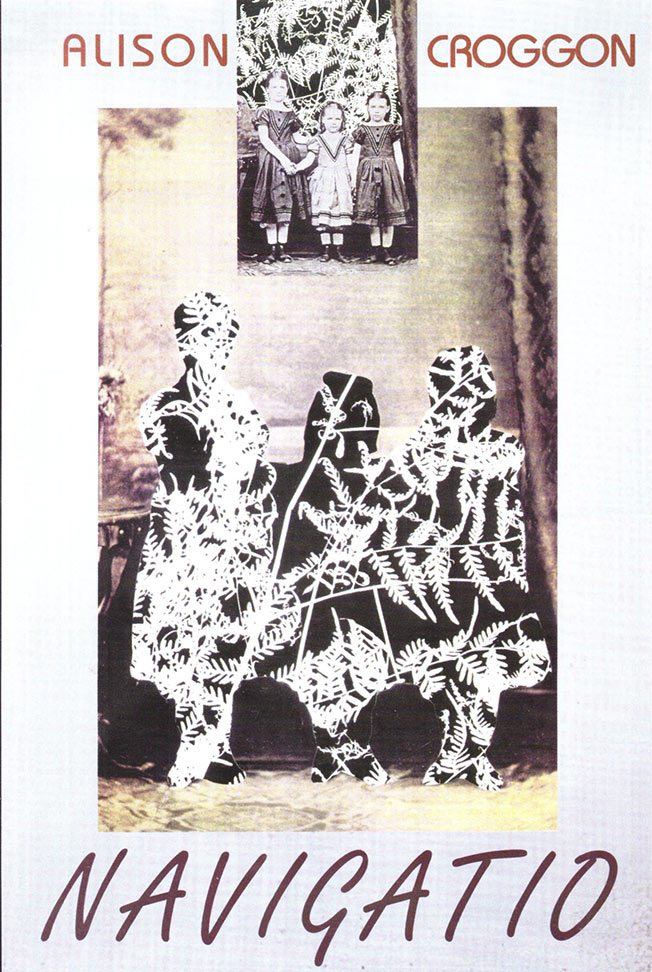

Alison Croggon trained

as a

journalist and her work includes poetry, plays, libretti, translations,

editing and criticism. Croggon’s book, Navigatio, is a

story of her

family’s double migration and an account of a nineteenth

century sea

voyage and arrival. The book is divided into ten different stories, all

weaving past and present history.

The prologue informs the reader of her father:

Navigatio,

a first novel by the talented young Melbourne poet, Alison Croggon, has

also been released by the same innovative new publisher [as for Vivien

Hopkirk’s

Meditations

of a Flawed Groom],

Black Pepper. Like Hopkirk’s

Flawed

Groom, Croggon’s

Navigatio

is also highly

experimental and unorthodox in form. Two stories alternate here; one a

fairly straightforward autobiography, the other a stylistically

adventurous account of what seems to be an analogue for the

author’s

own family voyaging to (or at least towards) Australia in 1869. The two

strands of the novel, if that’s what it is,are decidedly

different from

each other, despite the centrality of the mother/three daughters unit

in both.

The autobiography is a relatively unadorned and presumably accurate

account of the unhappy marriage of Croggon’s parents - and of

some of

the more important highs and lows of her childhood in South Africa,

Cornwall and Australia. Unlike the autobiographies of, say, Sally

Morgan or Albert Facey, there is not a great deal here which transcends

the personal. Clearly this strand offers plentiful material for poems

(as seen already in Croggon’s outstanding first collection,

This is the Stone)

- or possibly

for an autobiographical novel along the lines of Kate

Jennings’ recent

book,

Snake

(also about the

unhappy marriage of an writer’s parents). As it stands,

however,

despite Croggon’s more than competent writing, this half of

the book is

finally disappointing.

This is particularly so in contrast to the other strand dealing with

the 1869 voyage. Here Croggon displays both lyricism and insight. In

the sections ‘Anaesthesia’ and

‘Adelaida’ she reports convincingly on

the psyche of her young mother of three in a marriage already turning

unhappy. In between a complaining letter to her brother and a cheerful

letter to her husband describing the same unbearable shipboard

situation we get a moving and poetic embodiment of what must surely

have been the feelings of such a woman at that time and how severely

she would have had to repress them. The quality of Croggon’s

prose

itself is additionally affecting since it reminds us of how much of the

woman’s own essence she has had to give up to fit the demands

of others

- and the fantasies about marital happiness which she has absorbed from

them. One paragraph is enough to get the flavour:

When

I was a virgin and whole the sea was different, it was a horse and I

was fearless. I was blown across its expanse without harm, I knew too

little to care who I was. Now I am small and timorous, a nose poking

out from the wainscot, a scurry of frills, a noise of yes. I put my

hand to the ladle and the crib and arrange the silver. How is it I

despise myself so much?

