Wayne Macauley’s novella tells the story of a failed

government-funded housing estate. Envisioned as a village of 1,000

people 50 kilometres north of Melbourne, potential residents are

offered incentives, such as the building of a highway and petrol

discounts, to relocate. But these promises never materialise and the

community dwindles to seven people. Stranded far from the city, the

remaining develop an informal commune increasingly isolated from the

outside world.

The novella (though billed as a novel) feels more like a bloated short

story in form and scope and Macauley’s tale spirals into an

absurdist surreality reminiscent of

-era

Peter Carey. The residents of the estate (pseudo-cleverly renamed

‘Ur’ because those are the only two remaining

letter of its

official name - the Outer Suburban Village Development Complex) square

off against vandals, government freeway builders, and the creation of

an adjacent garbage tip. Eventually two are driven to a

bushranger/guerilla insurgency that evokes Ned Kelly.

To Macauley’s credit, the plot remains bewitching and

ethereal,

lending a vaguely allegorical bent to the story, which seems to reflect

on Australia’s own settlement and antipodean isolation from

the

West, as well as the alienation of modern suburban living.

Unfortunately, the characters remain flat and unbelievable - and while

this may be the point, evoking ‘types’ rather than

rounded

characters, this approach often comes off as affected rather than

effective. Bram, the novel’s narrator, claims to be in love

with

Jodie, but she remains a secondary character and inexplicably

disappears from this short book for dozens of pages at a stretch -

despite his supposed infatuation. At other points, important

information is delivered after the fact (e.g., after cleaning a gunshot

wound, one character conveniently mentions her background as a nurse).

Macauley’s prose, though verbose enough to suggest an

intellectual narrator, is staid and uncomfortably ridden with cliches

(such as ‘ridden with cliches’).

The book’s nadir occurs when a character literally navigates

up a

sewage-drenched river in a barbed-wire canoe - a premise trying so hard

to be clever that it nearly cripples an otherwise enchanting story.

Still, the hallucinatory power of Macauley’s tale ultimately

manages to surmount these shortcomings. His novella remains ambitious

and experimental - and it succeeds more often than it fails. In an era

when many Australian novelists are playing it safe,

Macauley’s

literary gambits are refreshing even when they don’t pan out.

Most impressively-for a work that is consciously literary, intellectual

and experimental -

makes for a page-turning, accessible read. It is not a masterwork, nor

even an unqualified success, but its high aspirations and ability to

tackle multiple issues in a small space suggest that Wayne Macauley is

an ambitious talent worth watching.

Romana Koval interviews Wayne

Macauley

27 November 2005

Blueprints For A Barbed-Wire Canoe

Summary:

We’re up the creek without a paddle this week. Ramona is in

conversation with Wayne Macauley about his first novel

Blueprints For A Barbed-Wire

Canoe.

It’s about a failed suburban housing development. And while

the

story is firmly rooted in the complexities of contemporary urban

Australia, it also has the timeless feel of a fable or allegory to it.

The new housing estate promises its residents a marvellous lifestyle,

but what they end up getting is a life they could never have imagined.

It’s a bleak, funny, and utterly original take on the

Australian

dream of owning your own home and living a happy life.

Ramona Koval:

Hello, Ramona

Koval with you on ABC Radio National. This is Books and Writing, and

this week we’re all going up the creek in a barbed-wire

canoe.

Wayne Macauley is the bloke who’s taking us there.

He’s the

author of a book called

Blueprints

for a Barbed-Wire Canoe.

It’s his first novel, published by a relatively small

publisher,

Black Pepper, and unusually for a first novel it’s just gone

into

reprint. It has also now found its way onto the Victorian certificate

of education English curriculum reading list, and it’s a book

that’s firmly rooted in the complexities of contemporary

urban

Australia, but it also has the timeless feel of a fable or allegory to

it.

Blueprints for a

Barbed-Wire Canoe

is the story of a failed housing estate, an outer suburban development

in Melbourne that offers the people who go to live there affordable

housing, a village lifestyle and the promise of a fast freeway to the

city. But in reality the services and amenities never arrive.

Eventually only a few obstinate residents remain, feeling conned and

isolated. As Wayne Macauley writes of their situation, and

it’s a

strange but actually very apt way to put it; ‘We had no

mighty

river of a freeway to irrigate us, to give us cars and life.’

Wayne Macauley:

Yes, it’s

an odd metaphor, isn’t it, because it almost goes against the

grain. We’ve been trained to dislike freeways, but in fact,

yes,

that’s right, almost every outer suburban development is

totally

dependant on them. So if we were to look at a symbol that represented

what actually provides life, work, travel to an outer suburban housing

development, then the freeway is it.

Ramona Koval:

So these people were promised a freeway, and they were encouraged to

really go to a suburban utopia.

Wayne Macauley:

Yes,

you’re buying a home not a house, you’re buying a

life…it’s more the advertising that annoys me

about the

idea of utopia. I think it’s possible for people to dream

about

utopias, and I think dreaming about them is fine, but selling them as a

package is another thing entirely.

Ramona Koval:

So these citizens

who’ve bought here in the ‘outer suburban village

development complex’, as it’s called, and

they’re

expecting this freeway as a river, giving them cars and life, and they

suddenly realise that they have been really let go by the planners,

politicians, and it has turned into a suburban dystopia. It

doesn’t turn into that immediately but slowly, slowly, and it

starts with a smell. Tell me about the smell.

Wayne Macauley:

It’s the

smell of sewerage flowing into a creek from a pipe that was never

connected. As simple as that really; the smell, the first scent that

something may be wrong. I suppose the idea of the smell, of something

that’s on the nose, continues throughout the book, as also a

rubbish tip is then put nearby, to the residents’ horror, to

the

residents’ disbelief, and that smell also wafts across the

estate.

Ramona Koval:

Interestingly though, Bram, who’s... well, I guess in a sense

he’s the author of this, it’s his history...

