long, and you want to cover this sort of

ground, and

thatís about all you start with - and then this completely

different animal

comes out of the computer, which has barely anything to do with your

original

idea, and you think ĎWhere did that come

from?í... It comes down to

respecting and honouring the poem itself. Itís the

Michelangelo thing:

chipping, tapping away, seeing whatís inside there, trying to

help get it out. In the past you have taught Creative

Writing/Writing Poetry at a tertiary level; how do you feel about the

writing

courses that are available everywhere? Do you feel that they are useful

for the

students? Do you think that writing is something that can be taught? I think they are useful, but I think

the nature of their usefulness could be

questioned. Obviously, you get a

group of students entering a writing course, and theyíre

going to be writing

differently at the end of that course, because of what

theyíve been exposed to.

Yet they could expose themselves to the same world by simply reading

and

writing! Because thatís what it comes down to,

thatís how you learn to create

poems. At the same time youíve done

manuscript assessment, and participated in formal mentorship schemes on

a

one-to-one basis. How does this form of teaching/guidance for less

experienced

writers differ from the classroom situation? In all ways. Itís

one-on-one, itís

dialogic, youíre not having to deal with maybe two or three

talented

individuals in class, and then having to pitch your teaching to try to

work

with those people while at the same time doing the right thing, and

involving

everyone else. It can be a difficult juggling act, especially when

youíve got

up to twenty-eight students in one class, and theyíre

three-hour sessions, and

everybodyís intense, everyone wants their poem looked at, of

course... Thatís

what you bypass in a one-to-one situation. One-to-one you learn as much

as you

teach. And teaching-by-correspondence and manuscript assessment are

different

situations again, because you donít get to meet the person,

donít know who they

are, and they donít know who you are. Those are my favourite

teaching

situations! Do you think of yourself as a feminist

writer, especially given that both Botany Bay Document and The

Hanging of Jean Lee are working with

untold stories of Australian women? No, I donít think of myself

as

anything particular at all. Iím pretty much anti-political. I

write about women

because I am one, and thatís where the story stops.

Itís really hard to write

about a man, engage with the male heart and mind, when youíve

got almost no

understanding of men at all: and thatís me. I donít

understand those people

over there, those men, even though I have a partner, a son, a father, a

brother. I barely understand women! But itís nothing to do

with holding a flag

and being a feminist. Itís more to do with truth, and

silence, and the fact

that many womenís voices have been silenced. If I

wasnít a woman, I donít think

Iíd be writing about women, but Iím not

specifically a feminist. Can you tell me a little about what

youíre currently working on? Yes!

Itís a collection of chained verse - sestinas, pantoums,

villanelles, ottava

rima - all types of chained verse. Sometimes Iím working with

complete forms,

although at other times I may use just one isolated device - like an

anaphoric

structure or something - in a poem. Part of what Iím trying

to do is help

develop some of these forms, help - along with numerous other poets -

challenge

and reinforce them, help them to hold what we need to express right

now. I

mean, villanelles were written 400 years ago, and they still have a lot

of

energy, but how do you apply that energy in the

early twenty-first

century? I feel we have a responsibility to move within some

of these

forms, if theyíre tractable, if that can be done. And also,

Iím trying to

develop some kind of Australian aesthetic for certain chained verse

forms.

Earlier this year I spent time going out and counting branches in the

bush,

timing waves at the ocean, and so on, looking for patterns I could

weave into

the work that were specifically Australian patterns, because we do not

have a

European, or American, or African landscape... I pretty soon had to

accept that

almost everything in Its

working title is The Fall. Back to top | ||||||||