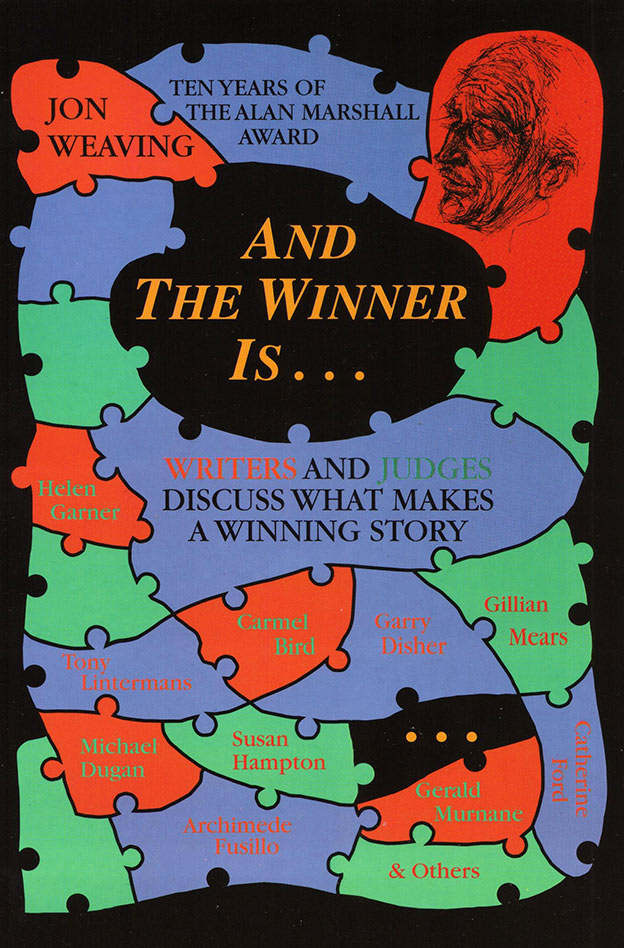

These are collected

stories by the

winners, since 1985, of the Eltham Alan Marshall Short Story Award.

Introducing each year’s winners are bio-notes on the writers,

their

comments on the experience of writing, and potted tutorials by Jon

Weaving on some aspect of the short story form. A few winners were left

out as Jon was unable to find them to gain their permission for

inclusion. The little tutorials seem adequate as signposts pointing

newcomers in the right direction. I agreed with all his points, and

heartily agreed with his piece on the narrative connect-a-bits: he

said, she answered, it howled forlornly.

The stories themselves varied widely as to approach and content. I

liked Tony Lintermans’ ‘The Great Man and Three

Chickens’ for its

braggadocio similes, Catherine Ford’s

‘Empty’ for its unforced delivery

and the beauty of its structure, and to Patrick West for

‘Cruelty’,

biopsy of a deranged mind, I gave a big fat elephant stamp. Special

mention to Adam Hinkle’s funny prose cartoon ‘The

Haircut That Changed

My Life’.

Back to top

Jon Weaving

Once, as a child, I was determined to cook something. It was going to

be a cake, that much I knew, but I had no idea what kind it was

possible to make because I didn’t know what was in the

cupboards. I

remember snuffling under benches, each thing I came across trigering a

whole new direction of possibilities that I laid in a huge and very

messy array across the kitchen. My mother quite calmly returned the

lot, replacing it all with a single canister of flour which, she

pointed out, was the basic ingredient without which there could be no

cake.

Dear Helen,

Back in 1987 you judged the Eltham Short Story Award, and at the risk

of being seen as living proof of our pasts loping along behind and just

waiting for a chance to haunt, I’m hoping for a small amount

of help

with a book I’ve been commissioned to write.

When I wrote this opening paragraph of a letter to Helen Garner I did

so with more than a little trepidation. Not only was her latest book

The First Stone

turning sods of controversy, hijacking her name from

the literary pages into those of the general news and, quite obviously,

keeping her extremely busy, but here I was asking her to be flour for a

cake of someone else’s making.

Which is exactly what I would have to ask of thirty-one busy writers in

total, both winners and judges and all of them, collectively, the

central ingredient without which this book would be impossible.

The response I got to my initial requests was quite amazing. Eighteen

of the twenty-one award winning writers agreed immediately to allow

publication of their winning stories and to be interviewed about

themselves and their writing. The other three have, I’m sure,

simply

dropped off the edge of the planet and could not be contacted. Of the

eleven different writers who have judged the Eltham award, one (Lance

Loughrey, co-judge in 1985/6) was untraceable, but again the response

from the others was that they would be happy to be a part of this book.

Which meant at least

that there could

be

a book.

But the problem of what it would actually be

about still

skittered, off

from the edge of me and just out of reach.

Again from my first-approach letter to Helen Garner,

I would like to do a book about writing, about awards, about their

value, the subjectiveness of art, judging (and what judges look for)

and about some of the technical/craft aspects of short story writing

that are used to evoke specific images and responses. A book about the

winners and judges themselves, from their development as writers down

to the way in which they physically work.