Wayne Macauley:

He’s a narrator.

Ramona Koval:

He’s a

narrator, but he is writing, he’s trying to write a history,

and

he’s an archaeologist in a sense too because we meet him kind

of

at the end when he’s digging through the stuff and

he’s

finding artefacts and he’s telling us about those artefacts

and

how they got there. Why does he stay in his stinking house?

Wayne Macauley:

Initially

it’s because he’s staying there out of protest. He

believes, and most of the other residents do, that this can’t

be

true, that what has been promised will come, utopia will happen. But

then eventually I think there is a point at which the logic of that

disperses and there is something more strange and perhaps insane that

takes over.

Ramona Koval:

There’s

also a kind of Ned Kelly twist, there are some urban bush rangers that

get developed during the plot, and all sort of twists like that. But

it’s a kind of bleak book with amusing bits.

Wayne Macauley:

I love that. That’s very quotable.

Ramona Koval:

Did you mean it to be whimsical?

Wayne Macauley:

There’s a

certain element to myself that enjoys whimsy. Whimsy’s a bit

wet

for me but... humour, I can’t help it. Amusing bits, I

can’t help it. And of course there’s another side

of me

that is dark, troubled... not troubled but that worries about things a

lot. So I suppose it’s those two things coming together.

I’d have to say that some of my favourite bits are those bits

where, as a reader, I would say, ‘I don’t know what

I’m supposed to do. Am I supposed to laugh here or

not?’

And I love that moment where any art form takes you to that very

uncomfortable place where you know you want to laugh but

you’re

not sure whether you should be, given the circumstances. But in fact

that’s often where the best laughter comes from.

Ramona Koval:

In the suburbs,

and in fact in this particular suburban dystopia, the name of the

suburb is Ur, because it was... now what’s the phrase again?

Wayne Macauley:

Outer suburban

village development complex. However, all the letters from the sign

which, on the roadway into the estate, have fallen off or been

souvenired by the vandals, and after some time everything except the

two letters from ‘suburban’ are left;

‘ur’, Ur.

Ramona Koval:

Which is also,

strangely enough, the name of a ancient city. Tell me about Ur, and

tell me about the fragments of poems at the beginning of the book.

Wayne Macauley:

There’s

an epigraph at the beginning of the book which is from an ancient

Sumerian poem. Most of those Sumerian poems are hymns, laments,

threnodies... they mourn the loss, mostly in fact, of cities, and this

being an extract from a poem called ‘Lamentation for

Ur’, I

think it is. Ur is famous for a couple of things. Ur is in the

Mesopotamian Valley in present-day Iraq...

Ramona Koval:

And Abraham came from Ur too.

Wayne Macauley:

Correct, yes.

That’s one of the things that it is famous for. In a sense it

was

the place in which Monotheism began really, and those three great

religions then sprang from that. Judaic myth and legend tells the story

where Abraham one day had a fit with his old man Terach who was a maker

of idols, and said, ‘You’re making all these idols

to all

these gods, this is bullshit, you know? There’s only one

God,’ and he actually picked up all the idols and smashed

them on

the floor. That’s what I think of your polytheism, Dad! And

off

he went and ended up, of course, going to the Promised Land as we know

it in that particular strand of mythology.

Ur was also an extraordinary place because it was also generally

acknowledged as the birth of civilisation. That is to say, some of the

fundamental things started there, particularly urban living. People

moved in off the plains and actually settled down, built houses, brick

houses, and they planted crops, they actually settled, and they

established all those kinds of city things that we know about. They had

pubs and cafes and stuff and they started to live an urban existence.

Also writing as we know it (symbols that imitate the phonetics of

speech) was invented in a.... which I find really intriguing, but

that’s where writing, as we westerners understand it, began.

And also probably the most important thing of all; beer was invented in

Ur. So Ur was a very interesting place, but of course as it relates to

this book clearly there’s a couple of things... one is the

idea

of an ancient civilization, an original civilisation, and from my

nihilistic view of how in some ways the civilisation of the west since

then has got so messed up and so screwed up. There is some sense of;

what is civilisation? Civilisation of cities, urban civilisations; how

can we be getting it so horribly wrong?

Ramona Koval:

But then again,

how can we expect that anything will last forever, because things have

always diminished after they’ve been built up.

Wayne Macauley:

Look, true, and

in some ways that’s the metaphor running back to ancient Ur,

which is precisely that; it rose and it fell, it rose and it fell, and

that’s what civilisations do. The other interesting thing is

archaeology because we only know about these civilisations by digging

them over...

Ramona Koval:

Through their rubbish dumps.

Wayne Macauley:

Well,

that’s absolutely true; we actually dig over their rubbish,

and

we pull them out and these things are precious items that we display in

glass cases in museums, and it’s what tells us about those

civilisations. So in some sort of small way, the metaphor of all the

letters but ‘ur’ falling off the sign out the front

of the

estate points us in this direction of an attempt at civilisation, an

attempt at urban living that unfortunately does go wrong and is

lamented over. But there are signs and symbols there, there is debris

embedded in the ground that we can go back and we can hunt though and

look through. As readers we can hunt through and look through the clues

and signs in this thing called a book. We can go back, dig that over,

have a look in there and see what we can find out about these people;

who they were, how they lived their life, and also maybe where they

went wrong. What happened? Why? Did they screw it up or were they

sacked by invaders or...? For me that’s the perhaps tenuous

thread between some place that rose up out of the desert, out of the

flat landscape 4000 years ago and an estate in some time roughly

concurrent with ours that springs up on the northern plains out of

Melbourne.

Ramona Koval:

Blueprint for a

Barbed-Wire Canoe,

this story of an urban nightmare, begins with days of pelting rain and

the discovery of the washed-up remnants of a canoe and the body of a

young woman called Jodie. Later, the narrator Bram is given a leather

satchel. Inside is a piece of writing that gives the novel its title.