In another section of this 1869 narrative, the one called

‘Ananke’, we

are given a strong and stylishly colloquial monologue by a female

convict who has been savagely abused by her employers in England - and,

seemingly, by her father as well (whose influence she finds impossible

to escape and to whom the monologue is addressed). In the closing

sections of this strand, both equally well written, Croggon becomes

steadily more metaphysical and the story becomes a kind of reenactment,

almost in magic realism mode, of Coleridge’s ‘Rime

of the Ancient

Mariner’. As a piece of prose the final section is,as the

publishers

claim, a

tour de force

but

whether it makes a convincing conclusion to the plot is another

question. As a postmodern appropriation, however, it is certainly

carried off with great élan.

It is hard, ultimately, to know what to make of

Navigatio.What do

you say when a

book is two books - one decidedly more than the other? Probably both

could have done with a little more work - the autobiography given a

little more of the poetic writing found in the other half - and the sea

voyage filled out perhaps into the full-blown lyrical and freestanding

novel that it wants to be. In the meantime Black Pepper has Alison

Croggon’s second volume of poetry well on the way, a book

which will

surely be less problematic and more consistently enjoyable than the

rather strange adjacencies of

Navigatio.

Back to top

New

Writing

Navigatio

Helen Horton

Imago, Vol.

9, No. 1, Autumn

1997

This is classed as a novel, but most of it is drawn from an

autobiographical source, even that half that is written as a fictional

account of a nineteenth century migration from England to Australia.

Except for two, the chapters alternate between this fictional family

and the writer’s own family, with its migration from South

Africa. The

exceptions are Chapter VIII, named ‘Angel’, a

series of fragments with

a dream-like quality, and the last chapter. In this ‘The Tale

of the

Ancient Mariner’ is retold via the medium of the log-book of

the

captain of a ship, the name of which,

Fidelis,

is symbolic, as is the ending of the book.

The focus throughout is on the far-reaching and complicated emotions

that are involved when a husband and wife relationship breaks down and

the inevitable spilling over into the minds and emotions of the

children, in this case, three girls.

This is not a story told sequentially. The chapters are individual

fragments, with the present and memories of the past constantly

intermixed, and firmly linked by the parallel family device. The result

is at times slightly confusing, but the book never wavers from its main

recurring theme of the emotional impact of family members upon each

other and their lasting effects. In the process of this emotional

probing, there is a certain amount of philosophising, that could

perhaps become just a little wearing. It takes the form, however, of a

questioning, rather than being didactic, and the reader is never

allowed to lose sight of the concept contained in the third paragraph

of the Prologue: ‘I want to migrate forever from these

shadowlands

where speaking is not possible because the darkness swallows every

syllable before it can be uttered, this realm that ate up my parents.

Each step takes me further into shadow, into the impossibility of

speaking. But I must persist.’ That tone is maintained

throughout.

Back to top

Books

Extra

Paperbacks

Navigatio

Fiona Capp

The Age, 30

November 1996

Established last year, Black Pepper is a small press which is rapidly

making a name for itself and has already published 16 titles. Alison

Croggon is best known as a poet, librettist and playwright. In her

first novel, she combines personal memoir with the story of a

19th-century sea voyage as she navigates the stormy waters of her

family’s past. ‘It took until my adulthood to

acknowledge how my father

lied to me... I don’t know how to navigate past what he has

taught me

about truth - that truth does not exist, that trust is

impossible.’

Now, as she contemplates the world her children inhabit, Croggon offers

up a meditation on memory and the meaning of

‘truth’.

Back to top

shorts

Navigatio

Airlie Lawson

Australian Book Review,

No. 186, November 1996

Find a comfy chair and a quiet room before you embark on

Navigatio. Though

slim, Alison

Croggon’s first novel is not light. Prose narrative overlaps

poetry to

produce a work densely packed with images and voices. The past, the

present and the imagination are all invoked, making the reader

constantly reassess and reconsider what has gone before.

Croggon, widely known as a poet, mixes her own story of migrating with

others. One of these others is a young mother who is travelling to

Australia over a hundred years ago, and her feelings of melancholy,

loss and looking are strikingly similar to the author’s own.

What is to be trusted? Doubting God, Croggon and the characters ponder

on the life of language, the nature of beauty and the cruelty of man.