I don’t imagine the finished product to be a mongrel cross

between a

‘how-to’ manual, the Personal Best andYacker series,

but I am convinced

that a book like this, while concentrating on this one award (and

therefore meeting Eltham’s requirements for a celebratory

publication)

would be a hell of a lot more interesting to write and to read. Christ!

I never was any good at just taking the money and doing a runner along

some easier path!

This was the book’s ‘definition’ then,

presented in basically the same

way to everyone I approached, but if I could spell the sound that is

made when a cold shiver runs up one’s spine and escapes the

mouth as an

expression of foreboding I would write it here.

For it must have appeared that I had a clear understanding of what this

book was going to be, its direction and purpose. The reality was quite

different. Other than the broadest possible definition of

a book about

writing and awards, the thing I seemed best able to define

was what the

book

wouldn’t

be. And the more I thought about that the less

accurate

and likely even that seemed.

Before me, in flashing neon, was a single line from Jenny

Lee’s 1992

Judge’s Report in which, contextually, she touched on the

limits of an

editor.

What I cannot do, she said,

is give purpose to a work that

has none.

Purpose - It became obvious to me that defining one at

this stage,

before interviewing the writers, would be a mistake. To do so would

focus the direction of my questions too narrowly, limit possibilities

and risk leaving unearthed gems as just that.

So I asked

everything

and will be eternally indebted to those writers

who not only put up with that too-much, too-broad, somewhat

directionless and unprofessional approach, but who also gave of

themselves so freely and with such care and effort as to make this book

possible.

Even now I’m not sure why this approach made me so

uncomfortable.

Normally I’m perfectly happy to start a piece of writing from

one

simple, broad idea, cruising along a myriad of tangents, producing

many,

many

more words than I could ever use and eventually stumbling

across a purpose. In fact it’s only ever after that

‘tour of discovery’

that I feel I have any sort of grip on ‘purpose’ at

all.

But in this case, despite the completion of interviews, the sorting,

sifting and weighing of gems, there was still no

clear direction to

be

seen. I was back in my mother’s kitchen, surrounded by a

strew of

ingredients, but unnervingly bereft of the single, workable and

reassuring recipe that I thought by now I should have discovered. I

felt almost fraudulent at having asked so much of all those who had

agreed to help with the book.

It was all so messy.

In fact I probably tried for that ‘tight’

definition of purpose a dozen

more times, reading again and again the responses to my long lists of

questions before I spotted the hole I was in for what it truly was: A

cage. Quite simply, I was beating myself over the head searching for

one reason

for this book’s existence,

one purpose behind

reading it and

such singularity just didn’t, couldn’t and

shouldn’t exist. I had

locked myself into one way of thinking, something I have counselled

writing students against time and time again.

So why do we read? What expectations and desires, perhaps subconscious,

are triggered whenever we enter into contact with a writer?

Gerald Murnane expects to learn something of a particular human

experience when he reads a piece of short fiction. Of his judging he

said, ‘I stopped reading many a story as soon as I

had

become convinced that I would learn from it nothing of value to

me.’

Garry Disher talks of being instructed in the craft of writing.

‘I like

to learn to write by reading other writers.’

Michael Dugan says, ‘Insight.’

Achimede Fusillo is concious, when reading, of stopping and taking note

of how a particular thing has been achieved.

Gillian Mears is a little more specific in that she looks at how other

writers structure a book; how the narrative is formed and maintained.

Tony Lintermans talks of his liking for, ‘....stories that

are wells

full of light and wisdom.’

This desire to

learn

something from a piece of writing reared up time

and time again in the comments of writers, from both the

well-established and the emerging and regardless of age. Surely then we

can make the leap to the liklihood that if learning

from a piece of

writing is important to these successful writers, then showing

something through their own work is equally so?

The purpose of this book then? I doubt I could find one more

appropriate than

showing.

The showing of even some of the attitudes,

opinions, preferences, intentions and physical work methods of such a

wide range of Australian writers will, I’m certain, become

‘wells full

of light and wisdom’ for those interested in writing,

regardless of

their relationship with it.

For those seeking the more specific showing of techniques, there are

also ten short sections each focusing on a particular aspect of and

approach to the writing of stories. And of course there is the simpler

but no less important showing of eighteen award-winning stories

themselves - stories to be analysed critically with regards to winning

qualities or, if the reader so chooses, to be read for no reason other

than pure entertainment. Perhaps this purpose of

showing is best

seen

as the provision of a series of doorways through which the reader is

free to remove anything he or she feels may be of value.

I am obviously still in that messy kitchen, only now I’m

convinced it

is the only place to be. If for no other reason than to make me more

comfortable with this I have clipped a sentence from Helen

Garner’s reply to my initial letter and pasted it on the wall.

The book sounds really good - nice and messy - fresh and original -

good on you.

The highlighting is hers, the responsibility, should too much of what

it emphasises stain the pages of this book, is mine.