Here’s Wayne Macauley reading what his character, Bram, has

discovered in the satchel:

Wayne Macauley

[reading from

Blueprints

for a Barbed-Wire Canoe, pgs 104-106]:

Be

sure you’re sick of life, say to yourself: I’ve had

enough.

Take a roll of rusted barbed-wire and some pieces of nail-infested wood

and shape it into a canoe. Choose a moonless night, a night with no

moon, the darkest night; you are the only witness, the only one who

should see.Take your canoe down to the filthy creek when the stench is

at its worst, tighten the chin strap of your hat and button your jacket

up hard—the journey will be long and fraught with danger. You

will use no paddle, you will need no paddle, but will carry a big jar

of salt with you and throw handfuls from the stern. This will propel

the canoe away from the dark unfathomable ocean, of which the salt is a

cruel reminder, upstream towards the pure crystal waters at the source.

Recite the prayer: Nothing Matters, I Don’t

Care—three

times every hour: this will give you strength. Hold your head up high.

Never doub tthe wisdom of your journey, do not ask Where or Why; the

canoe is a sensitive one, it may turn on a pinhead and rush you back to

the ocean or drop like a stone beneath you. All night you will travel

and well into the following day. When the salt runs out do not despair,

the waters will be clearing now and the canoe will know it has safely

left the muck behind. Dip the empty jar over the side and hold the

contents up to the light; you are looking for water so clear that it

seems not to be there, that the jar itself appears to dissolve in your

hand. If you do not find it onthe second day, do not despair, go on, if

you do not find it on the third, repeat the prayer more often and hold

your head a little higher. If you do not find it on the fourth or

fifth, don’t worry, go on. If after a week the jar does not

dissolve and the water in it is still putrid and thick, take heart, go

on, the second week may yet see you safely to your journey’s

end.

When in the third week the canoe starts leaking, bail it out, be brave,

go on, and when in the fourth week you find yourself becalmed and feel

it slowly sinking beneath you, bail harder, keep faith, don’t

worry, go on. It is then, and only then, as your carefully thought out

and well-constructed vessel sinks slowly towards the muddy bottom that

you may allow yourself to cry out: Help! But do it softly,

don’t

make a big show of it, you are the only witness, the night is moonless

again and you are miles away from home; do it softly, sweetly, and as

the waters engulf you don’t whatever you do forget to keep

your

head held high.

Ramona Koval:

So the way you

read that, of course, there is a bit of whimsy in that too, and then

you say, ‘don’t forget to keep your head held

high’,

but actually that is when the person is actually drowning,

isn’t

it?

Wayne Macauley:

Yes.

Ramona Koval:

And it’s a

kind of ‘never give up’, ‘keep your head

held high,

no matter what’s happening to you, don’t lose your

dignity’... but this is a suicide not.

Wayne Macauley:

Yes, it could

be thought of as that, but it’s also in some ways a summation

of

the thread that runs through the book which is precisely that. Maybe

it’s a little folksy and homespun but, yes, keep trying,

things

might get better, if not today maybe tomorrow. And that’s, in

fact, the core of belief amongst, I must say, these very ordinary

people who go to this place with a dream. So it’s not

unreasonable for them to keep hanging on to the dream, and really the

blueprints, as articulated in the book, the blueprints for a

barbed-wire canoe are in some ways a statement of fact of how these

residents have lived their lives.

Ramona Koval:

But then it

starts saying, ‘Be sure you’re sick of life. Say to

yourself, I’ve had enough, and then take a roll of rusted

barbed-wire and some pieces of nail-infested wood and shape it into a

canoe.’ I mean, that’s the suicide bit, I think.

Wayne Macauley:

I don’t know, I’m not going to necessarily agree

that is a suicide note.

Ramona Koval:

It’s a recipe for suicide.

Wayne Macauley:

Well, life is a

progression from birth to death and in that sense it’s one

long

walk to suicide if you want to think of it like that. I actually think

those blueprints are more (in that sense) philosophical. The

saying—to be up shit creek in a barbed-wire canoe without a

paddle—is something that I think expresses…what is

it?

It’s a way of saying how dreadful life can be, how appalling

the

situation is, whatever, but ah whatever, you know? I’ll go

on,

I’ll keep going. So it’s a fine line, as you say,

between

darkness and humour. But I don’t know if it’s a

suicide

note.

Ramona Koval:

I suppose I

thought that because we see this woman getting quite dead in the

beginning of the book from following exactly this blueprint.

Wayne Macauley:

It’s true

that the canoe doesn’t work and that’s a fact, that

you

can’t actually sail upstream, up a creek...

Ramona Koval:

With a jar of salt.

Wayne Macauley:

Even with a jar

of salt. You can’t, you’re not going to make it.

But,

again, the philosophy expressed in that, and perhaps again in the book

as a whole amongst these ordinary people, is that should that stop you

from trying? If you start from nihilism it’s all up from

there,

you know? I guess that’s, to some extent, what

we’re

talking about.

Ramona Koval:

The book is going

to have a young readership now. It’s been set for the

2006/2007

Victorian certificate of education English and English as a second

language curriculum, which is marvellous for you.

Wayne Macauley:

It’s

fantastic, it’s great, for two reasons; one is that

it’s a

first novel, so that’s obviously a nice pat on the back, but

also

it’s by a small publisher, Black Pepper, who are a small

independent publisher in Melbourne. So on both counts I think

it’s a real statement of faith...

Ramona Koval:

About nihilism?

Wayne Macauley:

And humour. Nihilism and humour.

Ramona Koval:

What do you think young people will make of it?