Who is to be known they ask, and how? Is a person’s fate

wholly tied up

in what has gone before? The awesome helplessness of just being borne

along by life is wonderfully evoked in the final chapter, the logbook

of a sea captain, dated 1869.

A thoughtful journey.

Back to top

Navigatio: a response

By

Daniel Keene, September 1996

I am very grateful for the opportunity to launch this book. It gives me a chance to respond to it, and after reading

Navigatio

I wanted to respond. I needed, somehow, to express the joy it evoked in

me, joy in its subtle craft and in its potent contents. A response can

only be a secondary thing, a dignified shadow at best, the dignity of

which is something borrowed from the primary source, the book itself.

Like all fine work, I think

Navigatio

invites response, as much as it invites emotion and thought. For me it

also invites humility, not only in the face of the skill it displays in

its construction and execution, but in the face of the emotional and

intellectual terrain it covers.

Navigatio is a book of a little over a hundred pages, but it is a vast and complex work.

In order to speak of this book I need to speak of Alchemy. Of common

Alchemies and profound ones. Of the marriage of opposites and of

affinities. Of the deceptions and the truths of magic. I need to

conjure the idea of transformation, of transmutation; of the changing

of one thing into another, of base elements into richer, more resonant

states. Of an exchange of energies between a life lived and life

imagined, and of the equality that can be made to exist between these

two things. I need to speak of the imaginative riches that reside in

memory and of the memories that can be inspired by imagination. I need

to speak of drama and the dramatic, of poetry and what it entails, of

what it so fiercely requires. And perhaps finally, or firstly, I need

to repeat an old riddle. Question: when is a door not a door? Answer:

when it is ajar. This simple riddle is founded on the tricks of

language, on the difference between the spoken and the written, on the

idea that language is not a set of fixed meanings but a living energy

that has meaning only in usage; it is a riddle created by the invention

that the transparencies of language allows.

The riddle, the conjuring trick, the Alchemical, the metaphor, language

itself: they are all are pure drama. The dramatic concerns itself with

change, with transformation; with the living presence of that

transformation, experienced as it occurs. We can so rarely experience

tranformation, moment by moment; it either happens too quickly or too

slowly for us to perceive completely; usually we can only reflect and

remember.

Navigatio invites us to

witness the Alchemy, the riddle, the drama of transformation. It

spreads before us the process and the outcome. The magician, the joker,

the alchemist, the dramatist, the poet, reveal themselves. It is,

finally, an act of revelation. A revelation that leaves mystery intact.

In other words, an act of magic.

The architecture of

Navigatio

is deceptively simple: alternating chapters of biography and fiction,

one framing and revealing the other as the book proceeds, this

alternation giving the book its strange and irresistable momentum. It

goes like this: a woman is writing about her life; her life as it is at

the moment of her writing of it and of her life as it was, her

childhood. She remembers. Her remembering is a journey she takes,

through herself, through regions both familiar and unknown. She asks

questions of her self and of those people she remembers, old questions

and new ones. But she is always drawn back to the present moment, to

the moment of writing, to the act of writing itself. And then she

begins to imagine. Other lives. Another time. These other lives she

imagines, this other time, are connected to her; through common

affinities, through synchronous events, through similar longings,

through familiar sufferings. She invents a parallel world, a

coexistence as real as her memories, as present as her present moment.

This is the method by which

Navigatio seeks and discovers its form as a novel.

It is a stringent and confident design. But there is also a prodigious freedom of composition in

Navigatio;

in each chapter ideas are mixed with anecdote, biography with pure

fiction, historical detail with fantasy; there are passages of joyfully

intoxicated improvisation, that in ignoring unity of action achieve

more complex and richer structures. The writer is inventing her own

rules. But the rules she invents are not random: they are calculated

and calibrated, drawing on her deep understanding of poetics, and they

are finally, as all rules should be, liberating. The book takes

exuberant flight. But its wings are not made of wax. They are made of

steel.

Navigatio is at once an act of

intelligence and invention and an overwhelmingly generous act of

biography. That it resolves these differing if connected energies is

remarkable, and is the book's achievement. In its pattern and execution

it enters areas unheard of in Australian literature. It is a fearless

book of remorse and absolution. It is a joyous book, joyous in the face

of truths that are difficult, at the end of a labour that has stretched

the boundaries of both fiction and biography, that in the end resolves

them into a form that both exposes and increases the mysteries and the

reality of imagination and memory.

There is an ancient saying: Memory is the mother of imagination. In

Navigatio

memory and imagination stand together and sing to us, and the harmony

they make is richly alive, as beautiful a music as you could wish to

hear, a poem like no other I have read. It is pure joy.

Back to top

Navigatio

Navigatio