~

Housekeeping - The Shire of Eltham Alan Marshall Short

Story Award was

first run and won in 1985. Initially established to honour and remember

former Eltham resident Alan Marshall, this annual award of one major

prize for an open section and one for young,

‘local’ writers (the Shire

President’s Award), has actually undergone very few changes.

The most

notable of these would be the increasing of prizemoney and the removal,

in 1987, of ‘entry conditions’ wording which

indicated a ‘popular,

narrative story in the style of Alan Marshall’ was being

sought.

These changes, a long-term financial commitment to the award by the

Shire of Eltham and the organising committee’s early decision

to employ

only the best possible literary names as judges, resulted in the

perception of this prize shifting from that of local to national.

There have also been so very few grumblings associated with the Eltham

award. In ten years and from a pool of nearly three and a half thousand

entries, a total of three letters have been recieved from affronted

entrants. One disliked a particular judge’s reported

comments, another

found the commendation offered him insulting and the third made

accusations of

shamful

copyright breach when her story was not

returned... as per the clearly stated conditions of entry. Of slightly

more interest was the poking forth, in 1986, of what was perhaps the

closest thing to a controversy.

In 1985 co-judges Clem Christensen and Lance Loughrey awarded the open

prize jointly. When in 1986 those same judges again could not arrive at

a point where a single winner awaited them, they decided on a three-way

split of, in effect, a first and two equal second places. The

organising committee of the time however, stated that to advertise one

major prize but not award it, in

two consecutive years, was ‘not a good way to project the

prize’ and

the decision of the judges was overturned in favour of a single winner.

A letter after this date, from Clem Christensen to those organisers,

included the clear message that he, ‘...did not wish to have

any further

dealings with the short story prize.’

As it turned out though, Lance Loughrey simply could not be contacted,

Clem Christensen, despite that letter, was happy to talk to me (though

his ill-health did eventually make interviews impossible) and Clinton

Smith, the award winner judged ultimately by the organising committee

rather than by the judges, said simply, ‘I think the

committee got it

right.’ All in all so very little change and turmoil as to

make any

detailed historical analysis of the award’s development and

management

a complete waste of paper.

As for the stories appearing in this book it should be noted that there

was none of the usual editorial privilege and subjectiveness with

regard to selection and ordering. The omission of three winning pieces

for example (two Open and one Shire President’s Award) was

not a matter

of choice, rather it was a simple consequence of being unable to

contact those particular writers. The decision to present the works

chronologically had, again, very little in common with choice. To do

otherwise might well have implied some order of quality, an order of

quality each reader should be entitled to make for themselves if they

are so inclined.

So the stories are simply gathered according to the year of their award

and preceeded by information on the relevant writers and judges and,

where possible, the winner’s responses to the questions - How

do you

write? What do you find hardest about writing a short story? Why do you

write? These questions were chosen because of our seemingly bottomless

curiosity about writers’ work habits, problems and reasons

and to show

us, in conjunction with the stories, at least a little of each author

before they give voice of a different kind in later sections.

Each grouping of stories is also accompanied by a short chapter dealing

with an aspect of creative writing suggested by that particular

year’s

authors, judges or stories themselves. These comments are not meant to

form a comprehensive ‘handbook’ on writing, they

are prompts, and as with the rest of this book the views

and opinions, unless specifically quoted or attributed, should only be

read as mine.

Of course none of the writers were compelled to even answer my

invitation, let alone answer in a particular way. Some have chosen to

say more than others, either in general or on a specific matter, and in

a very small number of instances chose to say nothing at all. Those

gaps, thankfully very few, that occur throughout this book do so then

not as a result of some judgement of worth, but purely because of

circumstance.

It is also unlikely that these stories would have been each

writer’s

first choice for publication had I asked for either a favourite story

or a standard anthology piece, a likelihood supported by the comments

of more than a few authors but perhaps best encapsulated by Garry

Disher’s reference to his 1985 winning story.

I no longer consider ‘Poor Reception’ to be very

good. It’s not bad,

it’s dependable and worthy enough, but I can do much better

now.

It is this sort of honesty, offered up so readily as both a learning

tool for readers and, in the case of the writers themselves, a

preparedness to be seen rather than merely

presented, that

kept me in

the messy kitchen. It was just... worth it.

There are specific things to be learnt about particular writers and

stories, our desire to ‘know’ is sated, but it is

what they

are.saying,

what they are

showing

us is possible, that is to the fore because the

writers have not so much defined themselves, but rather some of the

ideas and beliefs that

result

in ‘themselves’.

Rather than telling us only that writer ‘A’ thinks

a certain thing, the

unique combination of beliefs, stories, work habits and comments from

young, not so young, well-established and emerging writers provides us

with possibilities and prompts, knowledge and insights, arguments and

questions far beyond the range likely from the views of a single writer

or a collection of writer’s ‘profiles’.

Back to top

And

The Winner

Is...

And

The Winner

Is...