Wayne Macauley:

I look forward

to finding out. I mean that really sincerely. I’m excited

about

that idea. I do think it’s a book that will stand up to more

than

one reading, and I guess that’s one of the reasons why

it’s

been selected, that there are a lot of things to think about in there,

contrary perhaps to the picture you were

painting—it’s not

all bleak because it’s leavened by humour a lot and also some

characters that I think you can emphasise with. So, again, those things

are attractive to people who are perhaps engaging with literature for

the first time. I think the main thing is that it feels that

it’s

got stuff to say and be discussed, which is a great thing to know that

your book will be talked about. It’s also a great thing to

know

that your book will be talked about (perhaps hated, who knows, it

doesn’t matter) by people at that very formative point in

their

lives, because I can remember that moment.

Ramona Koval:

Oh yes, and bleakness or nihilism or passion or... it’s all

very much part of the make up...

Wayne Macauley:

It’s all

that moment of time and I remember that time vividly, and it shapes you

as a human being, no question, those years. So, look, I think

it’s a great privilege to have your work read by people of

that

age and discussed by people of that age and argued with or whatever the

case may be. It’s a wonderful thing.

Ramona Koval:

What sort of a young person were you?

Wayne Macauley:

I was a bit rebellious and I kind of took a while to get my head

straightened out.

Ramona Koval:

Where were you living?

Wayne Macauley:

I was living

out in the outer eastern suburbs of Melbourne, Mitcham, just the burbs.

But I had that epiphany that everyone has to have, and it was HSC (as

it was then), year 12, and I chose to do English literature and this

drop-dead gorgeous teacher walked into the room. We did Joyce, we did

Hamlet, we did

Voss, we did

Eliot’s

The

Waste Land... bang! It all went off in my head, and I was

a changed man. I was a man.

Ramona Koval:

She made a man of you.

Wayne Macauley:

Yes, that was

really the moment where I discovered what writing was, what you could

do with it, why it was there and how it could just blow your mind

compared to the thrashing around I was doing. Something went clunk in

my head.

Ramona Koval:

And then what happened?

Wayne Macauley:

Then I left

school and worked on a market garden, and I saved some money and I

travelled around Europe. Then I came back and I did a year at

university, which was good, and then I applied to go to a drama school

too, the Victorian College of the Arts drama school... out of nowhere.

I saw an ad in the paper and saw ‘arts’, and

extraordinarily I got in. I was in my early 20s. I went to drama

school, dropped out of that too, travelled, wrote, travelled, wrote...

and at some point, when people asked me what I did, I started saying

‘writer’. And it takes a long time to arrive at

that point.

No matter how long you’ve been doing it, it actually takes a

long

time and it is a statement of faith. It’s a moment where you

(even if you don’t have a lot of work out there) say

‘this

is what I do’. I guess that is who I am.

Ramona Koval:

What had you written then, when you were calling yourself a writer?

Were you published by then?

Wayne Macauley:

No, I

hadn’t been published. I’d been writing for theatre

and

that was initially what I was doing. I was writing for theatre and

having it performed. I’d been writing short prose, stories,

none

of which I think I’d even tried to place. It was a very

internal

world I was working in. But then I guess it was not long after the

morning that I woke up (so to speak) and called myself a writer that,

yes, I did have my first story placed, and then had progressively stuff

that I had written previously and maybe reworked and worked on and

redrafted... then I began to have my stories published. Then I knew I

was writer... well, a writer of fiction anyway.

Ramona Koval:

The book is dedicated... it’s for your father

‘as promised’. What was that promise?

Wayne Macauley:

It’s

emotionally complex. It’s a promise as much to myself as

anything, but partly to him as well. My dad died quite young. In fact

my dad died the same age I am now, which is 47, which I consider quite

young because I am 47. That was around that upheaval time, really, that

we were talking about before; I was 20 when he died, so I was only just

discovering this thing called literature, you know? And he passed away,

and I don’t think he knew what the hell I was on about, what

on

Earth I was doing with my life...

Ramona Koval:

What did he do?

Wayne Macauley:

He was a

builder. He worked on big building sites in the city, and contracted

early-onset emphysema which was actually related to his work, breathing

the stuff. So he was sick for a long time, not a well man for a long

time. So obviously, me having seen the drop-dead gorgeous literature

teacher and had my epiphany, we were obviously going in separate paths

at that time. So obviously that, as I’m sure it does for a

lot of

people who lose their parents young... it stayed with me and affected

me in many ways. I know that progressively over those lost years,

before I called myself a writer, that I was trying to work that stuff

out. So I knew that one day I would have a book published and that when

I finally did it would be dedicated to him.

Ramona Koval:

There’s a lot of building in this book actually.

There’s a lot of building, there’s a lot of

constructing.

Wayne Macauley:

There’s a

lot of building in my work generally, as a couple of people have

pointed out recently. So, yes, how much of that is conscious I

don’t know, and how much is subconscious. Yes, there is,

that’s right, and the idea of the house, the home, the great

Australian dream... my dad... actually his dad too was a builder and

they built our house, the house I was born in and brought up in, out

there on the edge of the known universe. So that also is something that

runs very strongly in what I do and who I am, but also how I see myself

in this place. Somehow that strange collusion between my father, what

he did, his death, me becoming a writer, being an Australian, being a

Melbournian even more so, all those things somehow are coming together

in my work. I guess they have come together in

Blueprints for a Barbed-Wire

Canoe

in that sense because it’s about the great Australian dream,

building your house on a block of land and living a happy life.

Ramona Koval:

Wayne Macauley. And

Blueprints

for a Barbed-Wire Canoe, his first novel, is published by

Black Pepper. And another novel by Wayne called

Caravan

Story will come out early next year.

That’s Books and Writing for now, which is produced by me,

Ramona Koval, and Amanda Smith.

Back to top

Author

Notes on Blueprints

for a Barbed-Wire Canoe

Delivered at the 2005 VATE Conference

EXCAVATING UR

It

had rained for three days solid, in some places the creek had already

burst its banks; she’d waited for nightfall, a night with no

moon. No-one

can say

how spectacularly unsuccessful the launching was, no-one was there on

that dark night to bear witness. Though the remnants of the canoe were

found the following day wrapped crazily around an overhanging branch

almost a kilometre downstream, there is little point speculating on how

much of the journey was made on the surface as hoped and how much of it

tumbling in the putrid waters beneath. The body itself outdistanced the

canoe by a kilometre and a half and was recovered two days later wedged

between the root of a tree and the grey mud of the bank. It wore,

ridiculously, the uniform prescribed; the rabbit skin hat still held in

place by a chin-strap, the jacket still neatly buttoned.

I was asked into town to sign some papers and I drove there dazed and

shaken. Patterson himself seemed genuinely upset. It was, we both knew,

a strange and futile end to a strange and futile saga. Little was said,

little could be said; I saw the body, identified her as Jodie and drove

back home with the image of her blood-drained face and quiet

closed-forever eyes before me.

The rain wouldn’t stop, it came down in endless thin silver

ropes,

pelting the roof and bursting out of the gutters; it was washing

everything, washing everything clean, the whole sad sorry story, across

the paddocks and ruins, from trickles to rivulets to the creek into the

far-off sea. That night, as I sat down at my table and prepared to

break the news to Michael, I knew, at last, that my days here were done.

Michael! Mad, bad, cockeyed Michael! That it should all come to this!

All the twisted lines of our journey, the scratches, the cuts, the

bruises, were marked on her face. But serene, so serene, ghost-white

and pure. Michael! Oh Michael! That it should all come to this!

~

I

loaded the car up with beer from the pub in town and pulled the table

up that night to within arm’s reach of the fridge. Empty cans

littered

the table, the rain drummed hard on the roof. Hours passed, they could

have been years. I couldn’t write to Michael, there were no

words to

fix the image, wrap it in sympathy and carry it safely to him: six

screwed up pieces of paper lay strewn across the floor. I raised myself

unsteadily from the table, stood at the back door and looked out at the

rain. It had already washed the gravel from the path leading down the

back to the creek and the paddocks beyond lay shrouded in darkness and

damp. She’d have passed by here, just down there at the end

of the

path, beyond the murky shaft of light, where I could hear the sound of

the boiling, rushing water even now. Was she standing, head held high

as instructed, or already tumbling, groping, lost? I’d have

been

sleeping, the rain on the roof. And she passed by softly: I

couldn’t

have heard.

I put on my coat, took up the lamp, and walked out into the rain. I

made my way down North Court and trudged to the top of the mountain of

rubble that overlooked the Square. It was a lake now, a low lake of

muddy water in which a few persistent gorse bushes still stood. Nothing

to suggest the summer evenings of suffused orange light, the clinking

of glasses and the hubbub of talk; those long magical evenings now a

lifetime away. Grey sky, grey mud, grey water, drenched by an unending

rain. I walked down the eastern side of the hill towards the few houses

that still stood, miraculously, north-east of the Square. My boots were

caked with mud, my steps were leaden. Thick weeds, gorse and thistle

had long ago claimed the streets; they slapped at my thighs, tore at my

flesh and wet my trousers through.

I walked into the lounge room of an empty house; it reeked of dogs,

bird droppings and damp. A bird flew out the window, leaving the echo

of its flapping in the room. I remembered Michael, and our meeting in

the abandoned house on West Court all those years ago. Flies buzzed in

zigzag patterns around the broken light fitting and the dogs stretched

and yawned on the burnt-brown lawn. That summer was the worst, the

paddocks around us were dead grass and dust; the streets melted, the

gardens withered, a heat shimmer wobbled and distorted everything in

the middle distance and beyond. Days on end spent waiting for night,

nights on end spent dreading the days, we cowed beneath an open sky,

hugging the walls and shadows, listening with one ear cocked to the

distant rumblings whose source we could still not name. He was her

father, I was in love with her, all my words were servant to these

truths.

I trudged back home, my boots and the shoulders of my coat soaked

through, and lit a fire in the grate. Steam rose from the boots on the

hearth and the coat flung over the chair: it hung below the ceiling

like a cloud threatening rain. Rain, rain, everywhere the rain. It

battered the roof and dripped with an insistent rhythm into the

saucepans. I sat at the table and gazed again at the objects assembled

there: a piece of glass from a broken beer bottle, a chipped house

brick, a charred rabbit bone. I arranged and rearranged them on the

table before me, imploring them to tell a story, to reconstitute

themselves into a whole. But they remained stubbornly themselves;

inert, mute, adrift. So are these few reliquiae all that I have

salvaged from the ruins of those years? Small things, absurd,

earth-encrusted things. Had I not come back to dig them out they would

still be sleeping peacefully where they should be, in the all-forgiving

earth.

[pgs 1-4]

It is a great privilege to have your book listed as a text for study,

particularly if it’s the first book you’ve had

published. It says, I think, that your book is considered worthy of

being looked at more than once. And that for me is what a good book is

all about. The books

I

like, anyway. They ask to be read again. They

say to you: I’m more than just surface, there are layers here

too.

Blueprints for a Barbed-Wire Canoe is a work of irony, and

as such, I

think, it can stand a bit of archaeological excavation. But that

doesn’t mean that what’s beneath the surface is

going to be easily read. I don’t think that’s what

literature’s about: a book should get you thinking, but it

shouldn’t tell you what to think. Fiction-making is a

speculative enterprise, and it’s in these imaginative spaces

the speculative enterprise opens up that the real pleasure of

storytelling and story-reading can be found.

My story is set in the barren cow paddocks to the north of Melbourne,

familiar to us all, but it is also set in ancient Sumeria, in the

fertile delta between the Tigris and the Euphrates. By that I

don’t mean that I jump back and forth between these two

places, as some more cosmopolitan globe-hopping authors might; no, my

story takes place exclusively on the plains north of Melbourne but

beneath it, as subtext (to use the old term), lie those other more

fertile plains of ancient Mesopotamia.

In the Mesopotamian valley, between about 3000 and 2000 BC, some

amazing things started to happen. Nomadic tribes started to, as they

say, ‘settle down’; and the idea of a house, a

home, was born. Why wander the desert looking for food when you can

grow it - grains especially - in the fertile soil of the delta? People

started grabbing blocks of land and putting solid brick houses up on

them. They dropped by to meet their new neighbours. They became a civic

community. Writing was born - yes, writing as we now understand it, the

permanent marking down of symbols to imitate the phonetics of speech -

and, soon outgrowing its purely market-driven origins, this writing

started to convey not just recorded facts but possibilities too and not

just thoughts but feelings. We find poems and stories (the Epic of

Gilgamesh is one), hymns and laments, that, once part of an oral

tradition, were now part of a written tradition too. And all this

activity - drinking, thinking (the Sumerians invented beer too)...

drinking, thinking, despairing, writing - reached a peak around the

second millennium BC in one particular city in the Mesopotamian valley

called Ur.

And in this city called Ur - to keep ourselves in Mesopotamia for a

moment - around 2000 BC, something very significant happened, something

that would in due course drive a wedge between the Old World and the

New, and set Western civilisation in particular (if civilisation we can

still call it) on the path it is now on. Because in this city lived a

young man called Abraham, who, distressed and confused about all the

idol-worship going on around him - An the God of Heaven, Utu the God of

Sun, Enlil the God of Wind, Enki the God of Rivers, Nanna the Goddess

of Moon, Ishkur the God of Rain, Ninurta the God of Floods, Inanna the

Goddess of the Morning and Evening Stars - one day heard the voice of a

new monotheistic God talking to him. Forget about all these other gods,

Abraham’s new God said, there is only one God now, and

that’s Me. Come away from all this confusing, primitive

polytheism and journey now to a place called Canaan, the

‘promised land’, which I have set aside for you.

We’ll start afresh, God said.

...and they went forth... [says Genesis] from Ur of the

Chaldees,

to go into the land of Canaan; and they came unto Haran, and dwelt

there...

The idea of a utopia, a promised land, runs deep through the Australian

psyche - the early explorers’ belief in the existence of an

Inland Sea, the events of Eureka and its secessionist subtext, wacky

young Ned’s Kelly Country Republic. And what has undoubtedly

fed into all these utopian dreams is the idea of Australia - Terra

Australis, Terra Nullius - as herself a Utopia. From the picture

painted by the ancient Greeks of Antipodean giants sitting under their

umbrella feet drinking Vodka Cruisers in the sun, to the Ramsay Street

of

Neighbours,

‘promised land’ utopianism has

always clung to us like a green and gold lycra body suit. We represent

Hope with a capital ‘h’: in hope people come here,

in hope people live here. We are western civilisation’s dream

home, the one down the end of the street upon which the sun is always

shining and in the window of which fresh smiling faces can always be

seen. In us and only in us rests the possibility of creating western

civilisation anew, of avoiding the screw-ups, of getting it right...

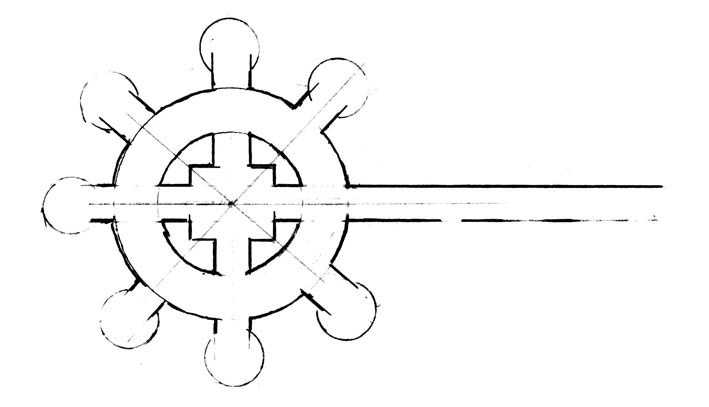

The Estate was built in

record time and the official opening was

attended by many dignitaries, the most important of whom, the Premier

no less, unveiled the small bronze plaque that up until the destruction

still stood on the grass plantation in the centre of the Square. It was

all a cause for great civic pride at the time and those of us who were

there, the first residents, guinea pigs if you like, felt that we were

taking part in an event of great national importance. Speeches were

made, a large marquee covered the Square and beer, wine and savouries

were served. I hope, said the Premier, one hand on the podium to

prevent his speech being carried off by the wind, that this will become

the model of things to come.

And yes, despite its questionable location and the hurry to completion,

despite everything that has happened since, the Estate was a model of

the new planning ideas at the time and was, in its way, absolutely

unique. It was designed as a kind of self-contained village; a main

Square in the centre surrounded by shops, a bank, a post office and so

on, with four streets radiating out from this Square to each point of

the compass. Each of these four streets then crossed a ring road some

forty metres out from the Square with all except one terminating on the

other side in three bubble-shaped cul-de-sacs or courts. The fourth or

eastbound street crossed the ring road and continued on for a little

over a kilometre until it met up with the main highway to the city -

the only access, by road, to the Estate. Four further cul-de-sacs or

courts branched off from the ring road, making seven in all.

So that the whole thing resembled, if seen from the air and with a

touch of imagination, the great wheel of an old sailing ship bound for

exotic new lands. The four streets and seven courts were named

according to their corresponding positions on the compass; North

Street, East Street, North Court, North-East Court etc.... And they

all, including the ring road, were lined with houses - two hundred and

twenty in all and all identical in design: three bedroom solid brick

with front yard, back yard, driveway and garage. On the basis of four

and a half persons per household, the designers had calculated on a

population of nine hundred and ninety people.

It was, to anyone’s way of seeing things, an extraordinary

achievement.

[pgs 7-9]

My book is set on those flat basalt plains north of Melbourne, where

the last scraps of the outer suburbs tumble over into overworked,

weed-infested cow paddocks. It’s the place ‘in

between’, the most interesting place when you think about it;

a place of ‘possibility’. It is neither city nor

country, urban nor rural. It’s the paddocks north of

Craigieburn, the flatlands out the back of Melton, the Western Highway

past Caroline Springs. It is a place of hope, of new possibilities - in

a world supposedly of no new frontiers it is just that: the new

frontier. Every day another pioneering family loads the wagon and heads

out there. They carve out their quarter-acreage and put up their

dwellings: frontier outposts in a hard inhospitable landscape. They put

up fences and within them set about cultivating, taming, civilising,

the landscape. Instant turf, a weeping cherry, a passionfruit vine

along the back fence. They make a ‘home’ for

themselves (these are not ‘houses’, these are

homes) and

prepare to raise children in them.

I come from the outer suburbs, and have always had an ambivalent

relationship to them. On the one hand I find them absolutely

stultifying, mind-numbing, awful, and on the other the idea of the

suburbs as a

tabula rasa

-

possibility

as opposed to

actuality

- is the

premise that underpins almost everything I do as a writer. For me they

represent the true essence of this country’s white settler

culture (the only culture I have any real familiarity with): a culture

built on our absolute, even irrational, belief in freedom, opportunity

and prosperity. It is the

landscape

of possibility.

The suburbs are and always have been this country’s political

barometer, whether we like it or not what goes on out there (out

here)

shapes our politics in ways we often have trouble dealing with. The

last two federal elections were fought and won in the so-called

‘mortgage belt’ where the twin threats of interest

rate rises and invading foreigners delivered everything that could be

asked of them. It’s in the suburbs that this kind of stuff

bites hard, because it’s in the suburbs that our grandest

utopian dreams are played out. The politicians know the suburbs are

where it’s at. I wonder if the reason so much of our art is

so out of touch with our politics is that our artists are too

embarrassed to admit that our policitians may be right. It seems

we’d prefer to live, both actually and imaginatively, in some

eucalypt-scented bush, some revved-up translatlantic metropolis, some

Tuscany - or in the past. But not in those wide streets, those

well-fitted houses, those shopping centres, those arterial roads. There

is a constant imaginative flight from the suburbs, as if it were a

place unworthy of us.

Is

it? Or is it actually

who

we are?

Outer Suburban Village

Development Complex the sign on the access road had read,

but over the years all but the letters ‘ur’ from Suburban had either

fallen off or been souvenired by the vandals. In time to come we would

take this name - ur,

a kind of laconic mumble - as our own and keep it as our own private

joke, but either way, both then and later, the name remained hidden

from everyone but us. We had never appeared on a map under any name,

old or new; the cartographers had barely begun to sketch us in before

they were forced to erase us again. The dilapidated sign out on the

access road was all we had to call attention to our existence and rare

now, if ever, were the times when foreign eyes fell upon it.

Occasionally, on a weekend stroll, one of us might see a car pull up

out on the access road and a poorly-dressed family stand gazing for a

while at the strange collection of houses in front of them. But if they

had come to consider the idea of moving into the Estate then the idea

quickly deserted them. The family dog that had scampered down to the

ring road corner to sniff the tails of the others who had gathered

there to greet it was quickly whistled back and leashed and the family

got in and drove away, carrying with them the first chapter of the

story they would tell to other poorly-dressed families back in the

city, a story that would end with the words: No, don’t

bother,

we’ve seen it and it stinks.

It did stink. Though the sewage produced by a mere seven individuals

may be rightly considered a trifle, it was more than enough to infect

the slow-moving creek and the market garden with a rich rotting smell

that often and particularly in summer hung over the northern part of ur like a poisonous

cloud.

[pgs 25-26]

When I was in Form 5 at Vermont High School I wrote an English

assignment, since lost, that must have revealed the first stirrings of

the piss-taking poetic satirist in me. I can’t exactly

remember what I wrote, I’m sure I was just being a

smart-arse, but, after giving me an ‘F’, my English

teacher, Mrs Whitrod, suggested I read something called ‘A

Modest Proposal’ by Jonathan Swift. I didn’t, of

course, I was a smart-arse. But years later, secretly, I took up her

suggestion and when I did I realised why. She was suggesting that even

this rebellious, aggressive sixteen year old energy, this cynicism,

this facetiousness, that even this, of all things, could be turned into

art.

I’m sure you’re familiar with the work Mrs Whitrod

was referring me to but I’ll quickly revisit it anyway.

‘A Modest Proposal’ was written in 1729 by Swift,

an Irishman, at a time when the ‘Irish Question’

was being hotly debated in the English parliament. A lot of high-minded

speeches were being made, and paternal suggestions put, about how to

deal with the poverty and overpopulation of Catholic Ireland. Swift, in

the guise of a public-spirited citizen, offers his ‘modest

proposal’ - that many if not all of Ireland’s

problems could be ameliorated if the babies of poor Irish parents were

sold as table meat to the rich. It is a brilliant proposal, brilliantly

argued. It walks that fine line between the believable and the

outrageous in a way that still makes me envious. It is a satire of the

highest order. Swift - and this is the essence of it - is not talking

as Swift, Swift doesn’t seriously think we should sell our

babies for table meat, Swift is taking on a character, he is

‘impersonating’ someone (from the root

‘persona’), he is an actor speaking with a

character’s voice, he is trying something on, he is doing a

‘what if?’. He’s finding a way, an

artistic way, to use all his, Swift’s, anger, cynicism, and

disgust. He’s being cool, rational, reasonable, logical. He

is - and this is my point - putting the reader in a very difficult

position. Should we believe him? Do we take him seriously? Is this

meant to be fact or fiction...?

Shortly after, as the

first of the

autumn rains began sweeping in across the paddocks, Michael started

building the wall. I had neither the presence of mind nor the

wherewithal to stop him. He seconded Alex and his bulldozer (at the

point of a gun, as I later discovered) and had him knock down half a

dozen empty houses on the edge of South-East Court. He sorted the good

bricks from the rubble, ferried mud for mortar from the creek, and day

by day the wall grew higher. It rose on the outer edge of the ring

road, with the footpath for a foundation, and one by one over the

winter that followed all the houses outside its confines were

demolished to provide the bricks. Michael worked every day until the

light gave out, often in the drizzling rain, carting mud from the

western branch of the creek on a flat-topped barrow made from scraps of

wood and an old bicycle wheel and laying bricks with a home-made

trowel. A few of the others tried to talk him in - we feared for his

health above all - but Michael could not be swayed. The wall eventually

rose to thirty courses, over two metres high, and ur

was in the end contained exclusively within the confines of the old

ring road, its size reduced by more than half. As Alex’s

bulldozer bore down on the last house left standing in North Court I

resigned myself to the inevitable, packed up my things and moved to a

vacant house on the corner of North Street and the Square, diagonally

opposite Slug’s.

Closer to Jodie, I remember thinking, as if that were any consolation.

As winter drew to a close, Michael topped the wall with a tangle of

barbed-wire and broken bottles and constructed a huge barbed-wire gate

to stop up the access road entrance. With the first days of spring,

Vito began planting his new crop in the Square (he’d already

dug

up all the front lawns of West Street in preparation for his new system

of rotation): the last vegetables had been picked from the old farm and

it would now be abandoned. ur

had become, by a roundabout route, the village it had never been

before, and now within the confines of Michael’s wall its

security seemed assured. Some of my forebodings diminished; there was

still reason to hope. I cleaned out my new house and unpacked my

things. But then, like all the lights flickering in all the houses of a

vast suburb before the power fails completely, there followed a series

of otherwise unrelated events that could only be read as premonitory

signs of the great upheaval to come.

[pgs 50-52]

I said at the start that

Blueprints

was an ironic work. So what what

does that mean? Soren Kierkegaard, in his fabulous book,

The Concept of

Irony, said irony is ‘a nothingness which

consumes everything

and something which one can never catch hold of...’ Irony, he

was saying, is a slippery thing, hard to catch, is actually nothing, a

metaphysical space. I like to think of it as the space the author puts

between himself and his subject, a space then into which (a space,

again,

in between,

of

possibility)

the readers’ imagination

can be let loose. But Kierkegaard also said irony ‘is

something in its deepest root comical’. I think

that’s equally true. For all that I’ve been going

on about the things my book might be and might not be about, I should

remind you that in the end it is a essentially comedy, built on this

Kierkegaardian nothingness of irony. A writer takes on a persona,

through that persona invents a world, into that world invites a reader,

then asks that reader to engage in this invented world’s

dialectic. The essential ingredient of an ironic or satiric work is

that it can’t be judged by what it appears to be, or what it

appears to say. (Swift wasn’t

really

suggesting

the Irish eat

their children.) Irony’s about being

difficult, playing

games

with the reader, screwing with their expectations, undermining their

confidence in what something is ‘about’, landmining

their comfort zone. It shouldn’t create a settled world of

known, comfortable truths but a world built on speculative

what-ifs.

What if there was an Ur not only on the plains of ancient

Mesopotamia

but also on the paddocks north of Craigieburn? And what if there was

someone called ‘Bram’ living there? And what if he

was trying to write, to record this place’s goings-on? And

what if the kingdom of Ur fell, and there was a great rain and a great

flood? And what if after this great flood Bram left for another place,

a place in the West, a place where it would all become clear, where

he’d be told how to live, what living was for...?

The skies have cleared,

the lakes and

puddles out on the paddocks have drained away and dried, the creek

trickles past at the end of the garden, returned to its former size.

Though the fertile silt washed up all around looks like a

gardener’s dream, I haven’t bothered to re-plant my

vegetables nor do any of the things I had planned to do when the

weather finally cleared. The smell of the earth after so much rain is a

strange and intoxicating thing; I’ve been content most days

just

to stand at my door and draw it languorously into my nostrils. Since

the rain stopped and my story was finished I’ve done very

little

else, though I’ve managed to re-bury most of the junk

I’d

collected back in the hole in the hill. That took me a week, in a

slow-moving dream; I barely had the strength to lift the shovel. For

three days I anguished over what to do with the tangle of barbed-wire

in the corner; in the end I dumped it unceremoniously back into the

creek. Most of the things in the house are packed, my bundle of papers

snug in a cardboard box. Today I went to the top of the hill to take

one last look over old ur

and

saw the bulldozers trundling towards me in the distance. The freeway

was coming again. It will be a sharp turn to head west from here, I

thought, and in the years to come the drivers encountering it on their

way to Haranhope will mutter a low curse at such shoddy planning. And

yes, in the end old ur

will

perhaps only be remembered as a dangerous bend in the freeway north of

Melbourne, just where it crosses a dry creek bed before turning sharply

left towards the New Estate in the west. Patterson arrived in the

afternoon - his last benevolent gesture - to help tow my car from the

bog. I spent the remaining daylight hours packing the last of my

things. There was little to do then but sit and think - it’s

a

pleasant pastime, that. About Michael, Jodie, my neighbours, all gone,

and the sometimes silly things that happen in this life and that so

soon pass into the obscurity of history. It was only an experiment, I

thought, built too far out in the wrong direction, favoured or flawed

by its own possibility. Should someone dig it all up again one day

I’m sure they’d make a damn sight more sense of it

than me.

I had my bundle of papers, certainly, and some time, somewhere, on an

evening like this, they might bring me a little edification and take

the sting out of that day’s particular disillusionment. But I

would not be setting sail on them, hat on head and jar in hand. No,

that nonsense is over, my days here are done, tomorrow I leave for

Haranhope where a barrow of bricks lies waiting. This time

I’ll

start from the bottom up and see what comes of that.

[pgs 146-147]

Back to top

Blueprints

for

a Barbed-Wire Canoe

Blueprints

for

a Barbed-Wire Canoe